Of the more than 50 novels H.G. Wells wrote in his lifetime, The Island of Doctor Moreau, published in 1896, is one of his most intriguing—and frightening. This seminal science-fiction narrative tells the story of Edward Prendick, who finds himself shipwrecked on the island home of Doctor Moreau, where Moreau has created human hybrid beings via vivisection, or surgical experimentation on live animals. A compelling page-turner, the novel also confronts major philosophical themes about human identity, our responsibility to animals and other people, and our penchant for playing god.

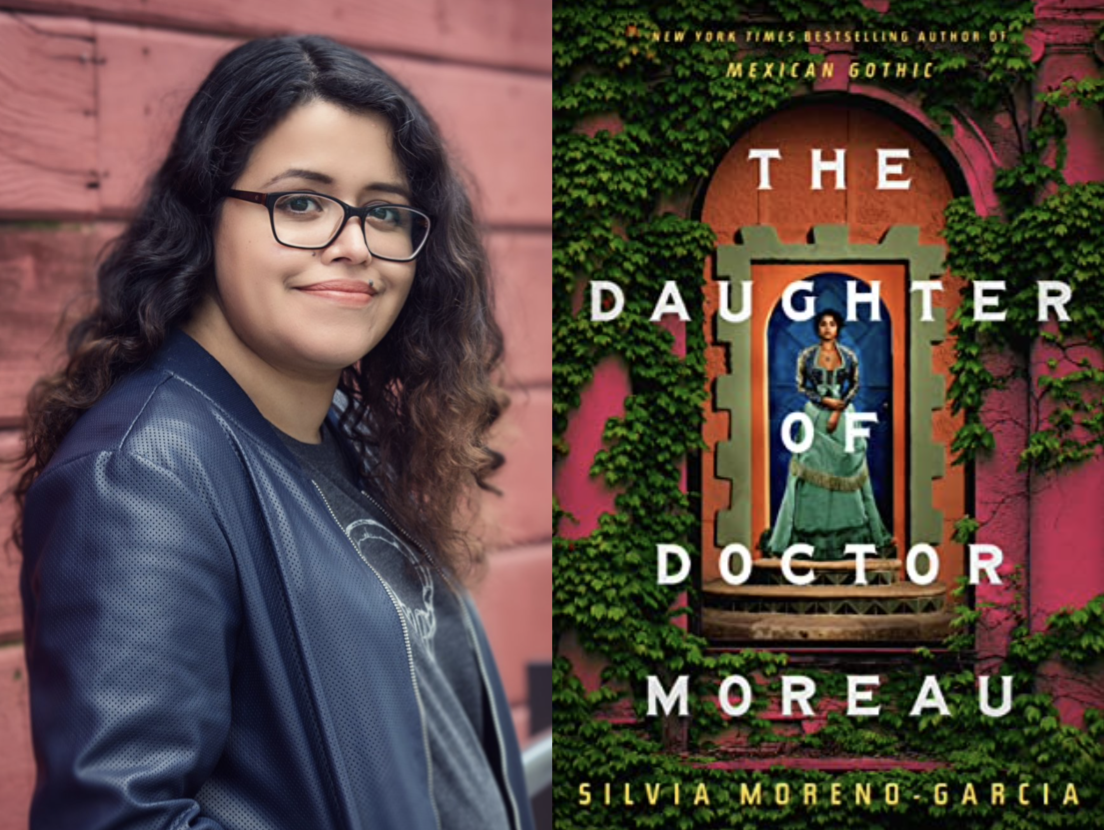

The Island of Doctor Moreau ignited the imagination of bestselling novelist Silvia Moreno-Garcia, whose latest book The Daughter of Doctor Moreau, plumbs even deeper into its predecessor’s philosophical themes by exploring cultural, political, and sociological issues that arise from colonialism, colorism, classism, and sexism. In yet another twist on Wells’s narrative, Moreno-Garcia sets her novel Mexico and centers much of it on Moreau’s hybrid beings.

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau is a thrilling, complex, and ingeniously crafted novel that explores not only what it means to be human, but also society’s often cruel and devious attempts to dehumanize those who are categorized as “other.” Moreover, Moreno-Garcia is an expert storyteller who populates her exhilarating tale with complex characters. I talked with Moreno-Garcia about the evolution of science fiction, the surrealism of history, and writing one of the must-read novels of 2022.

Daniel A. Olivas: Your novel is loosely inspired by the H. G. Wells science fiction classic, The Island of Doctor Moreau, first published in 1896. What was it about the Wells novel that inspired you to create your own vision of Moreau’s medical experiments of creating human-animal hybrids?

