Florida Is a Strange Wilderness Growing Inside Me

Click to enlarge and scroll.

An excerpt from State of Paradise by Laura van den Berg

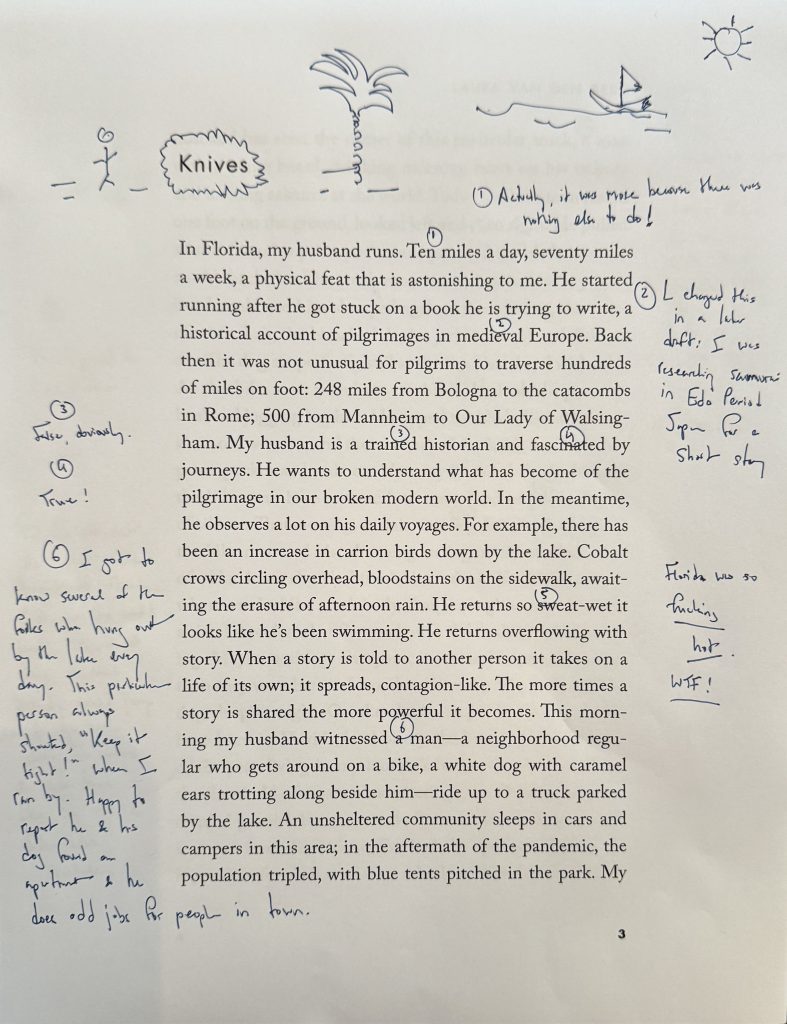

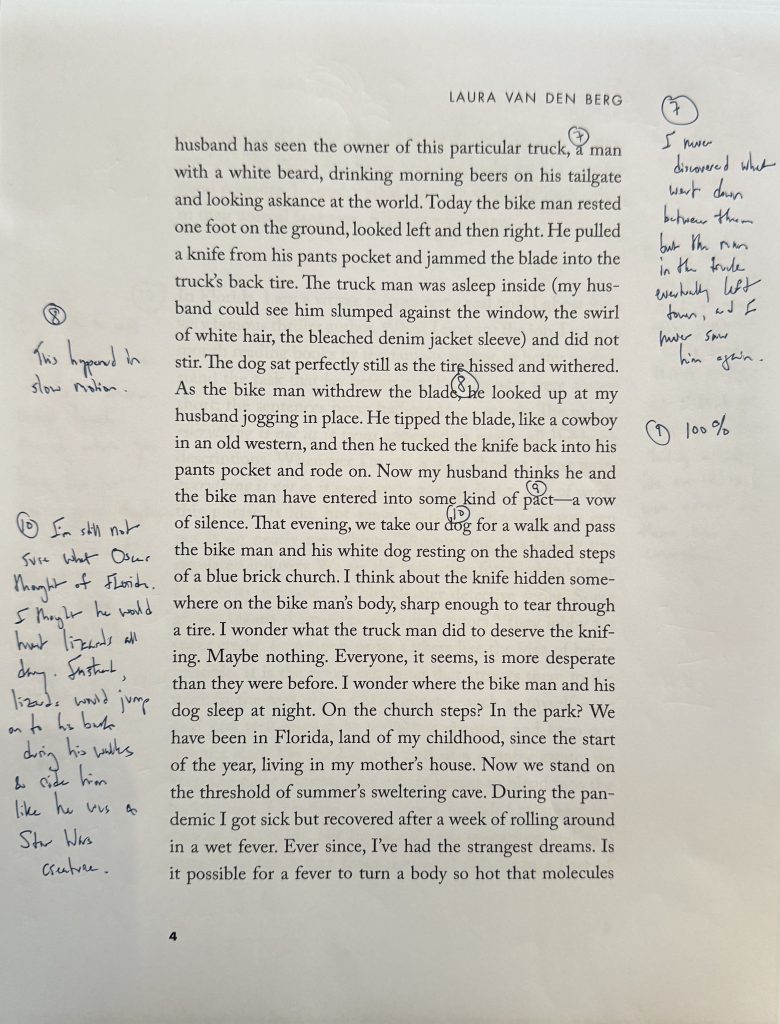

In Florida, my husband runs. Ten miles a day, seventy miles a week, a physical feat that is astonishing to me. [1] He started running after he got stuck on a book he is trying to write, a historical account of pilgrimages in medieval Europe. [2] Back then it was not unusual for pilgrims to traverse hundreds of miles on foot: 248 miles from Bologna to the catacombs in Rome; 500 from Mannheim to Our Lady of Walsingham. My husband is a trained historian [3] and fascinated by journeys. [4] He wants to understand what has become of the pilgrimage in our broken modern world. In the meantime, he observes a lot on his daily voyages. For example, there has been an increase in carrion birds down by the lake. Cobalt crows circling overhead, bloodstains on the sidewalk, awaiting the erasure of afternoon rain. He returns so sweat-wet it looks like he’s been swimming. [5] He returns overflowing with story. When a story is told to another person it takes on a life of its own; it spreads, contagion-like. The more times a story is shared the more powerful it becomes. This morning my husband witnessed a man—a neighborhood regular who gets around on a bike, a white dog with caramel ears trotting along beside him—ride up to a truck parked by the lake. [6] An unsheltered community sleeps in cars and campers in this area; in the aftermath of the pandemic, the population tripled, with blue tents pitched in the park. My husband has seen the owner of this particular truck, a man with a white beard, drinking morning beers on his tailgate and looking askance