In her memoir The Light Room, Kate Zambreno argues that the domestic drudgeries and caregiving that for centuries seemed to get in the way of sustained thinking, reading, research, and writing were, all along, their own formidable forms of art. As a book that dwells with children in a way that is almost always compassionate and never condescending, The Light Room returns readers to a kindergarten of the senses—to the basic contours of time, the colors of home and public space—and unravels the relationship between labor and the obscurely fascinating objects it produces, around which life, work, and family subsequently orbit.

Fittingly, the book begins with a tantrum over a toy. Zambreno is watching her older daughter play in Prospect Park, and the three-year-old is “set off” when another child is given a toy that the others in their “parent-child forest school” are not. Among the children, currency takes the form of magnifying glasses, buckets, wooden spoons, and maracas. Every emotion that adults feel in response to possessions and status—envy, resentment, righteous indignation—manifests in miniature, with twice the drama, in Zambreno’s toddler, who, along with the author’s partner John and their younger daughter, form the memoir’s pared-down cast of central characters. (This is the case partly because the book is set during the pandemic, when horizons for many shrank from cities down to blocks, then down to the intimate confines of living rooms that doubled as offices and schools.) The main room of the old house Zambreno rents is strewn with “blocks and toys and dolls,” “filthy rugs,” “books stacked on the console,” unfolded laundry, and unopened packages. Scattered objects overwhelm the family’s daily existence. Many of them are nonessential to survival. They are, in one way or another, toys. But what is a toy, really?

In one section of the book, which is divided into short, subtitled vignettes reminiscent of Moyra Davey’s Index Cards and Robert Walser’s Microscripts, Zambreno spends months researching farm sets and animal figurines to buy for her daughter’s fourth birthday, committed to selecting the correct horse for a toy stable and noting the difference in size, for instance, between the “Schleich Horse Club Arabian Stallion” and the “Schleich Farm World Tennessee Walker Mare.” Zambreno admits that she is “exhausted” by the search for new toys, the overconsumption, and the waste. Yet, purchasing the right toys remains as inescapable a conundrum as the pursuit of happiness.

In one section of the book, which is divided into short, subtitled vignettes reminiscent of Moyra Davey’s Index Cards and Robert Walser’s Microscripts, Zambreno spends months researching farm sets and animal figurines to buy for her daughter’s fourth birthday, committed to selecting the correct horse for a toy stable and noting the difference in size, for instance, between the “Schleich Horse Club Arabian Stallion” and the “Schleich Farm World Tennessee Walker Mare.” Zambreno admits that she is “exhausted” by the search for new toys, the overconsumption, and the waste. Yet, purchasing the right toys remains as inescapable a conundrum as the pursuit of happiness.

For a child, toys certainly hold outsized significance and are often the source of what Zambreno calls “very big feelings,” to which adults are no less prone. Similarly weighed down by the significance of objects, Zambreno describes covering a hole in her couch with a towel while teaching Zoom classes in lockdown, then taking an extra teaching gig to pay for a new couch, driven to exhaustion and frustration as she “sit[s] on this new couch all day […] trying to get reading or work done.” In Zambreno’s memoir, the objects that adults tend to be concerned with are the ones that trigger feelings of shame and anxiety. Rather than inspire play, these objects break down and wear out. Even after they are discarded, like the “broken dollar-store sleds” Zambreno finds abandoned in Prospect Park by people who “probably have a lot more money” than her and who “pay the cost of college tuition on preschools and own brownstones but balk at a decent sled,” they continue to reflect badly on their owners.

Often, however, Zambreno’s fascination with her daughters’ toys verges on aesthetic admiration. In previous books, such as Heroines and Drifts, Zambreno grounds her social critique in close reading, close looking, and close scrutiny of artists’ biographies, drawing connections between marginalized subjectivities across time and space. In The Light Room, her discussions of the aesthetic value of toys function similarly as portals, this time between the subjectivities of children and the world of adults. Take, for instance, this passage on collecting marbles:

Often, however, Zambreno’s fascination with her daughters’ toys verges on aesthetic admiration. In previous books, such as Heroines and Drifts, Zambreno grounds her social critique in close reading, close looking, and close scrutiny of artists’ biographies, drawing connections between marginalized subjectivities across time and space. In The Light Room, her discussions of the aesthetic value of toys function similarly as portals, this time between the subjectivities of children and the world of adults. Take, for instance, this passage on collecting marbles:

Sometimes I have the urge to get the children an entire bag of marbles, all their variations in color, how excited they would be. But also, when I think about it, I want an entire bag of marbles for myself. I want to roll these miniature worlds, these colorful forms, around in my palm and put them in a bowl…. I have never collected anything before, but the urge to collect childhood toys gives me a feeling that’s not quite nostalgia…. It is perhaps a longing for simple beauty.