Silvia Moreno-Garcia: I’d been interested in doing something with this for a while, but I just couldn’t find a way to ground it. It wasn’t until I decided to set it in the Yucatán in the late nineteenth century that I was able to get a true feeling for the structure of the story. One of the things that interested me about Wells is that he is one of the progenitors of modern science fiction. He helped the genre take shape, but the genre is still very malleable. He wrote what were then called “scientific romances”—the term “science fiction” hasn’t been coined yet. And a lot of the tropes and the forms of the genre that we’ve come to rely on, they’re still in the future. Because of this, I think nineteenth-century literature can transcend boundaries. It can get messy.

The other thing is that I was not just looking at Wells—I was also very interested in the work of Ignacio Manuel Altamirano and his 1869 novel Clemencia. This is what might have been termed a “sentimental” novel, a mix between historical and romance. Altamirano wanted to create a new type of national literature, one that was in some sense free of foreign influence. Ironically, Clemencia is very much influenced by Dickens, Scott, and French literature—the book even opens with epigraphs by E.T.A Hoffmann. Still, Altamirano and other Latin American writers were trying to create a different kind of book at this time, something that blends European Romanticism with Latin American specificities. I was looking back at Altamirano as much as I was looking at Wells when I was considering how to build this book. That’s why Clemencia is also mentioned in the novel.

The other thing is that I was not just looking at Wells—I was also very interested in the work of Ignacio Manuel Altamirano and his 1869 novel Clemencia. This is what might have been termed a “sentimental” novel, a mix between historical and romance. Altamirano wanted to create a new type of national literature, one that was in some sense free of foreign influence. Ironically, Clemencia is very much influenced by Dickens, Scott, and French literature—the book even opens with epigraphs by E.T.A Hoffmann. Still, Altamirano and other Latin American writers were trying to create a different kind of book at this time, something that blends European Romanticism with Latin American specificities. I was looking back at Altamirano as much as I was looking at Wells when I was considering how to build this book. That’s why Clemencia is also mentioned in the novel.

DAO: The Wells novel is told in the first person through the voice of a man who is a shipwrecked on the island of Doctor Moreau. However, you constructed your narrative in alternating third-person chapters that focus on several key characters including Carlota, your novel’s titular daughter, who is the central figure of your tale. Could you talk a little about your creative decision to depart from the Wells novel in this and in many other ways?

SMG: Wells basically tells his story in epistolary form. You have someone narrating what happened to him via a manuscript years after the fact. Conversely, I have two points of view. One is Carlota, Moreau’s 20-year-old daughter, and the other is Montgomery Laughton, the doctor’s right-hand man. They provide a contrast. Carlota has grown up isolated in the middle of the jungle, exposed to the outside only via her father’s teachings and books. She is young, naïve, hopeful, and has not seen enough of the world. Montgomery is an alcoholic who works with Moreau because he hit rock bottom. He is 35, cynical, bitter, and has seen perhaps too much of the world. These radically different characters balance each other and serve to complicate the story.

DAO: By setting your novel in Yucatán in the late 1800s and giving agency to Carlota and the other hybrid characters, one could read your novel on two levels. On the one hand, your narrative can be enjoyed as a thrilling science fiction and horror story that keeps the reader turning each page to find out what happens next. On the other hand, your novel may be read as social commentary on colonialism and society’s treatment—and exploitation—of “the other.” Could you share with us your process of developing the key elements of your narrative, and did you have this dual goal in mind?

SMG: I like grounding my work in historical fact because the truth can be surreal. You can’t quite believe the things you find in footnotes. Colonization is an especially interesting subject in Latin America. Did you know, for example, that there were Mormon colonies in nineteenth-century Mexico? That after the American Civil War, ex-confederate soldiers went to Brazil to establish settlements there? Or that there was a bloody conflict between the Indigenous Maya of the Yucatán and the Mexican population of mixed and European descent? This last event, known as the Guerra de Castas, is what I use as the backdrop in The Daughter of Doctor Moreau. It’s a time when Great Britain is supporting the Maya rebels because it benefits their interests in British Honduras and the peninsula is essentially divided in two. This is also a time of great scientific discoveries, and great quandaries. You have the rise of eugenics, you have vivisection, happening at the same time people who are figuring out ways to save lives and stop the spread of diseases. These different forces coming together and how they clash, I think they’re very interesting. You can approach all of this in a completely realist manner by building a historical novel with no speculative elements. Or you can dwell in the wondrous, almost unbelievable nature of it all.