at the world. [7] Today the bike man rested one foot on the ground, looked left and then right. He pulled a knife from his pants pocket and jammed the blade into the truck’s back tire. The truck man was asleep inside (my husband could see him slumped against the window, the swirl of white hair, the bleached denim jacket sleeve) and did not stir. The dog sat perfectly still as the tire hissed and withered. As the bike man withdrew the blade, he looked up at my husband jogging in place. [8] He tipped the blade, like a cowboy in an old western, and then he tucked the knife back into his pants pocket and rode on. Now my husband thinks he and the bike man have entered into some kind of pact—a vow of silence. [9] That evening, we take our dog for a walk [10] and pass the bike man and his white dog resting on the shaded steps of a blue brick church. I think about the knife hidden somewhere on the bike man’s body, sharp enough to tear through a tire. I wonder what the truck man did to deserve the knifing. Maybe nothing. Everyone, it seems, is more desperate than they were before. I wonder where the bike man and his dog sleep at night. On the church steps? In the park? We have been in Florida, land of my childhood, since the start of the year, living in my mother’s house. Now we stand on the threshold of summer’s sweltering cave. During the pandemic I got sick but recovered after a week of rolling around in a wet fever. Ever since, I’ve had the strangest dreams. Is it possible for a fever to turn a body so hot that molecules are rearranged? Is our life just on pause or is this pause now our life? [11] The white dog barks. Our dog barks back. Twice for good measure. I wonder what they are saying to each other, in their animal language. All the people wave.

