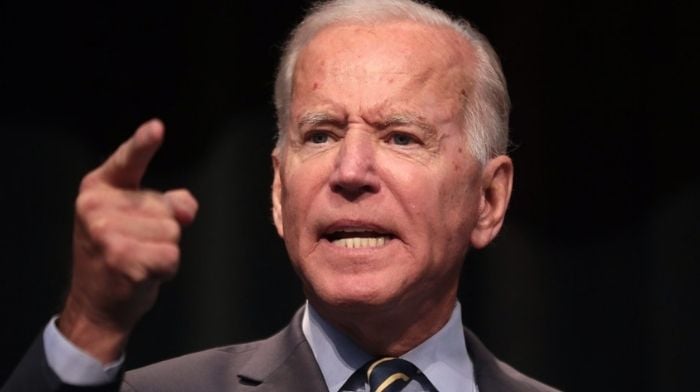

While Dan Sinykin’s department profile says that his work focuses on American literature the second half of the twentieth century, that limited description obscures the breadth of his analysis in terms of both content and method. His most recent book, Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature (Columbia 2024), describes the history of what he calls “the conglomerate era,” running from roughly 1960 to the present. Bringing together economic and cultural history, public statements from publishing executives, private correspondence between authors and agents, advertising materials, close readings and literary scholarship, he argues that changes in the ways that literature was acquired and distributed during this period affected the way that novels were (and are) written. The result was the emergence of “conglomerate authorship,” a process that shapes not only the formulaic romance novels of Danielle Steel, but also, Sinykin argues, the literary fiction of authors like David Foster Wallace and Toni Morrison.

Outside of his work within academia, Sinykin is an active contributor to a variety of public-facing venues. He has worked as an editor at Public Books and Post45, and published in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Dissent, and The New York Times. He is also an undeniable star of academic Twitter, shifting with ease between earnest intellectual debate, incisive commentary on the state of the discipline, and a menagerie of observations, memories, and non-sequiturs.

I talked with Sinykin during his recent visit to UNC–Chapel Hill, where he was giving a talk as part of the Critical Speak Series hosted by the Department of English and Comparative Literature.

Brendan Chambers: To begin, I’d like to speak about how you arrived at the thesis for Big Fiction. Did you begin by noticing shared formal features and thematic concerns in the novels of this period and then move to historical research to try to explain their cause? Or was it vice versa? Or perhaps something in between?

Dan Sinykin: It’s a real hermeneutic circle. There is lots of moving back and forth, shuttling over and over again between the particular individual readings and larger scale patterns, and then recursively iterating on theses.

I’d say as early as 2013 or 2014, when I was still a graduate student, I started to wonder about American literature more systematically—what was structuring it, what the world of economics was doing to the aesthetics of the novel—and that got me interested in publishing. And when I was looking at what people had said about the publishing industry, there was a pretty reductive argument in two directions. Either conglomeration has been really bad for literature, it’s ruined literature, or actually conglomeration has infused the field with capital and writing has become a lot more diverse. In the early research, I just kept encountering these two responses. People had been making these arguments for 45 years, and seemed unaware of the fact that they were repeating the same arguments that had been made decades earlier.

A lot of good literature has continued to be produced over the last 50 years, so the argument that literature has been destroyed doesn’t seem to hold much water, but at the same time the notion that it has been good for literature is one that I approached with great skepticism. So the project from early on was to try to get into the weeds, to get a bit more specific and try to figure out exactly how conglomeration had changed U.S. fiction.

BC: Throughout Big Fiction you frequently weave in anecdotes from your own life as a reader. What was the rhetorical purpose of these anecdotes? Do you feel like the book’s argument has a personal dimension?

DS: So, to be anecdotal about the anecdotes, I’ve heard from a lot of people that those moments stuck out to them and gave them an access point into how they relate to publishing history and American literary history. They allow them to situate themselves and think about how their experiences of bookstores when they were a kid shaped them, and how that ties into publishing history and the kinds of arguments I was making in the book, which was the goal.

That was in part why I did it. Big Fiction is published at Columbia University Press, but from the early stages, my editor, Phil Leventhal, and I talked about wanting to try to make it a trade crossover. Which is a tricky, perilous task. But bringing in those personal anecdotes was one technique we used to try to signal that this book could invite people in who were not academics.

I’ll also add that one inspiration for including personal anecdotes was Janice Radway’s scholarship—she does the same thing. She talks about her own experience as a reader growing up, and how she felt alienated from the norms of reading that she encountered in grad school. We have different histories of personal reading, but I found that to be a very powerful move, and something that stuck with me long after reading Radway’s work.

