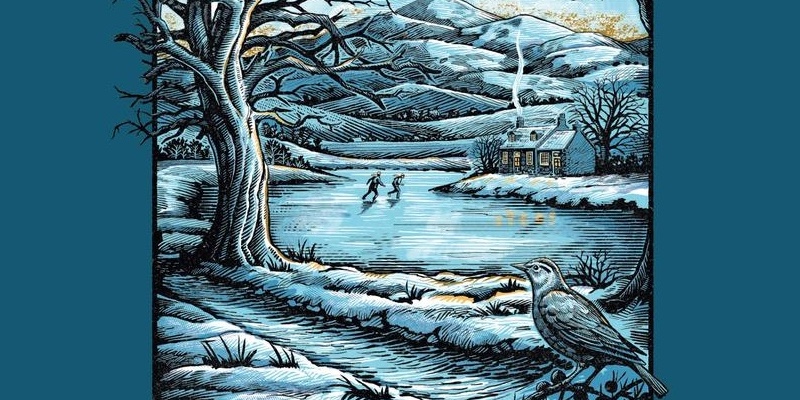

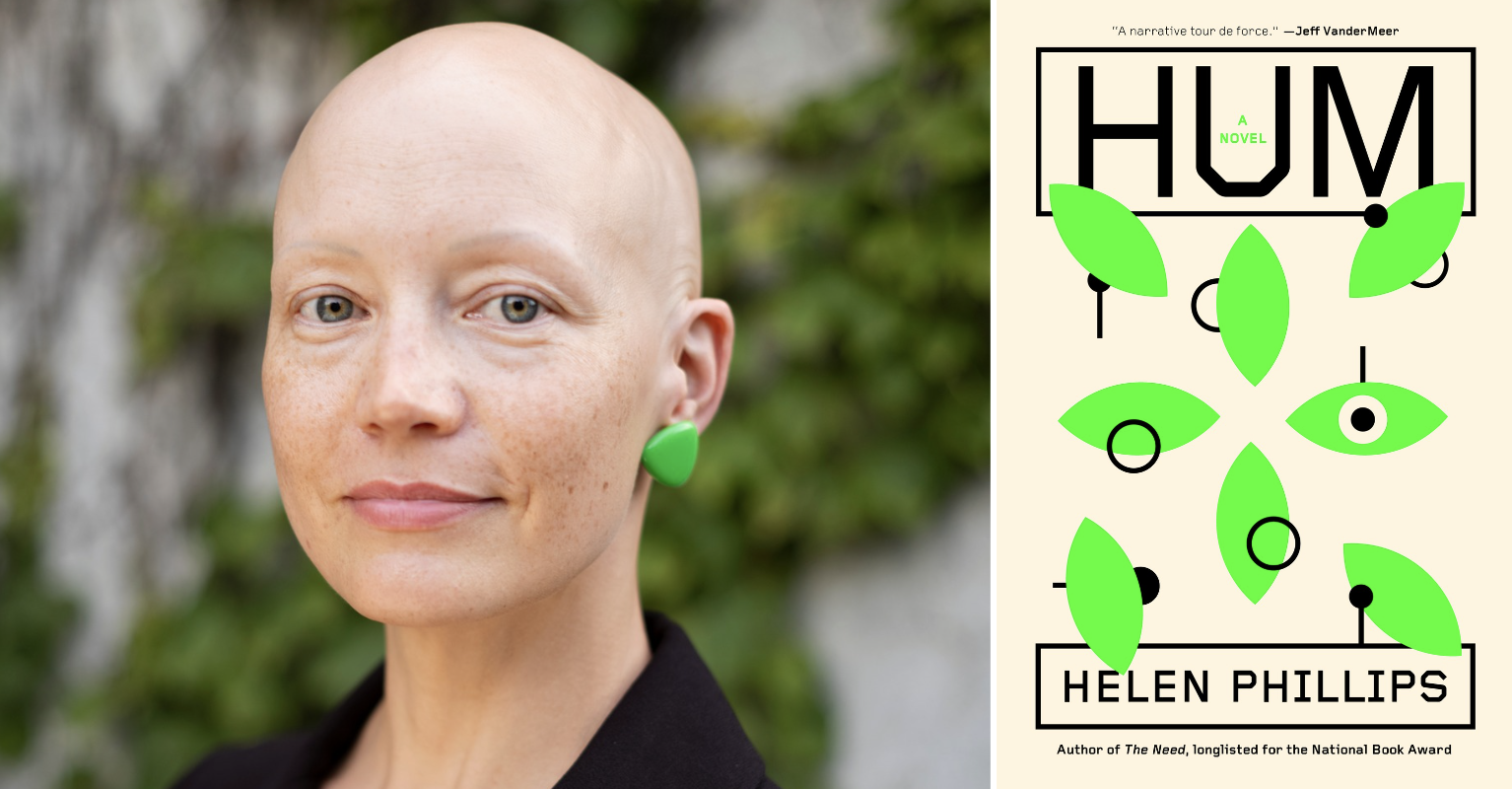

Helen Phillips’s latest novel, Hum, takes place in a near-future city in the grip of climate change and ubiquitous artificial intelligence, where the workforce has become saturated with networked androids called “hums” that excel at dentistry, rideshare driving, same-day delivery—capitalism at its shining best, or so it seems.

The novel opens with May Webb, mother of two, undergoing an experimental facial alteration procedure, for pay, because she lost her job to artificial intelligence. Flush with cash, May impulsively books a weekend retreat for her family in an urban oasis, where her children meet with sudden peril. To save her family, May places her trust in a hum with uncertain motives.

Hum is not your garden-variety technocratic dystopian novel. It’s too rooted in our present fears to feel that distant. Like the climate emergency, the generative AI explosion is happening faster than we can adapt or consider the ethical implications, such as the long shadow the technology has cast on our vocation as writers. As Phillips told me over Zoom in the midst of Brooklyn’s June heat bulb, “It seems very likely to me that a lot of AI will be used for agendas that are not the agenda of, Could we use this incredible force to create a better society?” (Full disclosure: our conversation was live-filtered through otter.ai’s transcription service, for expedience.)

*

Arturo Vidich: In your previous novels, The Beautiful Bureaucrat and The Need, you took readers on a funhouse tour of labor and motherhood, respectively. When did you know Hum was a story you wanted to tell?

Arturo Vidich: In your previous novels, The Beautiful Bureaucrat and The Need, you took readers on a funhouse tour of labor and motherhood, respectively. When did you know Hum was a story you wanted to tell?