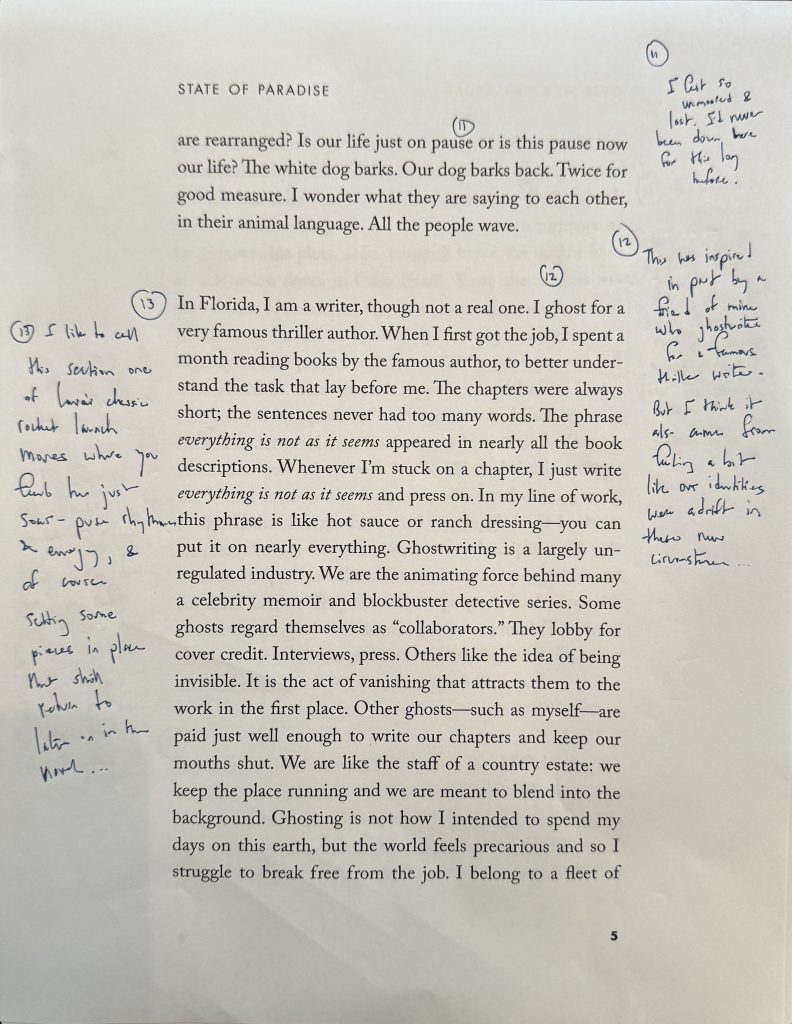

We are like the staff of a country estate: we keep the place running and we are meant to blend into the background.

