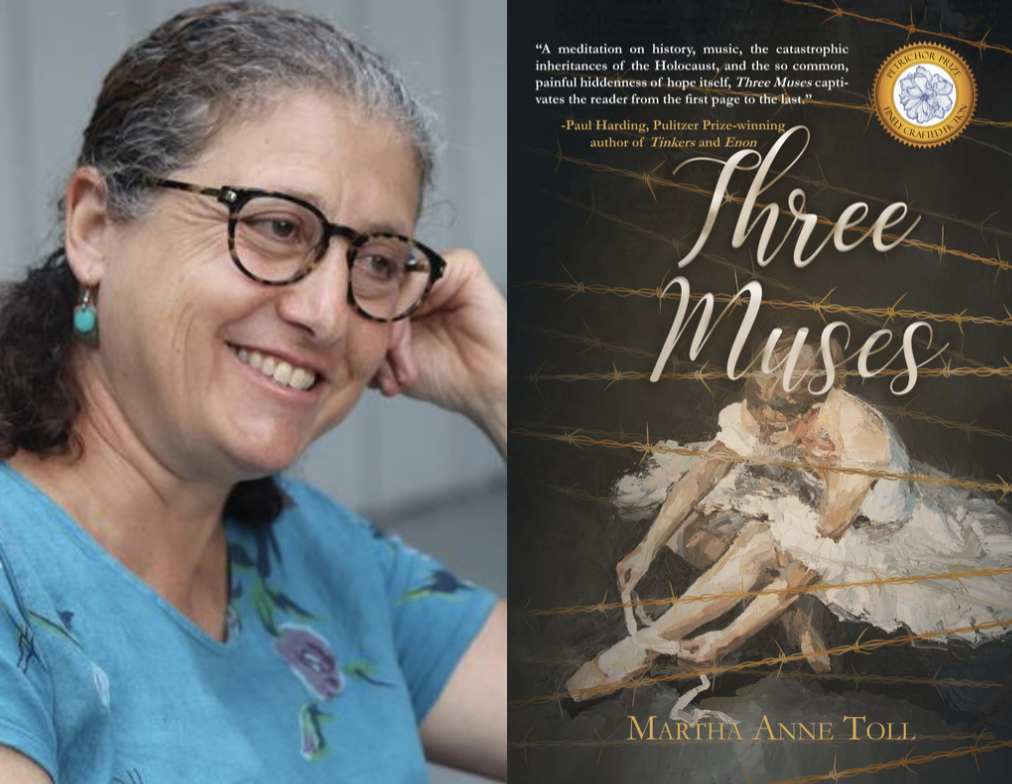

Martha Anne Toll’s debut novel, Three Muses, published today by Regal House, centers on prima ballerina Katya Symanova and psychiatrist John Curtain, whose love story is troubled by each of their fraught relationships with the past. After losing her mother at a young age, Katya hands herself over to relentless discipline and a manipulative partnership with her choreographer, all in pursuit of balletic excellence. John, who was forced as a child to sing to the kommandant of the concentration camp that murdered his family, helps patients but struggles to confront his own past and tainted connection to music. Throughout, the novel and its central love story are inspired and animated by the Greek Muses of Song, Discipline, and Memory.

A professionally trained violist and lifelong ballet devotee, Toll brings her passions to bear on this sweeping tale of music, memory, discipline, and loss. Debuting at 64, after a career dedicated to social and racial justice, she also brings earned wisdom to the human complexities she explores. This is her first novel, but not her first rodeo. Her fiction and essays appear in a wide variety of journals, and her book reviews and author interviews appear regularly in The Millions, NPR Books, the Washington Post, and elsewhere.

Jody Hobbs Hesler: Let’s start with your inspiration. Can you walk us through the Muse origin story and how these Muses shaped your novel?

Martha Anne Toll: In 2010, I was casting around for a framework for a new novel. Browsing the internet, I discovered the three Muses who were part of the mythology on the Greek island of Boeotia: Song, Discipline, and Memory. I conceived of the character of John—saved and damned by his singing—as loosely affiliated with Song; and Katya with her commitment to ballet as loosely affiliated with Discipline. As I refined drafts, I used language associated with Song to describe John, and language associated with prayer and Discipline to describe Katya. Memory exerts tremendous power over both Katya and John. They are burdened with Memory, but they draw solace from it as well. In Katya’s case, Memory holds the key to her future.

JHH: John and Katya both carry such heavy pasts. Could you speak more about how memory shapes them?

MAT: Trauma is ongoing. For many, it’s necessary to plumb traumatic memories and address them head-on. That is certainly the case with John, a Holocaust survivor. John’s role as a psychiatrist is to help his patients investigate their own memories in order to heal. Our first 18 years—our childhoods—contain powerful memories. As we get older, we may interpret or understand those memories differently. I believe we have to reach a certain age and emotional stamina to handle some memories. That is the case with Katya. She has to grow up before she can handle the truth about her mother’s death. As for John, he would prefer not to remember any of his trauma.

It was common in the camps for people to be desperate to have someone to bear witness. People hid messages in the mud and tried to find other ways to share the horrors of their experience. Bearing witness to that level of trauma and genocide is essential. It is another form of expressing collective memory. As Jews, we have been around for 4,000 years and have been dispersed for thousands of years. We are still being dispersed. Our collective memory holds us together.

JHH: Music and ballet have been formative passions in your life. Can you share some of that background and some of the joys and challenges of translating those passions into the mechanics of story?