Helen Phillips: Well, I do see this book as being a very natural third book to those other two. I think all of them have anxiety at the center of them. The anxiety that I would identify for Hum is, at base, just the experience and challenge of raising children into a future that feels incredibly uncertain, which maybe is the human condition. But I feel like it’s more so now, with AI and climate change—these two just absolute game-changing things that are staring us in the face. I write a book to come to understand my fears better. The fear in this book was parenting into this future ahead of us.

AV: I’ve had to put a filter on myself whenever I go to kids’ birthday parties so I don’t bring up Cormac McCarthy‘s The Road, or Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. Do you feel like writing this book or doing the research helps you particularly?

HP: I think that there’s something to be said for just looking at it and not avoiding it. To read books like Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace Wells, to read a lot of the other articles I read, it feels better to look at it head on—anxious, but hopefully cathartic. I think it’s an interesting project at this moment to be writing about the future. I’d been reading stuff that indicated to me that something like ChatGPT was coming, and so it’s—I guess fun isn’t quite the right word—but it’s an exciting and dynamic part of being a writer of speculative fiction to be casting my gaze forward and trying to imagine, well, when we do have super intelligent, embodied robots walking around the world with big knowledge, how will that change our lives? We’re not there yet, but I do believe that’s coming. So, yes, it’s hard to write speculative fiction that’s in the near future that can remain in the speculative realm. It catches up quickly, but at least, hopefully, imagining even five minutes into the future helps to reflect on the present moment that we’re in.

