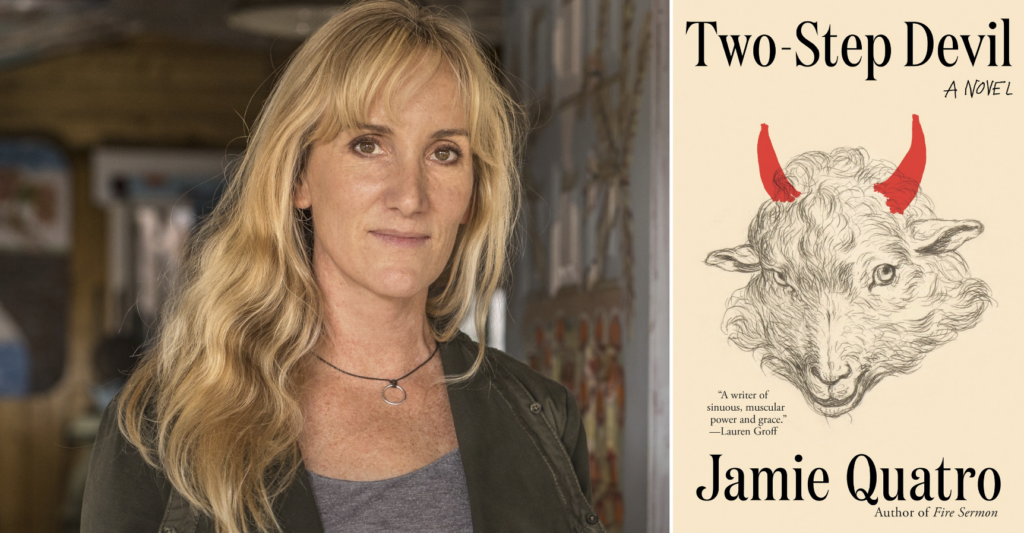

Every time I read Jamie Quatro’s fiction—from her debut collection I Want to Show You More, to her 2018 novel Fire Sermon, to her short stories in the New Yorker—I experience the same edge-of-my-seat pleasure. Quatro’s characters are as alive as flesh-and-blood people; the Southern landscape they inhabit feels solid enough to stand in. But always, thrillingly, the otherworldly eventually slips in, dissolving the boundary between the real and the fantastic.

Every time I read Jamie Quatro’s fiction—from her debut collection I Want to Show You More, to her 2018 novel Fire Sermon, to her short stories in the New Yorker—I experience the same edge-of-my-seat pleasure. Quatro’s characters are as alive as flesh-and-blood people; the Southern landscape they inhabit feels solid enough to stand in. But always, thrillingly, the otherworldly eventually slips in, dissolving the boundary between the real and the fantastic.

Quatro’s latest book Two-Step Devil, plays with this boundary in fresh and riveting ways. Formally innovative and boldly imaginative, the novel brings together two vastly different protagonists: a 70-year-old “Prophet” who lives atop an Alabama mountain painting his visions, and Michael, the 14-year-old girl he rescues from the hands of traffickers. As the Prophet cares for Michael, their relationship deepening, his certainty grows that she’s a messenger sent by God to deliver his end-time messages to the President. All he must do is convince her of her role while enduring visitations by Two-Step, the jigging devil who appears to sow doubt in his mind.

I chatted with Quatro over email about her fundamentalist Christian upbringing, cosmic coincidences, and the perils of having fun in the writing process.

*

Nicole Graev Lipson: Your previous two books delved into themes of desire, marital infidelity, and religious transgression. I’m curious where you see Two-Step Devil fitting into your body of work. Do you consider it an artistic departure?

Jamie Quatro: At first, I typed: Yes, exclamation point. But then I gave it more thought and realized I need to qualify. I Want to Show You More contains six interconnected stories about a woman involved in an emotional affair, but most of the other stories are experimental and probe the boundary between the real and the imagined, material and immaterial. If Fire Sermon took those emotional affair stories and widened the lens, moving from hypothetical infidelity to actual consummation and then pushing the narrative deep into the physical and spiritual consequences, Two-Step Devil might be a return to, and expansion of, the visionary/experimental mode.

But as far as point of view goes, yeah, this novel marks a dramatic departure. Fire Sermon is narrated by a woman who is like me in many ways. Two-Step Devil has three narrators: a 70-year-old visionary artist known as the Prophet, an adolescent victim of sex trafficking named Michael, and an enigmatic “devil” figure called Two-Step. With my first two books, people often asked, “How autobiographical is your work?” I don’t anticipate getting that question this time!

Overall, though, this book is still signature JQ. God, longing, sex, death, temptation, the mystical, the South. I swear my next book will be about, I don’t know…silk trading in ancient Greece.

NGL: Your writing moves so agilely between the real and the otherworldly. Within a few sentences you can take us from a relatable moment of human caregiving to a dancing devil in a cowboy hat offering his commentary. Is this porousness hard to achieve—or is it part of how you experience the world?