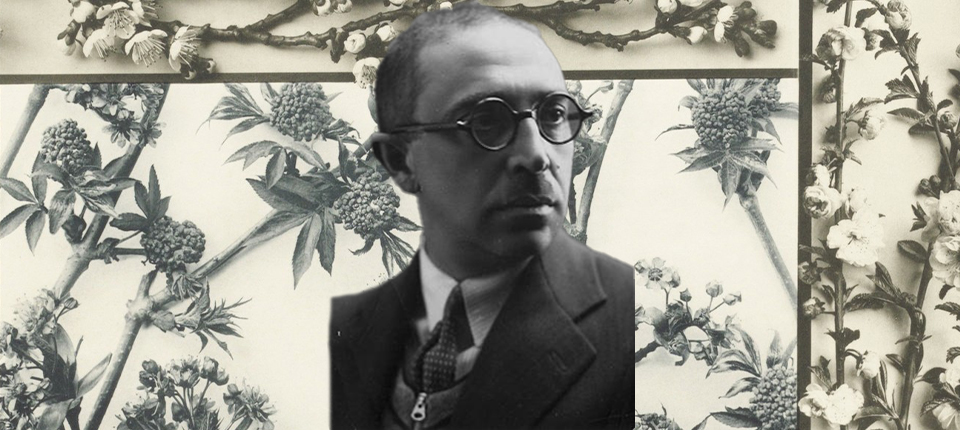

Zambreno’s eye for “simple beauty” resembles that of the artist Joseph Cornell, a recurring interlocutor in her text, who is celebrated for his eclectic shadow box assemblages made from bric-a-brac and photographs. Cornell was known to have let children play with his works, and, in 1972, the year of his death, he arranged exhibitions at the Cooper Union and Albright-Knox where he installed his boxes three feet off the floor, at the average child’s eye level. Cornell, too, had a penchant for glass marbles. In works like his early Soap Bubble Sets, after which Zambreno titles one of her vignettes, he displays them with glass cups, pipes, and prints of celestial diagrams. Another of Zambreno’s interlocutors, the artist and activist David Wojnarowicz, also collected toy horses—Breyers—as well as figurines of dinosaurs and reptiles, “talismans from an otherwise unhappy childhood.” Considering that Wojnarowicz spent much of the 1980s and early ’90s tending to and advocating for friends who’d been diagnosed with AIDS, before succumbing to the disease himself at age 37, the artist’s “attention to the small and the cosmic,” which Zambreno arguably shares, perhaps assuages what the memoirist calls the “historical awareness and planetary despair” that accompanies “mourning and caretaking of loved ones.”

If only it were as simple as saying that children play with objects and find joy in them; that, as one grows older, objects turn into burdens and sources of anxiety; and that, for a special class of people—artists—objects remain magical forever. But as we observe again and again in The Light Room, children feel anxiety and sorrow over toys, making art and contemplating artworks is stressful, serious labor, and often those tasked with being the adults in the room are given over to spontaneous urges to see marbles and miniature stables as talismanic worlds unto themselves. Not to mention the way some objects turn from being sources of vibrant wonder into “frozen capital,” sequestered like the 35-foot painting by James Rosenquist that Zambreno visits in a Newark storage facility in order to complete a writing commission (its objecthood is intimately connected to Zambreno’s work: if she cannot see it in the flesh, she cannot write about it). As she reflects on the painting, Zambreno considers Rosenquist’s “ambivalence” toward corporate commissions and feels a certain “kinship” with the artist since, as a writer, she must participate in transactions of a similar nature.

