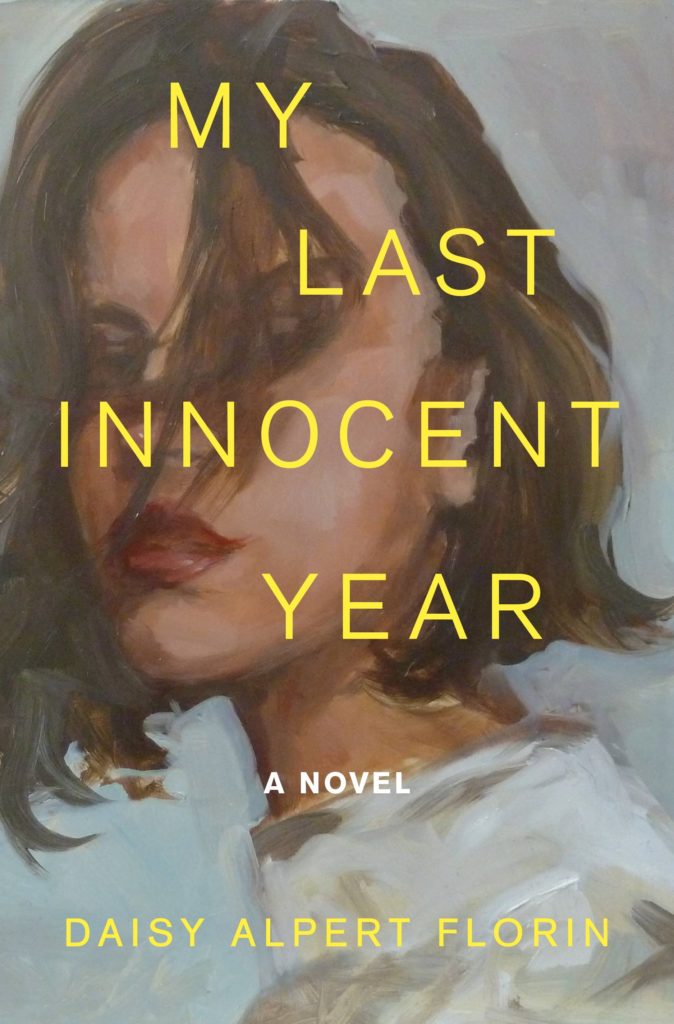

Daisy Alpert Florin’s debut novel, My Last Innocent Year, is a rewind to the late ‘90s. Our protagonist, Isabel, is a young Jewish woman from New York pursuing a creative writing degree at a prestigious liberal arts college in New Hampshire. After Isabel is assaulted by a peer at the start of her last semester, she confides in her roommate, Deborah, for support, only to find that Deborah isn’t willing to let this incident go without taking punitive measures. Meanwhile, Isabel’s creative writing professor, Connelly, begins to express an interest in her that goes well beyond her short stories, resulting in a secret relationship rife with questions about consent.

But even that description is colored by my personal read on the book: Isabel herself likely would not say was assaulted; marketing copy for the novel describes the encounter as “nonconsenual.” This distinction ties into the bigger picture questions that dominate the novel: What counts as violence? Whose definition matters? Isabel’s college experience spans the Clinton/Lewinsky years, and when Florin brings reader into the present, our protagonist finds that professor again, only this time, against the backdrop of the MeToo movement.

I spoke with Florin about nineties nostalgia, the intricacies of writing consent, and the unexpected timeliness of her novel.

Marissa Higgins: Your novel is set in the ‘90s. Do you feel like it’s historical fiction? Did the label of “historical fiction” come into your mind when you were writing or revising?

Daisy Alpert Florin: I went to college in the ‘90s, so I think that was just naturally the setting and time frame I wanted to explore. I would be hard pressed to write a novel about a college campus today. I think it’s just so completely different. I think that maybe it was easier for a student and teacher to have an affair before there were a social media or internet or text messages—you know, you could maybe keep secrets a little bit better. I think also having the Clinton/Lewinsky scandal as the backdrop was interesting because we’ve come around on that recently, sort of re-examining what that meant. But culturally, I wanted to go back to the birth of it.

The book is historical in the ways it talks about consent: what is rape and what’s not and how institutions respond to that. I think that’s a really different conversation today than it was back then. And the way that there wasn’t as much of an understanding of the gray areas of consent back then. Whereas today, I think we acknowledge those gray areas, that there can be a lot more nuance to what constitutes consent.

MH: Can you share a bit about how that comes through for Isabel in the novel?

