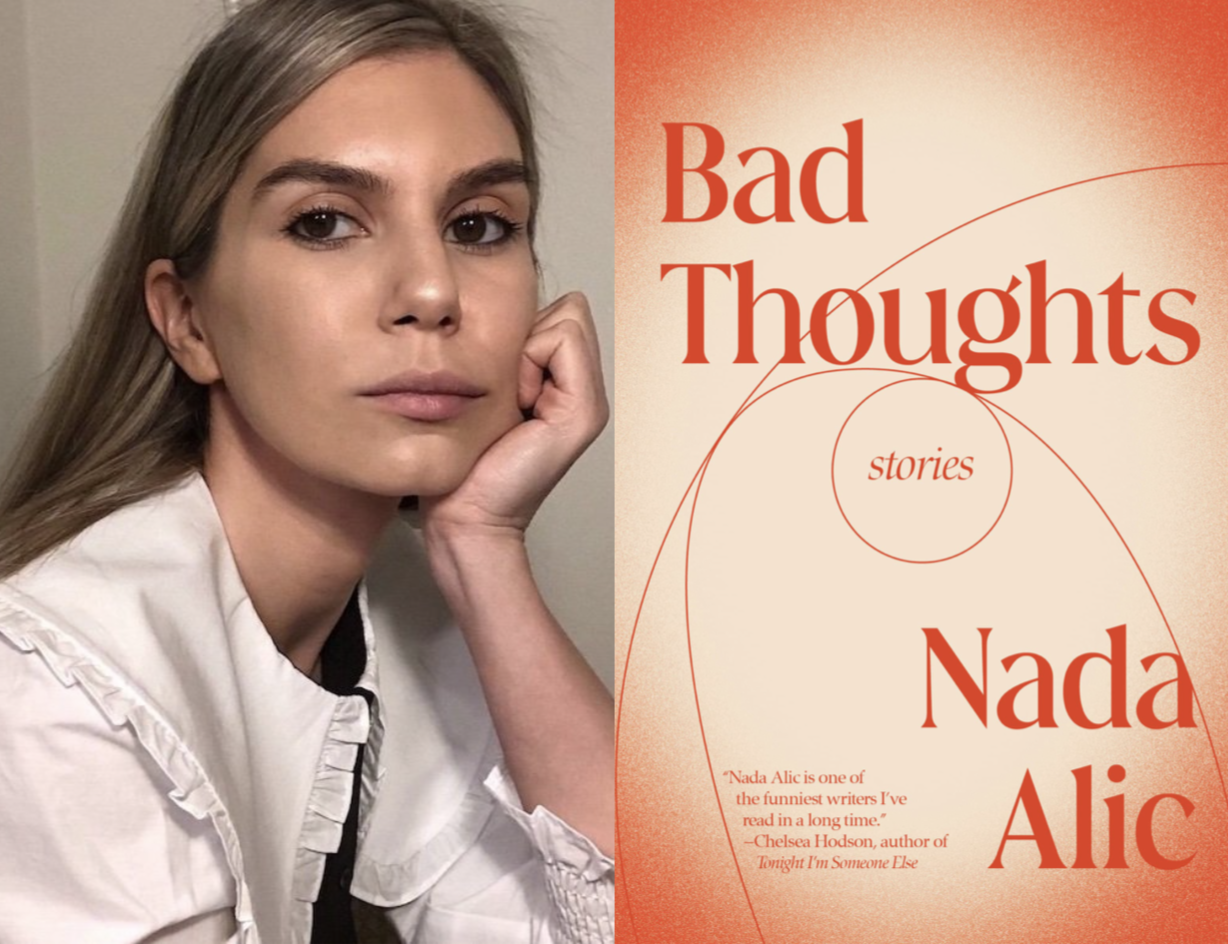

“Almost anyone can summon a spirit, but almost no one can summon the right spirit at the right time.” This is one of hundreds of achingly funny and profound truths in Nada Alic’s Bad Thoughts, the debut story collection well on its way to becoming a cult favorite among the lucidly spiritual and painfully online. I had the pleasure of talking with Nada about the thoughts behind Bad Thoughts, super sattva syndrome, the magic of mundanity, how to optimize purgatory, and much more.