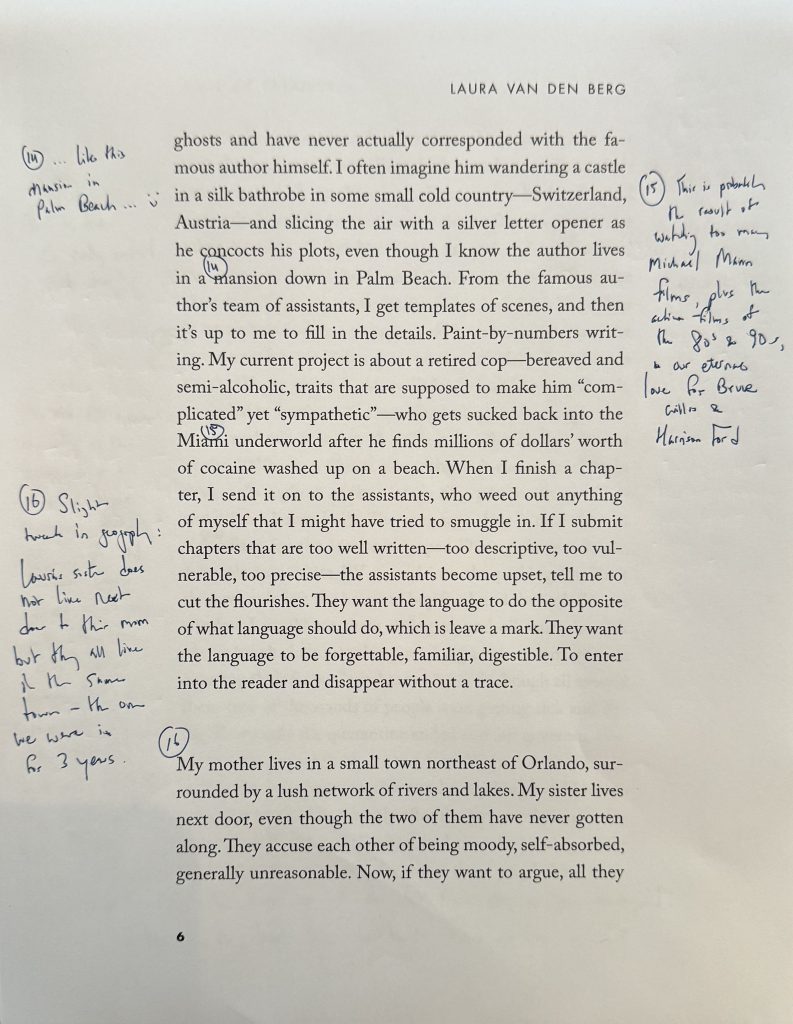

In Florida, I am a writer, though not a real one. [12,13] I ghost for a very famous thriller author. When I first got the job, I spent a month reading books by the famous author, to better understand the task that lay before me. The chapters were always short; the sentences never had too many words. The phrase everything is not as it seems appeared in nearly all the book descriptions. Whenever I’m stuck on a chapter, I just write everything is not as it seems and press on. In my line of work, this phrase is like hot sauce or ranch dressing—you can put it on nearly everything. Ghostwriting is a largely unregulated industry. We are the animating force behind many a celebrity memoir and blockbuster detective series. Some ghosts regard themselves as “collaborators.” They lobby for cover credit. Interviews, press. Others like the idea of being invisible. It is the act of vanishing that attracts them to the work in the first place. Other ghosts—such as myself—are paid just well enough to write our chapters and keep our mouths shut. We are like the staff of a country estate: we keep the place running and we are meant to blend into the background. Ghosting is not how I intended to spend my days on this earth, but the world feels precarious and so I struggle to break free from the job. I belong to a fleet of ghosts and have never actually corresponded with the famous author himself. I often imagine him wandering a castle in a silk bathrobe in some small cold country—Switzerland, Austria—and slicing the air with a silver letter opener as he concocts his plots, even though I know the author lives in a mansion down in Palm Beach. [14] From the famous author’s team of assistants, I get templates of scenes, and then it’s up to me to fill in the details. Paint-by-numbers writing. My current project is about a retired cop—bereaved and semi-alcoholic, traits that are supposed to make him “complicated” yet “sympathetic”—who gets sucked back into the Miami underworld after he finds millions of dollars’ worth of cocaine washed up on a beach. [15] When I finish a chapter, I send it on to the assistants, who weed out anything of myself that I might have tried to smuggle in. If I submit chapters that are too well written—too descriptive, too vulnerable, too precise—the assistants become upset, tell me to cut the flourishes. They want the language to do the opposite of what language should do, which is leave a mark. They want the language to be forgettable, familiar, digestible. To enter into the reader and disappear without a trace.

