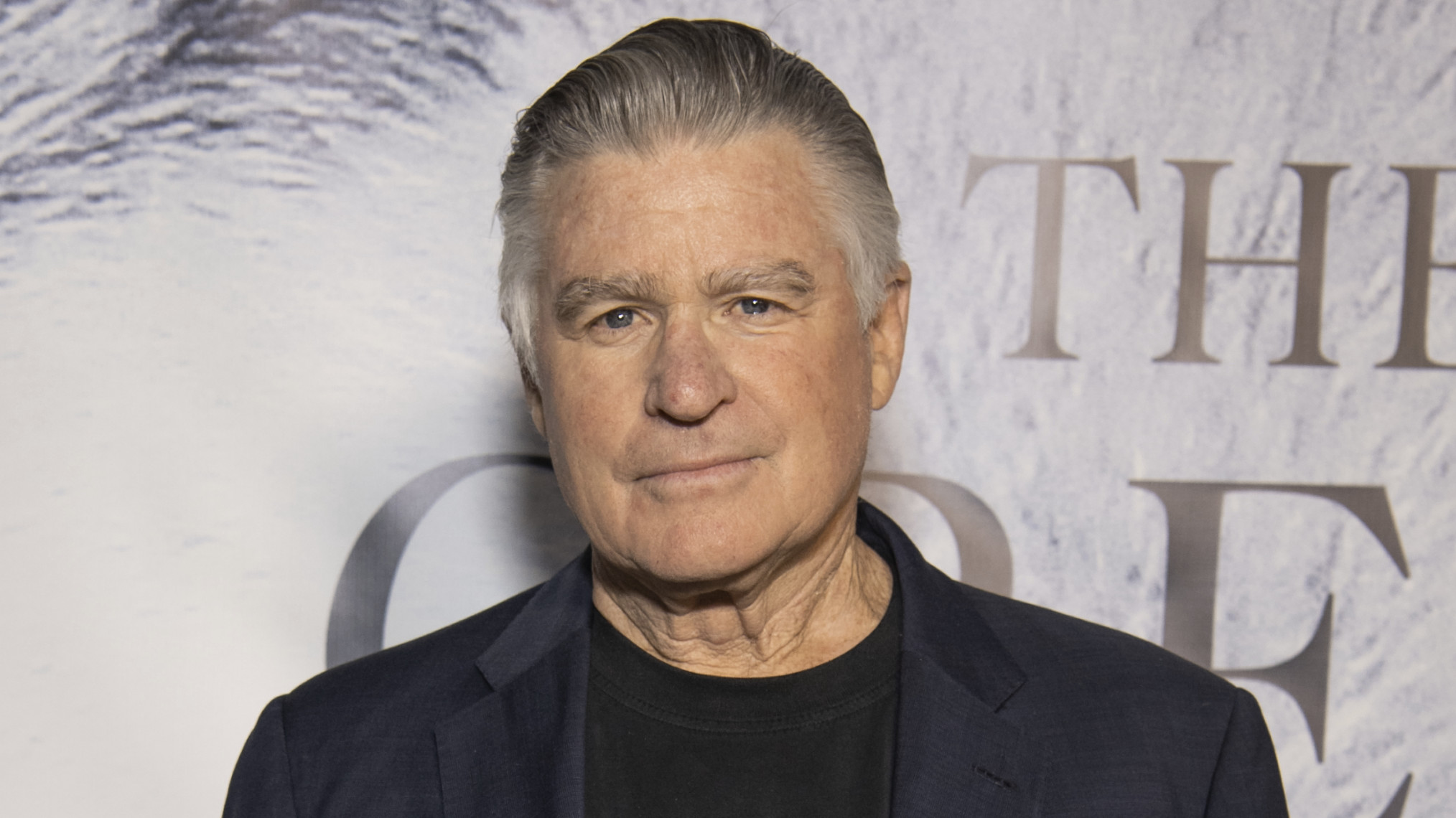

I once invited Martin Amis to play tennis. The year was 2007 and he was visiting Chicago to promote his latest novel, House of Meetings. After his book talk, I lined up with other audience members to get my copy signed, having thought carefully about what I would say to the famous writer. I had read that he enjoyed racquet sports and was vain about his topspin lob. So I slyly asked as he inscribed my book, “Would you care to hit the tennis ball while you’re in town?” He looked taken aback by the question and seemed to give it a moment’s thought. But then he politely demurred, gentler in person than his wicked prose had led me to expect. I shouldn’t have been surprised by his answer. It was the middle of January and about 20 degrees outside.

