Ten years ago, I stopped writing lyric poetry. I had a couple of slim, well-received collections to my name, and my poetry occasionally appeared in a magazine with pedigree, like Poetry. One time, an editor at The New Yorker even mailed a personalized, encouraging rejection on letterhead. (They rebuffed poems by paper in the good old days.) Still, the cupboard was no longer stocked with stanzas. Perhaps I needed a break, a sabbatical.

A good lyric poem, after all, takes toil. Sometimes a poem will fall out of the sky fully formed like a meteorite, but such cosmic events, though real, are rare. A good lyric poem also takes a toll. Immediately upon finishing your first-person meditation on grandpa’s box of old photos or that first fallen leaf of the season, you face a void. You have to start over.

And the longueurs between lyric poems can be long. Elizabeth Bishop published a very slim body of poems in her lifetime. (Famously, she fussed with “The Moose” for 20 years.) The Canadian poet Bruce Taylor seems to average one book of poems a decade. Christian Wiman has written eloquently about a period of poetic silence. (“Whatever connection I had long experienced between word and world,” recalls Wiman, “whatever charge in the former I had relied on to let me feel the latter, went dead.”)

Only slightly more troubling than this void is the apparent ease with which others can appear to pump out product. Nothing is easier to counterfeit than a lyric poem. You don’t need facility with a fretboard, and you don’t need to know your way around a camera or a palette. You don’t even need stationery—just memory, really. The barrier to attempting lyric poetry is so low it’s basically asphalt. Platforms for the stuff are plentiful, and rotten poems, furred with hyperlinks, abound. What’s more, there’s no critical mass of unsparing critics to help readers sort through the glut. When I would see what was being venerated, I almost always felt discouraged. So, I put a pin in poetry. I’d been composing lines since the 1990s, and anyway, I told myself, I wanted to focus on reviews and essays.

Four years of avoiding the void went by. But in 2017, I stumbled on a workaround: I would write poetry but in the service of a story. I would write a long-ish narrative in heroic couplets. (I’d been admiring Nabokov’s kayfabe verse at the start of his novel-in-endnotes Pale Fire.) A long-ish narrative meant I wouldn’t have to start over every morning. On waking, there would already be poetry to work on because there would be a story to advance. And the heroic couplets meant I would always have a rhyme scheme to complete. (Free verse is an abyss of options; a rhyming couplet, a rope bridge across the darkness.)

Four years of avoiding the void went by. But in 2017, I stumbled on a workaround: I would write poetry but in the service of a story. I would write a long-ish narrative in heroic couplets. (I’d been admiring Nabokov’s kayfabe verse at the start of his novel-in-endnotes Pale Fire.) A long-ish narrative meant I wouldn’t have to start over every morning. On waking, there would already be poetry to work on because there would be a story to advance. And the heroic couplets meant I would always have a rhyme scheme to complete. (Free verse is an abyss of options; a rhyming couplet, a rope bridge across the darkness.)

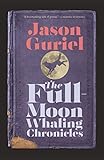

The workaround worked. In 2020, my first verse novel, Forgotten Work, appeared—and drew the most readers I’d ever had. Last summer, a second book set in the same futuristic world, The Full-Moon Whaling Chronicles, came out. Each book busied me for about three years. And each morning when my iPhone went off, there was something to do: a character to describe, a scene to set, a couplet to complete. Take that, void.

The workaround worked. In 2020, my first verse novel, Forgotten Work, appeared—and drew the most readers I’d ever had. Last summer, a second book set in the same futuristic world, The Full-Moon Whaling Chronicles, came out. Each book busied me for about three years. And each morning when my iPhone went off, there was something to do: a character to describe, a scene to set, a couplet to complete. Take that, void.

What’s more, abandoning the short poem liberated me from my own consciousness—and from the de rigueur ruts and rote moves of the lyric poet thinking about grandpa’s photos or fallen leaves. No self-expression for me; I had a plot to unpack and characters to develop.