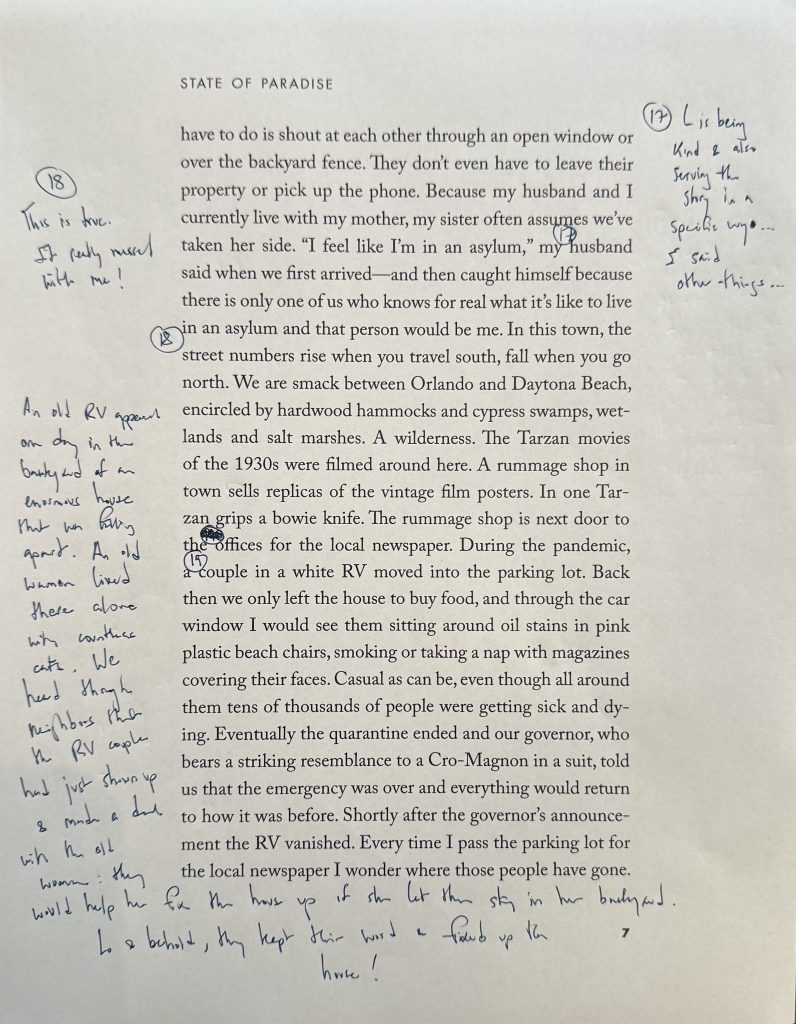

My mother lives in a small town northeast of Orlando, surrounded by a lush network of rivers and lakes. My sister lives next door [16], even though the two of them have never gotten along. They accuse each other of being moody, self-absorbed, generally unreasonable. Now, if they want to argue, all they have to do is shout at each other through an open window or over the backyard fence. They don’t even have to leave their property or pick up the phone. Because my husband and I currently live with my mother, my sister often assumes we’ve taken her side. “I feel like I’m in an asylum,” [17] my husband said when we first arrived—and then caught himself because there is only one of us who knows for real what it’s like to live in an asylum and that person would be me. In this town, the street numbers rise when you travel south, fall when you go north. [18] We are smack between Orlando and Daytona Beach, encircled by hardwood hammocks and cypress swamps, wetlands and salt marshes. A wilderness. The Tarzan movies of the 1930s were filmed around here. A rummage shop in town sells replicas of the vintage film posters. In one Tarzan grips a bowie knife. The rummage shop is next door to the offices for the local newspaper. During the pandemic, a couple in a white RV moved into the parking lot. [19] Back then we only left the house to buy food, and through the car window I would see them sitting around oil stains in pink plastic beach chairs, smoking or taking a nap with magazines covering their faces. Casual as can be, even though all around them tens of thousands of people were getting sick and dying. Eventually the quarantine ended and our governor, who bears a striking resemblance to a Cro-Magnon in a suit, told us that the emergency was over and everything would return to how it was before. Shortly after the governor’s announcement the RV vanished. Every time I pass the parking lot for the local newspaper I wonder where those people have gone.