I once invited Martin Amis to play tennis. The year was 2007 and he was visiting Chicago to promote his latest novel, House of Meetings. After his book talk, I lined up with other audience members to get my copy signed, having thought carefully about what I would say to the famous writer. I had read that he enjoyed racquet sports and was vain about his topspin lob. So I slyly asked as he inscribed my book, “Would you care to hit the tennis ball while you’re in town?” He looked taken aback by the question and seemed to give it a moment’s thought. But then he politely demurred, gentler in person than his wicked prose had led me to expect. I shouldn’t have been surprised by his answer. It was the middle of January and about 20 degrees outside.

As I look back on that ridiculous encounter, I think I know what it was about. I had a sense that receiving a line of fans and hearing the same murmured appreciations must be particularly tedious for Amis. There would be so much repetition of moist sentiment: the same predictable words, over and over. I hated to add to the burden, so I tried to give him a sporting reprieve—or at least, a line he had not seen coming. Amis himself was partly to blame for this youthful impulse. One of his famous rules for writers went, “Try not to write sentences that absolutely anyone could write”; another was, “Watch out for words that repeat too often.” I had simply transposed the advice to my role as queue-stander and audience-member. In this context, the rules meant: don’t be boring. Say something new.

Amis, who died last month at age 73, was never boring. The author of some 25 books, many of them brilliant, he seemed incapable of writing a bland string of words. He describes a newly adopted dog in the novel Money as “a twirling hysteric of gratitude and health.” The North Atlantic in Inside Story “seethed and hissed with hatred and hostility, snarling, sucking its teeth, smacking its chops, as ravenous as wildfire.” “It’s a funny language, German,” Amis muses in Time’s Arrow. “For one thing, everybody shouts it. All those very long words: the literalism, the tinkertoy accumulation. It sounds pushy, beginning every sentence with a verb like that.” His aggressively, hilariously vivid lines poured forth like gold coins from a payout slots machine. They just kept coming.

Amis, who died last month at age 73, was never boring. The author of some 25 books, many of them brilliant, he seemed incapable of writing a bland string of words. He describes a newly adopted dog in the novel Money as “a twirling hysteric of gratitude and health.” The North Atlantic in Inside Story “seethed and hissed with hatred and hostility, snarling, sucking its teeth, smacking its chops, as ravenous as wildfire.” “It’s a funny language, German,” Amis muses in Time’s Arrow. “For one thing, everybody shouts it. All those very long words: the literalism, the tinkertoy accumulation. It sounds pushy, beginning every sentence with a verb like that.” His aggressively, hilariously vivid lines poured forth like gold coins from a payout slots machine. They just kept coming.

While he will likely be remembered for his fiction, Amis was an equally talented critic. That’s how I know his voice best. At the time of our brief encounter, I was a newly minted book reviewer with about a dozen bylines to my name. His collection The War Against Cliché had recently won the criticism award of the National Book Critics Circle, which I had proudly joined as a dues-paying member. With its fearsome title, imposing breadth, and dynamo style, the volume took on an elevated status for me: a manual, a Bible, a vade mecum. Even the table of contents was laid out differently. I regarded it with a similar awe to that which Amis had applied to James Joyce: “Let us look at this prose and its scales of intensity.”

While he will likely be remembered for his fiction, Amis was an equally talented critic. That’s how I know his voice best. At the time of our brief encounter, I was a newly minted book reviewer with about a dozen bylines to my name. His collection The War Against Cliché had recently won the criticism award of the National Book Critics Circle, which I had proudly joined as a dues-paying member. With its fearsome title, imposing breadth, and dynamo style, the volume took on an elevated status for me: a manual, a Bible, a vade mecum. Even the table of contents was laid out differently. I regarded it with a similar awe to that which Amis had applied to James Joyce: “Let us look at this prose and its scales of intensity.”