BC: Were there any archives in particular, or interviews, that you felt individually moved the project forward in a significant way? Or was it more a slow process of accretion?

BC: Were there any archives in particular, or interviews, that you felt individually moved the project forward in a significant way? Or was it more a slow process of accretion?

DS: The temporality of the archive is uncanny. Anyone who has spent a lot of time in archives will know what I mean. You go in and there’s this kind of ritualistic feeling, signing in, going to the reading room. I spent a lot of time at Columbia University, where they have tons of publishers’ archives—most important to me, the Random House Papers. I would travel there for a week at a time and go through these documents, and I would just get into these flow states where time would disappear. I’d look at my watch and it would be two hours later in an instant.

Reading these archives meant learning in a kind of skimming form. You gradually, incrementally pick up important details. Names that were completely meaningless to you at first start to take on significance. You start to build a sense of who this person is, and then suddenly you come across a document and it’s like, “Oh wow!”

For example, there was a day I was coming across all of this sexist correspondence from Bennett Cerf, the co-founder and longtime president of Random House. One of the chapters in my book spends a lot of time looking in to the sexist culture of Random House, so finding all of these documents—not just Cerf’s, though his are the most outrageous—was a sudden cache. It substantiated the hunches that I had about the office culture at Random House in the 60s and 70s.

BC: How do you view the relationship between your public-facing work and your work in academia? Do you feel that is a useful distinction to draw?

DS: It is a useful distinction. The work I publish in peer-reviewed journals is principally read by academics. Work I publish in public-facing venues is read by both academics and others. There’s a vibrant community of literary critics outside of the academy who read one another’s works. Ryan Ruby is one who’s been at the forefront of fostering dialogue between academics and people who are critics outside of academia. Those two worlds exist separately, but they’re also in conversation.

Different public-facing venues each have their own relationships to the academy. Public Books, for example, publishes pieces that have reach outside of academia. However, the principal readership is within the academy, though pieces may reach people in other disciplines who don’t normally read your work. If you write for somewhere like The Nation, you are going to be principally writing for people outside of academia. Even in public-facing venues, there is no one public.

I derive a variety of benefits from public writing. One is the affordances and limits of working on a different time scale. Writing a peer-reviewed piece, you might start working on it, get it in a state where your friends or colleagues can read it, get it in a state where you can submit it to a journal, and by the time it goes through peer review, the whole process—if you’re lucky—takes three years. It can easily take five. With a public-facing piece, someone can commission something from me, I can write it and have it out in the world in three weeks. It’s great for starting conversations. You can test out ideas that you’re working on for your scholarship and get feedback on them. But those different time scales translate to differences in longevity. Peer reviewed scholarship will take longer to be received, but it will last. You might have people picking up your work in 10, 20, 30 years. Public-facing work, by contrast, tends to have a pretty short lifespan. It can be as short as 24 hours.

There has been a considerable shift in collective attitude towards public-facing work since I had my first run on the job market in 2014. By the time I got a tenure track job in 2019, even in those six years there was a major change in attitude towards public-facing writing. When I started on the market people would warn you that you might not be taken seriously if you were publishing in the LA Review of Books or Public Books alongside your peer reviewed scholarship. In 2019, and certainly now, people have largely recognized that that’s silly, and that there’s a lot of really important, valuable public-facing work to be done. But we still lack an institutional mechanism to recognize that value; none of my public-facing work counts in the same way that my peer-reviewed stuff does.

BC: You’re a big presence on academic Twitter with a recognizable and often hilarious voice. Where does your Twitter persona come from? What do you like about academic Twitter? What do you hate about it?

DS: Oh, man. [laughs] Academic Twitter is something of a compulsion for me. My wife hates it. [laughs] I love it for a few reasons. I think it’s a very funny place. I can go there and get a laugh almost every day from someone like Nate Wolff or Katie Kadue or David Hollingshead, it just makes me happy to read them. It’s a venue for me to put out my own sort of performance art. You know, I get to create and toy with a persona which I’ve always enjoyed. I was something like a class clown in high school and college. Ultimately, it’s kind of a playful space that I try to bring some levity to.

But Twitter also serves as a medium for intellectual engagement in a way that I find really satisfying and productive. I learn things. I get into arguments with people. I debate. It’s a form of intellectual community. I really value it and would feel it a true loss if Twitter were to completely implode.