The newspaper has an advice column, Ask Ava. In ancient times, pilgrims journeyed to the Temple of Apollo, to consult the Oracle of Delphi on vital matters, even though the Oracle was known for inscrutable replies. I wonder if Ava regards herself as a modern-day Oracle. Today’s letter writer is seeking counsel about a friend, a woman she’s known for years. During the quarantine, the friend started texting her photos late at night. In each one, she looked more and more like the letter writer. She cropped her hair and dyed it black. She ordered new clothes and makeup. She tweezed her eyebrows into skinny arches. After the governor announced that the pandemic had been defeated, the two women went out to lunch and the letter writer said it was like sitting across from a slightly different version of herself. The friend even wore the exact same T-shirt, mint green with a pink pineapple on the front. Like she’s been in my head. The letter writer is worried that her description of this situation makes her sound unhinged. Perhaps she is the one who has suffered a psychological collapse. All those hours spent alone during the quarantine, watching the news and doomscrolling and getting lost in MIND’S EYE, a virtual reality meditation device made by ELECTRA, a Miami-based tech company. Nevertheless, she has her friend’s transformation saved, photo by photo, on her phone. One night she was watching TV and glimpsed a face—more specifically the face of her friend, which now looked a lot like her own self—filling her living room window like a small, round moon. After that, she started carrying a pocketknife. I am frankly surprised Ava has taken this one on. It seems like a lot for an advice columnist to handle. Ava says that some people are like cosmic vacuums, always searching for other selves to consume. She advises the letter writer to sever the friendship and believes the friend will simply move on to another host. I want to ask Ava if she’s ever seen Single White Female or Fatal Attraction. What if the breakup doesn’t take? Good luck with this one! Ava says.

Once, I took a self-defense class for women. The class was held in a one-room studio in a strip mall. Dingy white walls. A toilet that wouldn’t stop running. Our main task was to fend off a man with a rubber knife. The man would rush up behind us and press the blade to our throats and say something menacing like bitch, you’re coming with me. Next the instructor would walk us through how to escape. First, shrug your shoulders to your ears. Second, grab the attacker’s wrists. Third, yank the attacker’s arms down while also hurling your own weight toward the floor. But don’t sit! You want to stay standing so you can run away. In the event of an actual attack, the odds of us remembering this sequence seemed very low. Still, we all gamely struggled from one step to the next until the fake attacker—who, in my judgment, seemed to take a little too much pleasure in saying bitch, you’re coming with me—gave in and released us. The last woman to attempt escape did not follow these instructions. Instead she made fists and bent her arms like she was sitting down in a chair. Next she rammed the points of her elbows into the fake attacker’s ribs. He dropped the knife and staggered backward, as if he were the one who’d been stabbed. When it was time for her to run, she didn’t just do a sad lap around the classroom, like the rest of us. She bolted out the door and into the parking lot and she did not come back. We gathered around the windows and watched her figure grow smaller and smaller, her long brown ponytail trailing behind her like the tail of a kite. That woman had freakishly pointy elbows, the instructor told us. Like knives, those elbows. That move would not work for a regular person, with nonlethal elbows, just so you know. I learned a lot from the class, though none of it came from the instructor. For example, I learned that once you start running it can be hard to stop.

In Florida, a summer storm can feel like the end of the world is being summoned. These storms roll in most afternoons, which is to say there is a regular feeling of apocalypse. The clouds turn a dense ash black, as though nightfall has arrived hours ahead of schedule. Lightning that looks like it means to split the sky. Thunder that will make a glass tremble on a table. Blue blasts of rain. The windows leak rainwater; dirt levitates in the backyard. Hail sails down through the green boughs of trees, leaves spiderwebs on car windshields, smashes roof shingles. We watch our reflections melt and twist in the rain-soaked windows. This weather passes so quickly I’ll look outside and can’t be sure if I dreamed the ferocious storm or its flat blue aftermath, which is exactly how I felt during the pandemic, after I emerged from that fevered week, unsure if the flat blue aftermath was real life or if real life was lost forever and the world I was stepping into now was nothing more than a long, strange dream.

The passenger door swings open and a woman in a denim skirt and a black tank top hurls herself—or is hurled—onto the street.