DAF: I think that what happens in the opening chapter with is something she’s not really able to put a name to at the time. Was it rape? Was it an encounter with a guy? She doesn’t really know what to call it, she just knows how it makes her feel. But then her friend Deborah is very quick to give it a label and to call it rape. Which, whether it is or isn’t, Isabel isn’t really sure that that’s the right label. I think historically that might have been how women felt. There was this idea of date rape and they were kind of separated; as I recall, rape and date rape were sort of two separate things.

MH: How does the cultural framework of the time—as you put it, for example, date versus date rape—inform how Isabel responds after the encounter?

DAF: During the scene [where Isabel has a meeting] with the Dean, Isabel really doesn’t want to pursue it. I think a lot of women at that time, and probably even still today, just kind of wanna know: What is justice going to look like for something like this and what is it going to cost her? Especially in a college setting, when you only have so much time to get what you need from the college experience. So maybe you don’t want to spend several months or half a year litigating a thing. And what will justice look like anyway, at the end?

So there’s that piece about consent. In terms of a teacher-student affair, I think we have come around on this in a lot of ways since then. Is it appropriate under any circumstances? Isabel, at the time of the affair [with Connelly], is 21, 22 years old. She’s a consenting adult. Maybe in the seventies they would have gotten married. Now, we kind of look at that in a very different way. Is consent possible when there are power dynamics? When they’re unequal? I think those things have really changed, so I wanted to get down in the muck with those questions and not answer them in a way that felt concrete. I still feel conflicted about all of those questions, so I wanted to stay in an ambiguous place.

MH: Do you think this novel, and discussions of consent, would be different if the novel were set today?

DAF: I think it would be a really different story. When we were going to college in the ‘90s, I don’t think anyone talked to me about consent. At all. That was just not really discussed. And I think even like my mother’s generation, they were just sort of like: That’s how it goes and Sometimes that just happens. I think generationally we’re talking about it more, for sure. Our kids—my kids—have like a lot more information than I certainly had.

MH: What was it like writing a character who is a writer? Did you ever get feedback about how the book is a bit meta, like you’re a woman with feelings writing about a girl who is writing about her feelings?

DAF: I didn’t really think of myself as a writer until I was in my forties. I was always a writer. But I was not an English major. I never took a creative writing course in college. I didn’t identify with writers, you know, people who wrote stories and wrote for the literary magazines. That was never me. A lot of what I’m imagining in the workshop scenes, for example, are things that I experienced in my mid to late forties.

The kinds of workshops you take in your 40s, or workshops with a lot of women—it’s just a very generous and safe space. That was exactly what I needed. I’m imagining what it would have been like if I had gone into those kinds of classes as a younger person, and I think I would have been really shut down. And I think that’s what happens to Isabel where her talent and ambition become sexualized by this professor [Connelly]. I think that can also happen to women like, Oh you’re a great writer, and I also want to sleep with you. It kind of gets muddled there. What I really wanted to sort of come out saying at the end was whether Professor Connelly really does believe she’s a great writer or whether he is just seducing her, she believes she’s a great writer. She takes what she needs from that relationship and ultimately becomes a writer.

MH: I was really drawn to this idea of choosing to believe certain things. Isabel chooses to to see herself as a writer, right? I think it can also apply to things like what we believe about consent; what do we believe about our own experiences. Can you speak to that at all?

DAF: That was a line where Isabel meets Joanna Maxwell [a novelist and creative writing instructor at the college] at a party. Joanna says to her, Oh, I hear you’re really great writer [in reference to something Connelly had said about Isabell’s work]. And then it that typically self-deprecating way, Isabel says, Oh, no I’m not really that great. And Joanna says, You know, you should choose to believe him. That was one of those lines that came to me—I wrote it down and it kept coming back. Once I had that idea in my head, I could see all the ways it played out through the other parts of the book.

When you come to a later point in life, there are certain things you’re just never going to really get an answer on. You’re never going to have clarity on certain things. So at a certain point, you have to choose to believe a certain version of events. You know: I’ll never know the truth about this, about what really happened that night? So I’m just gonna choose to believe that this happened because it makes it possible for me to go on. Things happen to you, but you do go on. Sometimes it has to be an active choice.

MH: Do you feel like coverage or discourse about MeToo impacted what you brought to the book? Or did you feel like the book was more in isolation while you writing it?

DAF: I started writing the book before Trump and before MeToo. I was working on the book already back in 2015, 2016, and then culturally all these things started happening. I was like oh my gosh, the world is talking to my book. It’s like well, I got to write about this. It became such a live conversation between the two time periods. The book was definitely always impacted by what was going on. I think that’s almost why I was able to finish it, because so many things were happening in the culture, I had to keep going with the book. The world was telling me: keep writing this book.