That’s both an overblown comparison and a dangerous example for a pipsqueak: I was naïve. Writers are readers, and also mimics. I look back at my early criticism and see a kid reaching while overestimating the length of his arm. In those days, I was not merely aping Martin Amis. I also badly mimicked other novelists who shared his endorsement, like Saul Bellow and Vladimir Nabokov. In addition to writing engagingly about literature, Amis displayed fine taste in it, particularly in admiring the great wordsmiths at the level of the sentence and the phrase. With these referrals, his critical judgment shaped me not just as a writer but as a reader. Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March was “a marvel of remorseless spontaneity”; Nabokov’s Lolita was “both irresistible and unforgivable.” While discussing Bellow, Amis taught me a practical lesson when sitting down to assess a masterpiece: “Your job is to work your way round to the bits you want to quote.”

That’s both an overblown comparison and a dangerous example for a pipsqueak: I was naïve. Writers are readers, and also mimics. I look back at my early criticism and see a kid reaching while overestimating the length of his arm. In those days, I was not merely aping Martin Amis. I also badly mimicked other novelists who shared his endorsement, like Saul Bellow and Vladimir Nabokov. In addition to writing engagingly about literature, Amis displayed fine taste in it, particularly in admiring the great wordsmiths at the level of the sentence and the phrase. With these referrals, his critical judgment shaped me not just as a writer but as a reader. Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March was “a marvel of remorseless spontaneity”; Nabokov’s Lolita was “both irresistible and unforgivable.” While discussing Bellow, Amis taught me a practical lesson when sitting down to assess a masterpiece: “Your job is to work your way round to the bits you want to quote.”

He was a bracing critic because he married brilliant prose with total honesty. You had the sense that he was giving you his true, unvarnished reaction to the work under consideration. (Another rule: “usually your first instinct is the right one.”) Amis could be as brutal to books he disdained as he was generous to his favorites. Here is how he appraised a novel by John Fowles: “Mantissa is serious all right, but it permits itself to be ‘deliciously irreverent’ too. There are conundrums for the erudite, but there is also honey for the bears. Most of the book is in dialogue. The dialogue is terrible.” Amis liked pulp, but only up to a point. He read Hannibal, by Thomas Harris, “with much dropping of the head and rolling of the eyes, and with considerable fanning of the armpits.”

He was a bracing critic because he married brilliant prose with total honesty. You had the sense that he was giving you his true, unvarnished reaction to the work under consideration. (Another rule: “usually your first instinct is the right one.”) Amis could be as brutal to books he disdained as he was generous to his favorites. Here is how he appraised a novel by John Fowles: “Mantissa is serious all right, but it permits itself to be ‘deliciously irreverent’ too. There are conundrums for the erudite, but there is also honey for the bears. Most of the book is in dialogue. The dialogue is terrible.” Amis liked pulp, but only up to a point. He read Hannibal, by Thomas Harris, “with much dropping of the head and rolling of the eyes, and with considerable fanning of the armpits.”

Recently I noticed that my copy of The War Against Cliché had grown a little tattered, its spine bleached by the sun. So I treated myself to a fine hardcover edition. As I went back through it this past week, what stood out were the arresting first sentences in many of Amis’s reviews. They usually made me smile, often made me laugh, and never made me want to stop reading. He combined a journalist’s instinct for the bold lede with a novelist’s flair for style. One of my favorites was this opener (reviewing William Burroughs): “If a weak baboon is attacked by a strong baboon it has two means of escape: it can offer up its awful plum-hued rear for passive intercourse or it can mastermind and lead an attack on an even weaker baboon.” Opening strong is another good lesson for a critic. Yet these days, a little older and without as much to prove, I read Amis less with an urge to light the same sort of firecracker myself than a general reminder to liven up the prose. Bury dead metaphors. If it’s boring, find another way to say it.

While Amis the critic inspired me most, something he said about his life as a novelist always stayed with me. An interviewer once asked him how it feels when a novel is going well. “It feels like talent,” he answered. That reply looks arrogant on the page, and Amis certainly had an ego. But in this instance he made clear that it was a fleeting sensation, the drug that every writer chases and can only rarely catch. I’m sure I had that experience far less often than Amis did when I turned my own hand to fiction, but every now and then it has visited me, too. Once more, Amis’s endless articulacy had captured in a few words a feeling that could fill bookshelves. I had harbored a secret ambition to send him a copy of my novel when it is published later this year, perhaps along with a tennis ball. I’m sorry I won’t get the chance to.

On second thought, it may be for the best. He might have reviewed it.

The post Criticism, Anyone?: An Ode to Martin Amis appeared first on The Millions.