JQ: I would like to say that I experience a firm line between the material and immaterial. Or that I believe in only the material. This seems the rational, sane response. But I’m more of a mystic than I often like to admit. I just finished reading Oxford theologian and Anglican bishop N.T. Wright’s Surprised by Hope. He talks about how the common conception of heaven—some place “out there” where our souls go when we die—is a misconception. The idea that the material world/bodies are bad, and the immaterial world/souls are good, is a hangover from Plato. Wright argues that heaven, ultimately, is here. This planet, these bodies. Not to downplay darkness and evil, but ultimately good theology, good eschatology, says that this is not a throwaway planet inhabited by throwaway bodies. Our future immortality is not some floating-cloud state of bliss; nor is it annihilation. The radical Christian idea is that heaven has already begun to break into earth, almost as if through a scrim or a veil, in the form of the resurrected body of Jesus. The consummation will be the full reunion of heaven and earth. Martin Luther said that the right response to “what would you do if the world was ending tomorrow” is “plant an apple tree.” How differently would we treat the planet if we believed it was meant for healing, not destruction?

JQ: I would like to say that I experience a firm line between the material and immaterial. Or that I believe in only the material. This seems the rational, sane response. But I’m more of a mystic than I often like to admit. I just finished reading Oxford theologian and Anglican bishop N.T. Wright’s Surprised by Hope. He talks about how the common conception of heaven—some place “out there” where our souls go when we die—is a misconception. The idea that the material world/bodies are bad, and the immaterial world/souls are good, is a hangover from Plato. Wright argues that heaven, ultimately, is here. This planet, these bodies. Not to downplay darkness and evil, but ultimately good theology, good eschatology, says that this is not a throwaway planet inhabited by throwaway bodies. Our future immortality is not some floating-cloud state of bliss; nor is it annihilation. The radical Christian idea is that heaven has already begun to break into earth, almost as if through a scrim or a veil, in the form of the resurrected body of Jesus. The consummation will be the full reunion of heaven and earth. Martin Luther said that the right response to “what would you do if the world was ending tomorrow” is “plant an apple tree.” How differently would we treat the planet if we believed it was meant for healing, not destruction?

And if you’re a writer, you don’t have to believe one bit of the above to know that there’s something mystical going on when you’re deep in the writing of a book. “Coincidences” manifest everywhere. I just read Sheila Heti’s Harper’s essay on A Course In Miracles. She writes about how she’d noticed “enough uncanniness in the writing of books to suspect that the spiritual realm participates somehow, though I couldn’t say how.” I’ve read just enough quantum physics to understand that the miraculous and the scientific are not mutually exclusive. In some way, we’re creating these miracles ourselves. There’s a collaboration going on with God, the Universe, the Muse… some passage back and forth between the veil.

NGL: I was so moved by the scenes between the Prophet and his estranged son Zeke, who has come to see the father he once revered as a “crazy old man.” At one point Zeke tells his father, “Kids believe whatever parents tell them till they grow up and realize they were tricked.” Not every parent has end-time visions—but I suppose every parent must eventually reckon, in their own way, with falling from grace in their child’s eyes. Was this something you were interested in exploring?

JQ: I’ve had to reckon with the form of Christianity I inherited from my parents (and they inherited from their parents, and so on). I was raised in the Church of Christ—no drinking, no dancing, no instruments in worship, adult baptism required for salvation. I’ve left that kind of fundamentalism behind. I’m lucky that I was able to keep relationships while ditching the baggage. Not everyone has that luxury. I know people who were victims of severe religious abuse and who absolutely needed to cut all ties, much in the way Zeke needed to cut ties with his father. Our church was strict, but my parents weren’t, and I think that particular grace is part of what allowed me to remain a practicing Christian.

I’m an Episcopalian now, but I can look back and see many things I’m grateful for in the ways I was raised. I was made to read and memorize the Bible, which has served me well as a reader, fiction writer, and scholar. I learned to sing in four-part harmony. I learned that church can look like a community of people committed to helping one another through adversity and suffering.

NGL: This book explores weighty themes, but there’s also a wonderful playful quality to it. You even approach structure playfully—the narrative dances backward and forward across time, moves between narrators, and even adopts a script format for a while. I got the sense you had some fun while writing it! Am I correct?

JQ: Yes and no. It took a long time to find the right form for Two-Step’s section, “Gospel.” It came out as a long essay, the devil’s diatribe. But it was too disconnected from the rest of the novel. What did Two-Step’s rant have to do with the Prophet and Michael? I knew that I wanted his voice to take this hidden story of two marginalized characters and cast it in the biggest cosmic light, to give it the weight of eternity… but how?

I tried it as a Q&A session next. The Prophet and the Devil in conversation. That version was too disembodied. I tried it as a screenplay—that didn’t work either, but I could tell I was getting close. I went to Yaddo, facing down my deadline, and happened upon an anthology of one-act plays. I read all of them and realized I’d found my form. The image of the stage was already embedded in the book. When Two-Step first appears, he removes his hat and takes a bow “as if he’s up on a stage, hearing applause.” The Prophet envisions himself on a stage, doing hand-to-hand combat with the devil. Michael floats up out of her body in moments of trauma and watches herself as she’d watch a performance. I’d say finding that book on that shelf was another one of those cosmic coincidences, but the truth is probably more like: my subconscious knew all along that the devil was a performer, and would require a stage. It just took my conscious mind some time to recognize the gift I’d left for myself within the text.

Once I’d found the play format, yes, I had fun writing it. Too much fun. Joy Williams told me that if you find yourself having fun while you’re writing you should be suspicious of what’s coming out. I think she’s spot on. Having that much fun made me want to keep writing. Which made the play way, way too long. Thank God for editors.