During one of these afternoon storms our phones hum with tornado warnings. “Where do we go?” my husband asks my mother, who is reading Francis Bacon’s incomplete utopian novel, New Atlantis, in the living room. “Anywhere but outside,” she replies. My mother has taken an interest in utopian texts, now that Florida seems to be heading in the opposite direction, though every time she describes one of these alleged paradises they sound a little terrifying. Too much manual labor and religious fervor. In the end, my mother often seems disappointed by these utopias too; she is still searching for her true north. My husband, meanwhile, is disturbed that my mother’s house does not have a single windowless room. Unlike my childhood home, which had a basement. The concrete bottom shimmered with water and rats scratched out nests in the stucco walls. My father was always scattering green pellets of rat poison on the wood staircase. The house was very old and I had to venture down there periodically to flip the circuit breakers. I never used a flashlight, because I was too scared to see what was writhing around in the water below. I took one step at a time with my arms extended, fingers curling around the shadows, the poison pellets crunching under my shoes. I can remember feeling as though all the volatility in our house was alive in the water and the walls, luring me closer. So basements in Florida are a frightful thing even if they do give you a place to shelter during a tornado. I text my sister, to ask what she thinks we should do, but she doesn’t reply until the storm is at full blast. Sorry, she says. I was meditating. During the pandemic, my sister became addicted to MIND’S EYE, to putting on her white headset and sliding down into other worlds. During the quarantine, ELECTRA representatives got special permission to drive all over the state and leave free headsets on doorsteps. An alleged act of public service, to help people cope with the isolation, but still there was something strange about a black van parking in the middle of the street and unleashing a small flood of masked ELECTRA employees, each holding a white pyramid of shrink-wrapped headsets. Don’t take a shower, my sister advises. Or wash any dishes. This particular storm is a tropical system and has some staying power. My mother continues to read Francis Bacon undisturbed as the lights flicker and paintings shudder on the walls. All night my husband and I listen to the lashing rain, to the lightning that summons a cracking brightness. Our dog stands on the foot of the bed and growls. Like there are forces he wants to keep out. In the morning, I walk the dog on wet sidewalks papered with green leaves. Together we leap over fallen branches that look like the severed arms of giants. At an intersection, a white car blows through a stop sign. The windows are fogged; I hear screaming inside. The passenger door swings open and a woman in a denim skirt and a black tank top hurls herself—or is hurled—onto the street. I start in her direction, pulling the panting dog along behind me. “Hey,” I call out to her. “Are you okay?” The woman turns from the car and races down an alley, a skinny dirt path that cuts between the rows of houses. I don’t get a look at the driver before they flee, the open passenger door swinging wildly. By the time we reach the alley the woman is gone. “Be careful going out after storms,” my mother advises when we get home. “People get electrocuted by downed wires all the time.” The news is reporting that the tornado inhaled roofs and flattened fences in neighboring towns. I watch shaky camera footage of a man surveying his vanquished lawn. All the windows have been blown out; the roof is gone. In what used to be a living room the furniture is now a smashed heap of debris. I seek out what is still recognizable: a lampshade, a cracked TV screen. The man’s father in a wheelchair, shaking his fist at the heavens above. The soaking red of police lights, which make me think only of the visitation of terror, as opposed to the promise of relief, despite what the books I ghostwrite would have you believe. The absence of panes and shingles, that armor against the elements, reveals the house for what it really is—a frame, an outline, a tender suggestion of shape. I get a garbage bag and a rake and collect the branches from my mother’s yard. Strange things surface in the dirt after a big storm. A green plastic kazoo. A blue lighter. A metal dog tag, faded and bone-shaped, the lettering inscrutable. A pearl button. Where have these objects been hiding? I imagine a cave system underneath my mother’s yard, kidney-shaped caverns filled with colorful plastic toys. Today with the rake I uncover a white porcelain knob, cut clean in half, as though severed by a very sharp knife.

A place outside time. This is the phrase I overhear my husband using as he tries to describe Florida to his father over the phone. His father lives in a high-rise condo in New Jersey, and he is concerned that we are still down here. On the news, there is constant talk about Florida’s post-pandemic spiral. Speculation about whether the state is experiencing an ecological and spiritual succession. There is talk about militias creeping out of the swamp. There is talk of vandals. There is talk of literal highway robbery. (Our Cro-Magnon governor denies any of this is happening, even though there are reports that some of these forces are amassing in his name.) For the time being, I can ghostwrite my books and shop specials at the grocery and take my niece to the water park, but no one knows how much longer this version of our world will last. “Sometimes I can’t believe a place like this exists,” my husband says as we speed down a gleaming white limestone road that cuts through a palm forest, or ride an airboat around a swollen lake. Florida has a past, as all places do, but these days everyone is uncertain about its future.

Here are some facts, from when I lived here last.

