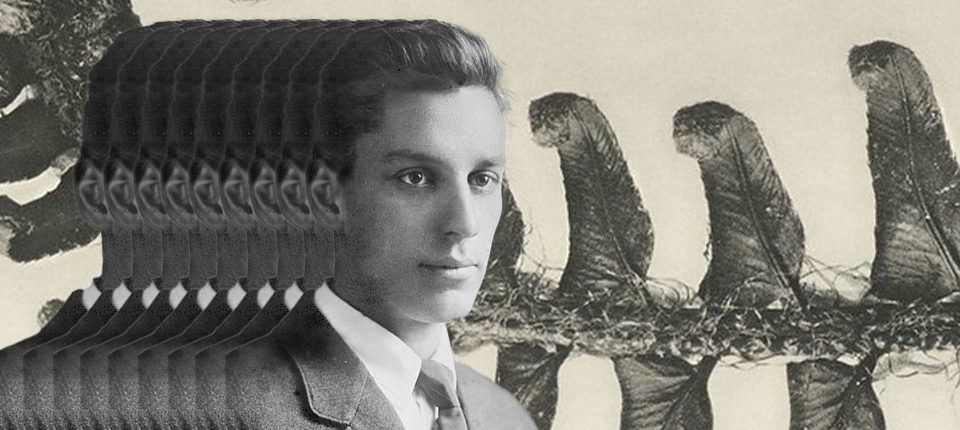

Chia-Lun Chang is one of the funniest and most serious people I know. Often, she’ll say something so profoundly grave with such good humor that I’ll belly laugh before grimacing. Chang is also far and away the most self-aware person I know. “why are you so serious,” asks the poem “The Milky Way” in her disarming debut collection, Prescribee. “The Milky Way” comprises about two dozen blunt questions, sans question marks—“are you confused about your nationality. can you read. how long have you been learning english”—which speak to a barbed awareness of how she may be perceived and approached.

Throughout Prescribee, Chang’s poems grapple with the extremes of hypervisibility and invisibility that can define the position of an immigrant in America. “I’ve been questioning / the difference between / disappearing and death,” says the speaker of “My Green Card Was Denied.” Fear of death pervades Prescribee, and the poems—seeking an antidote—become the antidote, because Chang won’t disappear now; her book is proof of life.

Zachary Pace: Would you describe your path to writing poems in English?

Chia-Lun Chang: I speak Mandarin in Taiwan, and when I was young, I had trouble learning the phonetic symbols, bopomofo. After I switched to writing with characters, language became my favorite subject. The unique system of the graph creates mysterious meanings with the characters and this allowed me to express myself in text. When I came to the States, I lost that sense of meaning, because I only had full access to the skill of my first language. (I also speak Taiwanese at home, but my family and I didn’t adopt a rigid written system.) I had studied English in Taiwan, and when I came here, I practiced seriously by taking writing classes.

Taiwan has one of the longest periods of martial law in history. When my parents were young, speaking Taiwanese was forbidden; they were punished with a fine. We now feel awkward and inappropriate when communicating in our native language. Growing up, the majority of the books I read were by Chinese authors. I didn’t know of any Taiwanese authors. So it felt impossible to become a writer. I might be a good secretary or a personal assistant, and that’s what I was raised to believe.

ZP: And what led you to pursue graduate studies in creative writing?

C-LC: It was mostly a financial decision. I’d always been interested in language, but my parents were strongly against my studying Mandarin literature as a major. In Taiwan, people who study Mandarin literature mostly become teachers. Since Taiwan has one of the lowest birth rates, more schools are shutting down, and teachers are having a hard time finding jobs. My parents insisted that I study business administration to be able to work for a corporation. So business administration was my major, but I was bad at it and scared to fail. I applied for a minor in teaching Mandarin as a second language. When I told my mom, she was upset—it was more popular to teach English as a second language. But I gave it a try and hoped I could thrive. The first job I had was teaching Mandarin in Vietnam. Then I came to the states through a small program and taught Mandarin at Tougaloo College, in Mississippi, and for the first time I was able to take courses that I was interested in. That’s where I took English literature and creative writing classes to practice the language. My parents couldn’t afford to pay tuition for graduate school in the States, but my creative writing teacher told me that in many MFA programs in the US, I can work as a TA and deduct tuition. So I decided to study creative writing. I went to LIU, and I paid around $300 per semester and worked as a TA.

ZP: Did you have any exposure to poetry before then?