MAT: I fell in love with ballet when I took my first class at age four. I worked and studied, but truly had no talent. But I had the immense privilege of watching professional dancers rehearsing throughout my childhood and attended as much ballet as came to my hometown of Philadelphia. I became very serious about viola when I began taking lessons at age 14. My teacher, Max Aronoff, was in the first graduating class at the Curtis Institute of Music and helped found the Curtis String Quartet. He deconstructed how to get the richest sound out of an instrument that is unwieldy and large. He also had a gift for teaching bowing technique.

When I turned my attention to writing, my primary challenge was to get these two transitory and ephemeral artforms onto the page. I think that that will remain a lifelong challenge. I had three goals: to convey the total immersion necessary for a dancer or musician to learn their craft. There are no “overnight successes”; it is work, work, work, even for the most talented artists. Second, I wanted to convey the euphoria that comes with “nailing it,” as well as the frustration and rarity of attaining that. And third, I wanted to share the joy of the audience experience.

JHH: The ballets in Three Muses exist only in your novel. What were some challenges, and rewards, of inventing and choreographing original, yet utterly imaginary, dances? How did you choose the music, “map” the dance sequences, and translate it all into words on the page?

MAT: In early drafts, I used well known ballets, such as Swan Lake, and tried to write the story around them. After a couple of drafts, I realized I was too constrained by “real” ballets, so I began making up my own. I didn’t so much “map” out ballets as offer a taste of them. I used my background in music to research and consider what selections would mesh with the particular section of the story. I put a lot of time into choosing titles for the ballets, so that those, too, could lend clues to the story. By providing the opening dance steps and a window into rehearsals, as well as a sense of the music’s mood, I felt—and hoped—that the reader would fill in the rest.

JHH: John and Katya are so driven and determined that their passions sometimes compete against their desires. We want them to choose joy, frivolity, love, and fun sometimes, but we know they’ll suffer for what they’d sacrifice in the bargain. Can you talk about that tension?

MAT: You’re right about the tensions: John and Katya have these tensions on steroids! Katya is someone whom I could never be—her single-minded devotion to dance is something I endlessly admire but could not have done myself. Although she represents an ideal for me, I worry about her tendency to foreclose opportunities for love. For me, these same professional and personal tensions cause work-life balance issues every day. I think they are magnified for women, and that much more magnified for women who strive for the pinnacle of a very rarified artform.

John suffers from a different set of tensions. He feels enormous pressure to succeed in America because he is the only one of his family who survived. His own expectations drive him forward. And as a refugee, he finds it difficult to get fully comfortable in American culture and with American romantic ideals. His early relationship with Ann, the office secretary, is meant to show his awkwardness with his adopted country. For all these reasons, including the violent, early loss of his family and his destroyed childhood, he has unrealistic expectations about love. He falls in love with a mirage—a prima ballerina on stage—and has little inclination to check his fantasies, despite his psychiatric training.

On the other hand, I believe deeply in the power of love and am interested in its many facets, including when singular passion and drive can be detrimental to partnered love, which is ultimately what I’m exploring in Three Muses.

JHH: Your own interests and identities often overlap with those of your characters, so I wonder if you’d like to share any personal or family stories that may have helped inspire their conflicts?

MAT: I knew and am related to people who survived the Holocaust. There is a kind of osmosis when extended family members have German or Polish accents and come to Thanksgiving with numbers tattooed on their forearms. With virtually no formal Jewish education, the Holocaust was in many ways my introduction to Judaism. My father was a WWII vet and was wounded in the early days of the Battle of the Bulge. The war was a consuming interest for him. My mother’s cousin was from Mainz, Germany—the inspiration for John’s boyhood home—and lost her family in Auschwitz. Her unsuccessful struggle to get her father and sister out of Germany haunted her for the rest of her life. She wrote an autobiography for the family that helped me understand the extent to which Jews were fully assimilated into society. Their life in Germany was like Jewish life in America: exclusion, expulsion, and mass murder were inconceivable. To paraphrase the historian Peter Gay, he did not know he was Jewish until the Nazis came to power.

As to the inspiration for Katya, she came fully formed into my head. I very much understand the struggle for mastery of an artistic discipline: as a child, I watched dancers practice incessantly. I trained to be a professional violist and am close to many professional musicians. Artistic immersion was a formative part of my youth and young adulthood. There are many parallels between the pressure and disappointments and perseverance in music and those in ballet.

JHH: Researching the Holocaust, and the very specific roles like the one John had in the camps, of singing for the kommandant, must have been harrowing, to say the least. How did you pace yourself? What were some things you learned that didn’t make it into the book but that you wish people still knew?

MAT: I’ve read extensively about the Holocaust since my early teens. Copious memoirs and historical accounts helped me imagine what it must have been like for John, even though none of us can really understand it. But in my zeal to understand as much as I can, I’ve immersed myself in this material without regard to pacing. I feel compelled to take in whatever I can, no matter how harrowing.

It has been an immense gift to know people who survived, and to listen to their stories and wisdom. But this is the exception. A common fallout from trauma is silence: there is not only pain, but shame and survivor’s guilt. As I got older, I started asking a lot more questions and seeking out more details from friends and acquaintances whose parents and grandparents were Holocaust survivors. It helped me get away from generalities, and think about specific people and specific lives, which is what I tried to create with John. Some of the stories seeped into Three Muses, and others came from my imagination, which was grounded in research. Of course, many things got left on the cutting room floor. For me, the most important lessons are that the Holocaust can happen anywhere, anytime, and so we must guard against any kind of bigotry and racism; and that there is very rarely closure for the victims of such an experience.