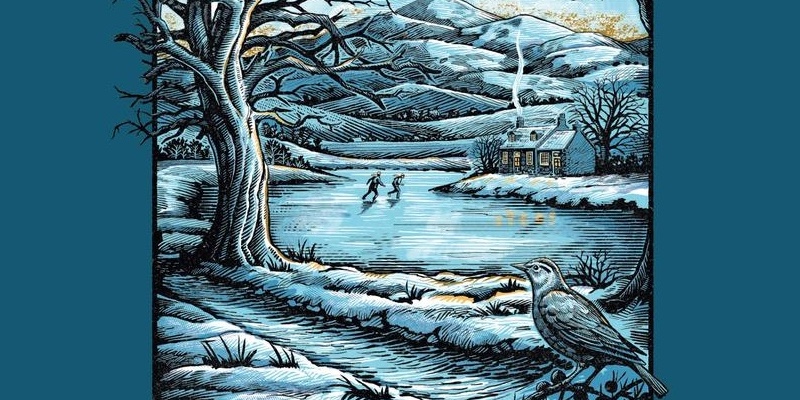

Like the art world, the culture around toys can evoke a feeling of ambivalence. As simulacra, toys themselves seem at times to refuse reality. During a snowstorm, Zambreno watches her daughter play with figurines—a panda, a penguin, a bear. This scene comes just after Zambreno expresses a desire to teach her daughter about the natural world: “I thought, if I can teach her about life in the ocean, about the variety of ecosystems, then she will care later on when she learns how greatly it is threatened because of human action.” This urge, she writes, “was a way for me to cope with an ecological sorrow that was beginning to overwhelm me.” But can toys, which inspire tantrums and spending, also inspire empathy? Can empathy—and, in particular, empathy toward the nonhuman—be taught using the meager tools we have on hand?

The great gulf between Zambreno’s ecological sorrow and the image of her daughter playing with a plastic menagerie of animals glommed together from different biomes encapsulates the central tension in this memoir. The writer wishes to impart her thoughtful way of looking at the world to an audience that is too young to grasp the severity of climate change, the pandemic, capitalism, and other systemic ills. This tension echoes a passage in Maggie Nelson’s 2021 book On Freedom. There, the critic and poet describes visiting a junkyard with her toddler son and watching him pretend to drive an abandoned coal train. The memory is a happy one, for both mother and son. But what the mother knows, and what the child doesn’t know, is that the advent of such trains marked the start of the Anthropocene, which will make the earth uninhabitable for his and future generations.

The great gulf between Zambreno’s ecological sorrow and the image of her daughter playing with a plastic menagerie of animals glommed together from different biomes encapsulates the central tension in this memoir. The writer wishes to impart her thoughtful way of looking at the world to an audience that is too young to grasp the severity of climate change, the pandemic, capitalism, and other systemic ills. This tension echoes a passage in Maggie Nelson’s 2021 book On Freedom. There, the critic and poet describes visiting a junkyard with her toddler son and watching him pretend to drive an abandoned coal train. The memory is a happy one, for both mother and son. But what the mother knows, and what the child doesn’t know, is that the advent of such trains marked the start of the Anthropocene, which will make the earth uninhabitable for his and future generations.

“Here I am,” Nelson writes, “still feeling the unprecedented (in my life, anyway) sensation of simple, total happiness, of beholding a new beginning in this world…. Is there any new beginning that doesn’t already contain the seeds of its end?” Likewise, in much of The Light Room, Zambreno’s compassion for her young daughters arcs across a terrible and frightening chasm of knowledge: Zambreno must somehow, while preserving the simple beauty and joy of everyday life, prepare her children for survival on the earth they are to inherit, one on which, to quote from Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects, “The end of the world has already occurred.” In light of this burden, a plastic horse means nothing and everything.

“Here I am,” Nelson writes, “still feeling the unprecedented (in my life, anyway) sensation of simple, total happiness, of beholding a new beginning in this world…. Is there any new beginning that doesn’t already contain the seeds of its end?” Likewise, in much of The Light Room, Zambreno’s compassion for her young daughters arcs across a terrible and frightening chasm of knowledge: Zambreno must somehow, while preserving the simple beauty and joy of everyday life, prepare her children for survival on the earth they are to inherit, one on which, to quote from Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects, “The end of the world has already occurred.” In light of this burden, a plastic horse means nothing and everything.