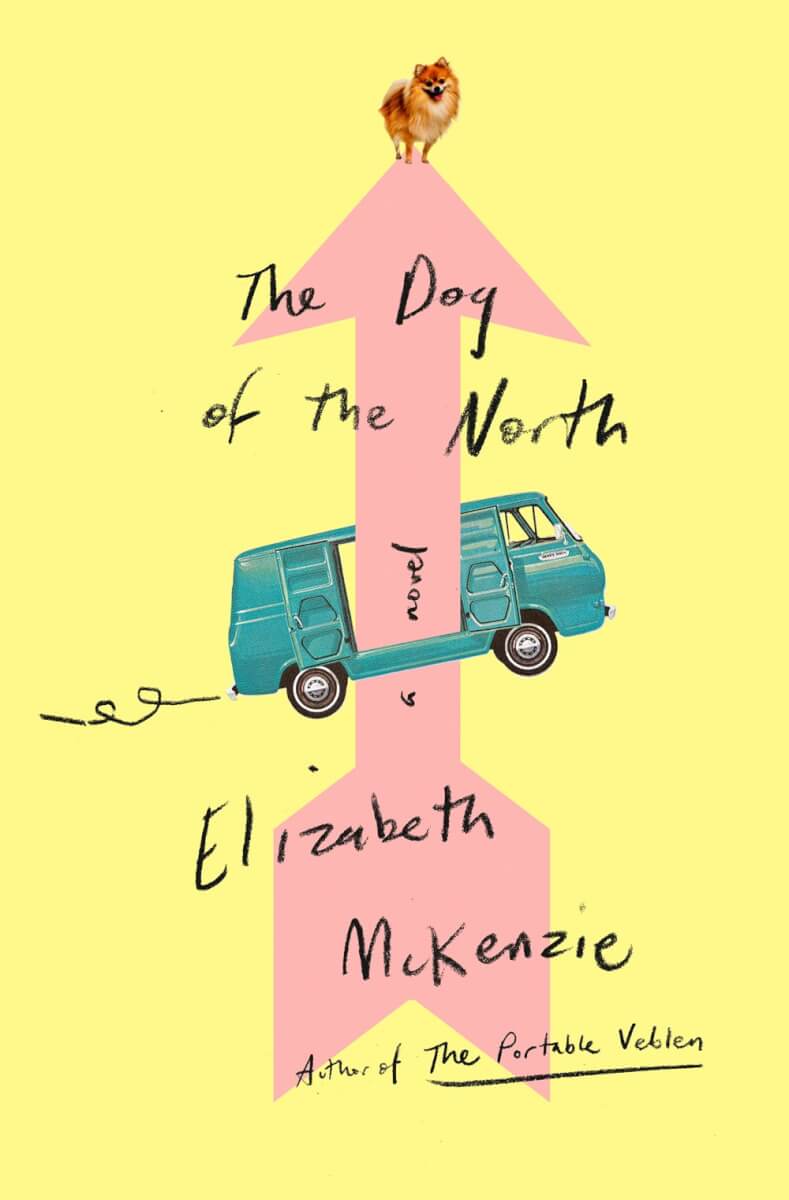

Elizabeth McKenzie’s latest novel, The Dog of the North, is intoxicating fun. The story follows Penny Rush on her quest for a fresh start, which she kicks off with plans to mitigate the hoarding situation created by her prickly grandmother, Pincer. Pincer’s accountant, Burt, offers assistance and also the use of his old van, the titular Dog of the North, which comes with gingham curtains, a piñata, and stiff brakes. Burt and his brother Dale prove decent sounding boards for the tough questions that Penny faces—like why is a detective investigating her grandmother?

I had a chance to talk with McKenzie over email about men both pushy and kind, the function of absent characters in fiction, and writing about repression.

Jen Bannan: As with your last novel, The Portable Veblen, your protagonist has this dogged determination to do right, but also a sense of systems at odds with her personhood. In Veblen it was the military-industrial complex, and in TDOTN it seems to be the patriarchy. Penny Rush’s absent and mentally ill father insists—to the point of harassment—that she call him “Dad,” though he has none of the qualifications of fatherhood except the initial biological one. I wondered if this came from some reaction to some of what was going on during your writing of the book—the #MeToo movement for example?

Elizabeth McKenzie: I hadn’t thought of it that way before actually, but that’s a really interesting take. I wrote that part out of personal experiences with a mentally unbalanced father. Because he was so disabled by his issues, I never thought of him as representing anything other than himself. I might feel differently if he’d been the primary male figure in my life. He wasn’t.

JB: You’ve also written a complex, maddening character with Pincer, the physician grandmother whose chaos has set Penny’s mission in motion. Every time I wanted to decide Pincer was merely wicked, something would reveal a deeper side to her story. Where did her character come from?

EM: I’m glad you noticed the somewhat camouflaged redeeming qualities in her character—particularly her strong feelings about the atomic victims in Japan. My grandmother was involved with that in Nagasaki, and I’ve written about her before in Stop That Girl; she’s the one who hijacks her granddaughter’s meeting with Allen Ginsberg. In the sense that I have a lot of material and feelings about a person like Pincer, and a lot to untangle from personal experience. She basically demands that I write about her.

JB: Although we don’t see them in the present day of the novel, Penny’s long-lost parents and her ex-husband Sherman figure prominently in the story. How do absent characters serve fiction?

EM: For me, the absent character is a way to engage with an emotional vacuum and represent the open-ended nature of many relationships that don’t necessarily wrap up neatly. Something has been left unresolved, and there can be regret. The missing or absent person takes on a mythic quality as well, and without the evidence of their presence, they can be seen as the projections of the characters who remain.

JB: There’s an echo from your earlier work in which Penny has a talent for delayed gratification, and she holds back a lot of her feelings—which is also the case for many characters in your earlier work. I think of her description of the goodbye emails she sends to her ex and her boss: “They were the whimper rather than the bang at the end of my world, but I could not move forward if I were to permit myself the full brunt of my feelings.” Seeing as this is a trait shared by quite a few of your characters, do you think this kind of repression is caused by one’s background or are there more universal forces at work?

EM: You’re on to something here. I do tend to be drawn to characters who hold back, who may be repressed in some way, who are inarticulate sometimes when they should be speaking up and who may get in their own way. I want to coax this kind of character into revealing themselves gradually, maybe overcoming obstacles to do so. This kind of slow metamorphosis in character development is perhaps something I’m most interested in.

JB: Penny also forms a relationship with Burt’s van, the Dog of the North. With all its eccentric accessories it feels like a symbol of newfound freedom, possibility. What other meanings does the van hold for you?

EM: When we find out what the Dog of the North represents to Burt, which has to do with a certain quixotic optimism about the future, I think it might be possible to understand how Penny would be touched and inspired by that. And despite its ragged appearance, you might say the van ends up being a true haven for her in times of trouble. So thematically it’s worth noting that appearances can be deceiving. A man who initially looks like a hedgehog might end up being a gem. Did you know there’s a word for hedgehog-like, and I didn’t know it until recently? Erinaceous! I could have used it in the book!