To wit: at one point in Full-Moon, 20-year-old Kaye finds herself astride a kind of bike-cum-boat called a “Humpback.” She’s zooming through Tokyo circa 2070. Climate change has left the city flooded but strangely functional:

Soon, she came to crest

The onramp, Tokyo before her, endless

Towers ringed with water as if Venice

Had exploded skyward, buildings taking

Leave of what our eyes can take in, making

Their canals seem modest, more like moats.

Street-level Tokyo required boats,

But elevated roadways were amassed

Around the buildings’ waists: spaghetti cast

In concrete.

I would never have gotten to an image like “spaghetti cast / In concrete” or the idea of Venice exploding skyward if I’d stuck with lyric poetry. My cli-fi conceit had demanded cleverness.

Elsewhere, inspired by Alan Moore’s revisionist work on the comic book Swamp Thing, I place Kaye amid a youth subculture whose enthusiasts implant themselves with plant life:

Elsewhere, inspired by Alan Moore’s revisionist work on the comic book Swamp Thing, I place Kaye amid a youth subculture whose enthusiasts implant themselves with plant life:

A pop-up masque had spread across

The Wood. She’d spotted Floras filmed with moss

And ivy. Forking branches topped some heads

Like antlers. Thick vines fell in ropey dreads

Across bark-roughened backs. The leaves of leeks

Stood still on pallid scalps. One “he/him’s” cheeks

Had broken into baby’s breath, the girl

Beside him ballerina-ed with a twirl

Of large, translucent petals at her tiny

Waist: a tutu. Heavies went for spiny

Implants: cactus shit.

The needs of narrative—and a fantastical narrative to boot—unlocked all manner of peculiar language (“pop-up masque,” “ballerina-ed”) and unanticipated metaphor (“ropey dreads,” “tutu”). Over the course of writing two science-fiction verse novels totaling about 600 pages, I felt myself leveling up—and leaving lyric poetry behind.

The needs of narrative also kept me moving and helped me avoid certain sand traps—the selfie-stickiness, the passages that start to skew purple. A professor of mine once pointed out that the beautiful closing paragraph of James Joyce’s short story “The Dead,” the final number in his collection Dubliners, works in part because Joyce has shown restraint: He’s saved the poetry—“the snow falling faintly through the universe” bit—for the end of the book. Lyrical moments, I learned then, have to be earned. (My meditation on love in The Full-Moon Whaling Chronicles arrives on page 364, just before the epilogue.)

The needs of narrative also kept me moving and helped me avoid certain sand traps—the selfie-stickiness, the passages that start to skew purple. A professor of mine once pointed out that the beautiful closing paragraph of James Joyce’s short story “The Dead,” the final number in his collection Dubliners, works in part because Joyce has shown restraint: He’s saved the poetry—“the snow falling faintly through the universe” bit—for the end of the book. Lyrical moments, I learned then, have to be earned. (My meditation on love in The Full-Moon Whaling Chronicles arrives on page 364, just before the epilogue.)

I still read the odd lyric poem. I’m always here for an amazing new Bruce Taylor piece, whenever he deigns to deliver one. And I always inspect with great interest the latest products by A.E. Stallings, Daniel Brown, Michael Lista, Christian Wiman, Luke Hathaway, Carmine Starnino, Robyn Sarah, Mark Callanan, Alexandra Oliver, Evan Jones, and a handful of others.

But the resources of poetry—rhyme, meter, metaphor, simile—seem to me wasted on most of the page-long poems that fatten all those unread literary journals boxed in your garage or that dwell on the other end of the hyperlink in your feed. Verse novels—oriented outward, with the aim of entertaining their readers—have the potential to reach a readership that doesn’t typically mess with poetry.

“Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion,” writes T.S. Eliot in one of his most iconic essays, “Tradition and Individual Talent,” from 1919, “but an escape from emotion; it is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality.” My eyes had rolled over this line many, many times, but I’d never really understood it until I embarked on my verse novel adventure. Bang out hundreds of pages of rhyming couplets about something other than your identity or your perceptions, and you, too, will likely fall out of love with lyric poetry. You will certainly fall out of yourself. You might even land somewhere new.