In 1972, San Francisco’s Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system officials commissioned Oakland artist Michael Rios to create a mural at 24th and Mission Streets. Rumor has it that Rios was torn between his passion for art and his loyalty to his community. When BART announced its plans for the station to be built, the Mission’s residents protested fiercely, blaming BART for increasing rents, which would inevitably price out residents. The protests outside the construction site where Rios was painting clearly influenced the piece he created: Rios’s mural depicts a row of giant humanlike figures, ripping a colossal silver train from its tracks.

*

The Mission District of San Francisco has the highest concentration of murals in the world. The history of Mission muralismo, as it would later be known, begins with the establishment of San Francisco’s Latin Quarter in the 1940s and the subsequent cultivation of the Beat counterculture in the 1950s, which laid the groundwork for the artistic and political renaissance of Latino artists. That renaissance gave rise to the community mural movement of the 1970s. Today, the Mission’s walls narrate a turbulent history deeply entangled with violent battles over real estate.

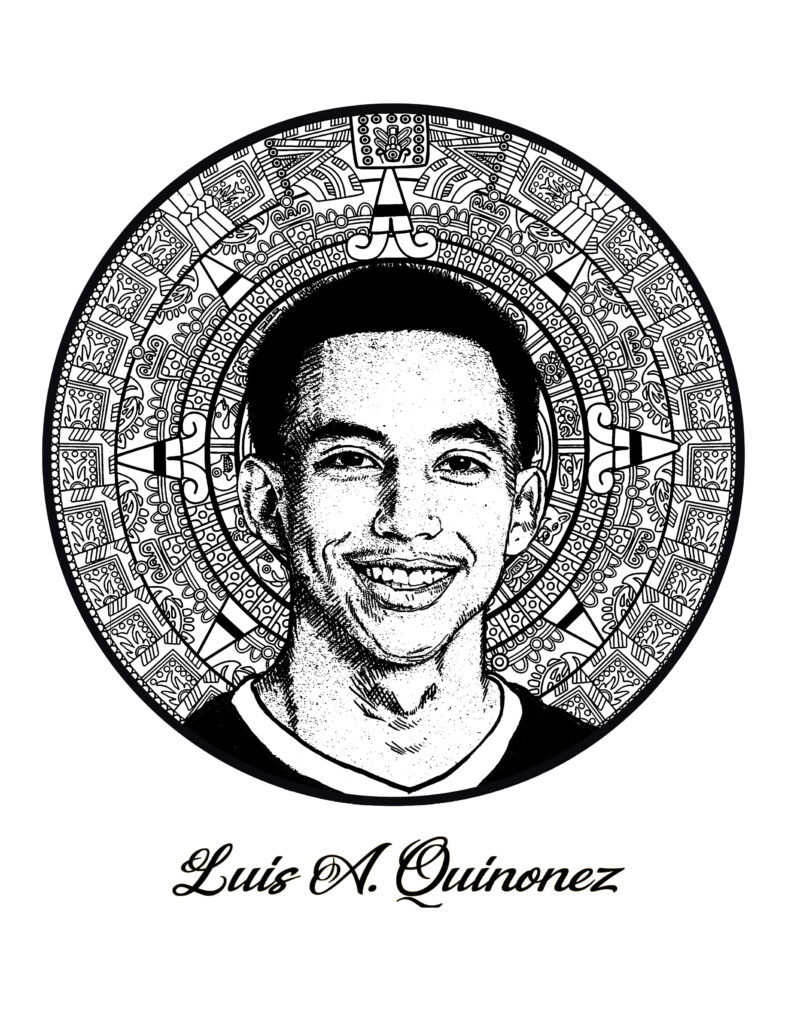

Case in point: in 2019, 19-year-old Luis Alberto Quiñonez—whom everyone called Sito—was shot dead in San Francisco. Sito was my distant relative by marriage; he would not have considered me a part of his life. Still, his death has forced me, an anthropologist whose work focuses on gang cultures, to see murals as the motion pictures of Mission residents’ lives.

Sito’s grandmother, Celia, immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico just as Mission muralismo was becoming a full-fledged movement. In 1978, after traveling to Acapulco de Jurez, where she was raised, Celia returned to the Mission, only to find that her husband, Rene Sr., had moved out. Celia asked around for his whereabouts. He was apparently living on Balmy Alley, a one-block-long alley in the Mission that is home to the most concentrated collection of murals in San Francisco. Alejandro Murguia, a former San Francisco poet laureate, wrote about the murals on Balmy Alley at that time. “Every mural is a challenge,” says Murguia in Street Art San Francisco, “a gauntlet against forgetting, an attempt to recover memory and history—as painful as it has been.”

Entering Balmy Alley, Celia would have strolled past “a popular taqueria, where working men gather late at night under a dim bulb,” as Murguia describes it. As she walked, perhaps, trying to anticipate what to say to her husband, Monsignor Romero, the assassinated archbishop of El Salvador, would have stared at Celia wide-eyed from a garage door. His portrait was only a few yards from Martin Travers’s A New Dawn, a mural honoring the memory of the disappeared in Latin America. Rene Sr. resided at the far end of the passageway, where an enormous figure of La Virgen de Guadalupe faced a South Asian deity. The pair was referred to by locals as “the guardians of the alley.” Next to the guardians, Celia might have glimpsed the spray-painted quotation from W. B. Yeats: “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold.”