Days that felt like they’d been drenched in tar. Two attempts, one experimental and one sincere. One hospitalization, in Fort Lauderdale. During my time at the Institute, I saw and experienced things I have never discussed with another human soul. A pact of silence I have made with myself. This all happened nearly two decades ago and I have lived many other lives since then, and yet the feeling of being lost in a vast wilderness—wandering and wandering until you get so tired all you want is to lie down and sleep—is never far.

In the year before I moved away from Florida, I spent hours in the all-night Denny’s with my best friend at the time, a girl I’d met in an outpatient therapy group, eating pancakes and discussing our plans for self-annihilation like two criminals plotting the heist of a lifetime. Secretly I had decided that I wanted to live, and somehow talking about death with another person made the prospect of it feel further away. Turned it into a story we could not stop telling. Then I was, to my great surprise, admitted to a doctoral program in literature, all the way up in Boston. I was twenty-two and I had only ever lived in Florida. I had not told this girl, or anyone else, that I’d even applied. Stealing away like a thief in the night seemed like the only way to go, although now, all these years later, Florida has figured out a way to call me back. My best friend felt betrayed by my sudden departure and so we stopped speaking. Because I had resolved to leave the wilderness I’d assumed that she would find her way out too. Desperation can make people mercenary like that—you spot an exit and you start running toward it and you don’t look back. You just do your best to convince yourself that the other person is right behind you. Several years ago, I learned, from a mutual friend, that this other girl did not make it out. Only by the time the wilderness took her she was not a girl but a woman, married with children. I did not ask how she did it. If she used a weapon. A knife. Which used to be integral to her master plan back when we were still young. It was around this time that I started to wonder if the wilderness is not something a person can choose to leave. Rather it is a place that lives inside us. A landscape with its own intelligence and design.

I left Florida to become a student of literature, which I did not enjoy as much as I had anticipated. For one thing, I struggled to understand my classmates, who all knew how to style winter scarves. Each time I tried to wear a winter scarf I felt like I was being strangled. I met my husband in a university lecture hall. At the time, he was on his way to becoming a doctor of history, and by chance we both attended a talk on Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, a novel about a mathematician living in a futuristic city made entirely of glass apartment buildings. The character’s best friend is a state-sponsored poet who recites his work at public executions, and his lover is a spy for the Bureau of Guardians. The mathematician is the chief engineer for a spaceship, built for the purpose of colonizing other planets. He starts a journal with the hope it can be smuggled onto the completed spaceship. That some small part of him can escape. We was written in the early 1920s, and yet as I listened to the lecturer discuss the themes I did not feel like I was in the presence of something very old or something that existed in an inconceivable future, but rather a reality that I might meet in my lifetime. It was snowing outside; the lecture hall windows looked like they were covered by white curtains.The man I would end up marrying was sitting next to me and he was not wearing a scarf. His copy of We was open and I noticed one passage had been heavily underlined, with little stars drawn in the margins. “What’s that?” I whispered, poking him in the arm, and he slid the book over in my direction. The knife is the most durable, immortal, the most genius thing that man created. The knife was the guillotine; the knife is the universal means of solving all knots; and along the blade of a knife lies the path of paradox—the single most worthy path of the fearless mind. I had forgotten to bring my copy of We to the lecture, so the book stayed between us. Afterward, we walked to a coffee shop, sliding around in the snowy streets. Before long, we had merged our paltry furniture into a rented apartment and undertaken a life of domestic contentment that I had not ever imagined would be available to me. In the end, I never finished my dissertation, despite spending years slogging through coursework. I arrived at the realization that I did not want to spend my life writing about books that had already been written; rather, I wanted to write stories that did not yet exist. My adviser thought this was a mistake. “Writers would be nothing without us,” he sniffed. My husband did succeed in becoming a doctor of history, and after he finished his degree we moved from one city to another for his teaching jobs. I liked this itinerant life; so long as I stayed in motion I thought the wilderness would never catch me. When I landed the ghostwriting job, I told myself that becoming a ghost at least got me closer to my goal than a dissertation on Chaucer. Technically speaking I was participating in the creation of books that did not yet exist, even if they were not stories that I myself had imagined or would ever have chosen to tell.