HP: I think that there’s something to be said for just looking at it and not avoiding it. To read books like Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace Wells, to read a lot of the other articles I read, it feels better to look at it head on—anxious, but hopefully cathartic. I think it’s an interesting project at this moment to be writing about the future. I’d been reading stuff that indicated to me that something like ChatGPT was coming, and so it’s—I guess fun isn’t quite the right word—but it’s an exciting and dynamic part of being a writer of speculative fiction to be casting my gaze forward and trying to imagine, well, when we do have super intelligent, embodied robots walking around the world with big knowledge, how will that change our lives? We’re not there yet, but I do believe that’s coming. So, yes, it’s hard to write speculative fiction that’s in the near future that can remain in the speculative realm. It catches up quickly, but at least, hopefully, imagining even five minutes into the future helps to reflect on the present moment that we’re in.

One thing that was really rich about the process was some of the interviews I did. I talked to Arthur Miller, who wrote The Artist in the Machine, which is about, I would say, a positive look at human–AI creative collaborations. And I interviewed Kenneth Gould, who’s a professor at Brooklyn College studying climate change and sociology. I interviewed my friend Kendall Salcido, about capitalism and international development work. One repeated theme I noticed was the idea that community is what can help us through. And it sounds so simple and maybe almost saccharine, this idea that coming together, trying to forge real human connections, is the only hope of navigating this world. But working collaboratively is really the best tool we have. So, at the end of Hum—and I want to avoid spoilers—I really did try to put the family in a circumstance where you could see them finding ways to connect.

AV: Very early on in the novel, we find out that May Webb is one of the people who trained the hums’ artificial intelligence engine to be more human. Could you talk about the endeavor of recreating and externalizing humanity when we don’t even fully understand our own compassion or cruelty?

HP: For me, some of the intrigue and fascination with artificial intelligence is very much in the realm of fantasy, because it seems that, so far, algorithms tend to accelerate bias and emphasize the worst aspects of human behavior. But if there was some way to have an artificial intelligence that was able to consolidate the wisdom, the knowledge, the ethical and philosophical understandings, and actually enact those principles, which, as humans, we find very hard to enact, what would that be like? At the same time, the hum is an instrument of advertising, so it’s constantly tied up in this other agenda.

AV: I loved that aspect—these androids constantly trying to upsell, or interrupting urgent conversations with targeted ads for products. In order to have any ad-free peace, you have to pay for that peace. What do you think about this recent viral tweet by Joanna Maciejewska: “I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes.”

HP: Yeah. I mean, I think that quote is funny and also has terrifying truth to it. At this point, it’s hard, from my understanding, to have a robot that could do your dishes or fold your laundry, rather than a robot that could write a poem for your poetry class. And that is disturbing. When I encounter a work of art, it matters to me that that work of art has a human behind it, someone else who is hauling their body through this world of ours, and having emotions and hormones and random thoughts. How do they consolidate the experience of being human and convert it into a work of art? I’m much less interested in—and maybe the otter.ai bot who’s listening to us is going to be really offended by this—but I’m much less interested in an algorithm that can create something new but only based on everything that’s already been fed into it. Maybe that will change. But for now, I care that a work of art is created by a person. I don’t know if that’s going to prove to be a very old-fashioned perspective.

AV: I feel the same. No human can take the entirety of human culture up till now and create art based on that. We’re much narrower in our experiences, which leaves a lot of room for conversation.

HP: I’m clinging to the idea that what’s so exciting about art is seeing someone else’s humanity and the idiosyncratic way they crystallize it. Nothing can be more exciting than having someone else share their inner creativity, their inner life that way. If it truly is a collaboration, I’m willing to believe that you could make interesting work that way. But I like writing.