C-LC: When I was in Mississippi, I didn’t enjoy poetry yet. It felt abstract. I didn’t have any sense of what a poem is. My first love, in English literature, is the play. I still remember, I read Harold Pinter’s Betrayal and was amazed by the concept of “time” in the language. Tense is one of the most difficult grammar rules for me because verbs don’t change forms in Mandarin. Plays were also easier for me to read, as an ESL reader. I took classes in fiction, nonfiction, playwriting, and poetry. But everything I wrote—maybe because my language has boundaries that make it difficult for people to access my expression—everyone would say, “This would be a good poem.” I didn’t grow up saying, “I want to become an English poet.” But poetry was the only space that accepted me for who I truly am—a work-in-progress human form—my language and artistic ability.

In the States, I’ve received some recognition, but peers in my hometown—my parents—don’t have any access to my creation. No matter how hard I work, my parents can’t fully comprehend what I’ve accomplished. My friends who write in English share the same longing, and their families have limited access to their experience, too. For my parents, even if they try, they can’t; the boundary is massive. I’m reborn as another person in a distanced language.

ZP: Your parents are recurring subjects in your poems. Does writing in English allow you to address aspects of their experience that you wouldn’t be able to address otherwise?

C-LC: Is this your question: Because they don’t have access to the language, does that give me more freedom to express, since I won’t piss them off? Even without the cultural differences, in America and Taiwan, our class—which is working class—is not a traditional topic. My mom is a factory worker, and my dad works in security. I see them as characters, and their story is important. I try my best to be objective. Their emotions are interesting to me—and so immense that it can be hard for me to swallow. We’re gathering all the resources we have in our hands to survive in this situation. When I started to write and publish, I did ask them if it was okay for them to be part of the narrative. My dad mumbled, “I’ll tell them that it’s fiction.” My mom said, “I think you should write whatever you want to write because nobody cares about people like us.” That permission was heavy, and I cannot abuse it.

All parents want, especially immigrant parents, is to provide better—whatever they define as better—they don’t want us to experience what they had to experience. They want to protect us and warn us about what we’ll face in society. For a long time, my parents said, “You may want to be a writer, but you’ll never make it”—not because they don’t believe in me, but because they don’t believe that society is ready or has the capacity for people like us.

ZP: Is there a poetic tradition in Taiwan?

C-LC: Mandarin Chinese is a language with a long history—one of the oldest—and it involves thousands of years of poetry writing. In Taiwan, because of the gap of martial law and the change of languages, my generation is the first to master Mandarin, written in traditional Chinese characters, so we haven’t had time to develop a poetic tradition. Recently, I have read Taiwanese poems that incorporate other spoken languages, and I admire how it reflects our diversity and history. I believe poetry is strongly bound to the land and space I’m in. Even writing in English, I have a longing for my native land.

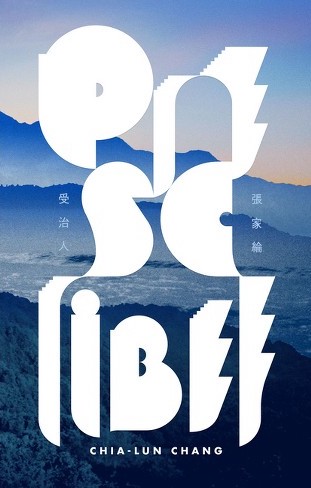

ZP: Would you describe what led you to build the book around the word “prescribee”?

C-LC: This word matches my status. The words “prescription” and “prescriber” are common but there aren’t many words for the receiver. People who receive have less vocabulary. Being ESL, I receive a lot of messages and different information. Since my vocabulary is limited, this position feels inferior in society. We observe lots of people who announce. Who are the people who receive the announcement?

“Prescribee” is not only the person who receives medical treatment but also who receives ruling by the authorized regime, and this applies to my state growing up in Taiwan. Taiwan, as an island—like many islands in modern history—has experienced long and passed over colonization. The systems of thinking and living have been changing drastically, whenever another colonizer comes. We receive the ruling and have to adopt it. According to the Treaty of Shimonoseki, Taiwan was ceded to Japan, so we were Japanese. After Japan lost the war, according to General Order No. 1, we were given back to China, during the Republican Era. We didn’t get to participate in our history. We are the protagonists in the document, but we can’t decide our fate.

As for the medical term: growing up, in a female body, I always had a voice in my head saying, “You are sick. You need treatment.” Who gave me this prescription? Then I realized, everyone around me—we’re all sick. In my grandparents’ generation, they were told they were Japanese. In my parents’ generation, they were told they were Chinese. Now, we’re not sure if we’re Taiwanese enough—or if we’re Taiwanese yet. Where are the documents that tell us who we are? Are we crazy, officially? Who can tell us if we are sick or not? What kind of medicine do we have to take to fit into the system?