Soon after being abandoned by her husband, Celia had a nervous breakdown and was hospitalized. That’s when Rene Jr., Sito’s father, began a cycle of going in and out of foster care. Back then, he looked up to “cholos” whose style was inspired by Mexican gangsters. They drove lowriders with glossy murals of Aztec warriors and Mayan pyramids painted on the hood. It didn’t take long for Rene Jr. to become one of them.

Discussing the history of youth gangs in the Mission, artist Aaron Noble tells a story about the Vatos Mexicanos Locos, a raucous group that claimed Clarion Alley, not far from where Rene Jr. grew up, in the early 1990s. At the time, Noble was considered a “guardian of murals” and would get into arguments with the young Vatos because they had a habit of tagging the street art he cherished. Noble wanted the defacement to stop, so he tried to convince the Vatos to create their own mural. The kids wanted to paint Wolverine from the X-Men.

The Vatos had nearly finished their work when they “suddenly picked a fight” with Noble, which, he told me, “blew up in minutes to a huge screaming match.” Frustrated, Noble retired to his apartment to calm himself. When he returned to the alley later that night, the mural they had all worked on was effaced. Fueled by spite, Noble painted Wolverine. But not how the Vatos wanted to see him. The razor-clawed superhero lay on the ground, sucking his thumb like a baby.

Twenty years later, some of the kids Noble described—people like Rene Jr.—were now anti-gang activists, disciplining today’s youth for the same irrational, petty, and undisciplined behavior that the adults in their lives once accused them of.

In 2006, after a short stint in federal prison, Rene Jr. became the executive director of a gang-prevention organization called Homies Organizing the Mission to Empower Youth, or HOMEY. When he was in elementary school, Sito used to visit his father at HOMEY’s headquarters, at 18th and Mission Streets, on his way home. When Sito was in second grade, he helped local muralists Eric Norberg and Mike Ramos paint a 117-foot mural called “Building Bridges of Solidarity.” Sito colored in the orange and yellow flames of the prayer candles that sat behind a row of marigolds.

The organization had notched some major accomplishments during Rene’s tenure. He arranged a truce between two notorious street gangs, the Sureños and the Norteños. Despite his efforts, however, the truce that Rene worked so hard to forge would be too tenuous to benefit his son.

Emerging from the bowels of the BART station on Tuesday, September 2, 2014, around 1:00 P.M., 14-year-old Sito walked underneath Rios’s dissenting mural. Sauntering aimlessly along Mission Street that day, Sito ran into a few Norteños, some of whom he knew from the neighborhood. The group made the first left, near a liquor store that had another faded mural on its side—this one of a pig-tailed migrant woman strangling a rifled military man. Moments later, a tragedy occurred.

Sito’s companion scuffled with and ultimately stabbed Rashawn Williams, a 14-year-old high-school student from the Mission. The next day, Sito was arrested and subsequently charged with Rashawn’s murder. Fortunately for Sito, his public defender retraced his steps and then found video footage from the McDonald’s on Lilac Street, near an unmistakably psychedelic mural that felt like a hallucination of Hindu gods. The footage made it clear he had not killed Rashawn. The charges were dropped, and Sito was released after nearly five months in juvenile hall. But his problems weren’t over. Not by a long shot.

On September 8, 2019, Sito was murdered by Rashawn’s little brother.

*

On the night Sito died, his mother Beatriz left her house, got into her car, and drove past the Cypress Street Murals, where cartoon video game protagonists, the Mario Brothers, stood back-to-back in a tough-guy pose, arms folded across their chests like rappers. Mario Brothers was the first video game her son ever played with his father.

Around the corner, her headlights reflected a graffitied painting of a dimpled brown boy wearing a black skull cap with a gold halo. According to Beatriz, Sito’s face morphed into his for a moment, and she nearly crashed before reaching Zuckerberg General. But Sito wasn’t there. His ambulance had already transported him to the morgue.

Meanwhile, Rene Jr. mourned his son’s death from his home in Maxwell Park, a quiet neighborhood in East Oakland. The community is known for its mosaics, which adorn local playgrounds, libraries, and even public trash receptacles. Sito always knew he was close to home when he saw a distinctive trash can on his father’s street. An amateur artist had decorated the four sides of the receptacle to depict the process of metamorphosis—beginning with a green worm and ending with an orange butterfly against a blue-tiled sky. It’s fitting, then, that the image that Sito’s family created to remember him by resembles both a mosaic and a mural. In it, the Aztec sun stone of Celia’s heritage serves as a backdrop for Sito’s stenciled face, representing the metamorphic power of art to grieve loss in the wake of despair. I hope one day a muralist of Rios’s caliber inscribes this image of Sito in the Mission’s gritty terrain.