Mila Jaroniec: Norman Mailer calls writing “the spooky art,” because it allows for soul communion in a way no other art does. You can talk to people, get inside them, without ever seeing them or talking to them personally. You and I haven’t met in person and only emailed briefly, yet after reading this collection, I feel like we’d be good friends in real life. Do you ever feel that way about books, almost like you lose the ability to engage with them critically because it feels like they pulled something out of you that you weren’t able to—or perhaps didn’t want to—express yourself? Which ones made you feel the most connected?

Nada Alic: I love that. What else are we doing this for? The loneliest thing about being alive is that we can only experience reality through our own subjectivity. You’re stuck inside yourself, with yourself, your past, your projections, your fears and desires. The whole point of art is to ask, Are you seeing what I’m seeing? That’s why it can feel like such relief when it clicks. It’s also why you can feel so turned off, or bored, or even angry when it doesn’t. I do think certain books come into your life at the right time, as in they find you. I remember feeling that way with Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? I wasn’t reading a lot of contemporary fiction at that point, I was reading classics or old self-help books I found at thrift stores. It felt like the book was speaking directly to me—at the time, I thought I was the only one who knew about it. I was living in Toronto and feeling so isolated, and here was this book by a woman in Toronto who, like me, also had a best friend who was a painter. There was so much vulnerability and humor in it, it’s the kind of writing that invites you in, whereas many of the books I’d been reading felt unnecessarily complicated, as if the point was to alienate and intimidate the reader, which to me read as a sign of laziness or insecurity. After that, a whole world of contemporary female authors opened up to me: Sarah Manguso, Jenny Offill, Maggie Nelson, Ottessa Moshfegh, Patricia Lockwood, etcetera. I knew I wanted to contribute to that canon in my own way.

Nada Alic: I love that. What else are we doing this for? The loneliest thing about being alive is that we can only experience reality through our own subjectivity. You’re stuck inside yourself, with yourself, your past, your projections, your fears and desires. The whole point of art is to ask, Are you seeing what I’m seeing? That’s why it can feel like such relief when it clicks. It’s also why you can feel so turned off, or bored, or even angry when it doesn’t. I do think certain books come into your life at the right time, as in they find you. I remember feeling that way with Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be? I wasn’t reading a lot of contemporary fiction at that point, I was reading classics or old self-help books I found at thrift stores. It felt like the book was speaking directly to me—at the time, I thought I was the only one who knew about it. I was living in Toronto and feeling so isolated, and here was this book by a woman in Toronto who, like me, also had a best friend who was a painter. There was so much vulnerability and humor in it, it’s the kind of writing that invites you in, whereas many of the books I’d been reading felt unnecessarily complicated, as if the point was to alienate and intimidate the reader, which to me read as a sign of laziness or insecurity. After that, a whole world of contemporary female authors opened up to me: Sarah Manguso, Jenny Offill, Maggie Nelson, Ottessa Moshfegh, Patricia Lockwood, etcetera. I knew I wanted to contribute to that canon in my own way.

MJ: Bad Thoughts deals in synchronicities, parallels. Signs you can’t ignore and doors you can’t not walk through. Equals and opposites that are really two sides of the same thing. The stories don’t end where they end; rather, they leave a talisman for the reader to pick up and walk away with, to start seeing the world through the stories’ lens, grey matter rearranged. I always appreciate that, when a writer lets the reader participate in the story. But when stories are written on paper, they end on paper. Did you ever feel quite done with these? How did finishing this collection change you, as a writer, as an artist?

NA: I’m more interested in voice and character than the unfolding of events over time. Plot is more of a loose scaffolding for characters, so if you’ve got a compelling character, they can hold your attention regardless of whether they’re going to the grocery store or doing something glamorous or exciting (see how little I care? I can’t even conjure a decent example). And so much of life is going to the grocery store. But as humans, we find grocery-store life to be so intolerable or insufficient that we create these fantasies or high-stakes dramas in our minds over nothing. I wanted to capture the ways people cope given their (often banal) life circumstances, especially dramatic or wounded people. The short story format lends itself well to this type of character study, and the restriction only helped to contain the potency. Finishing stories wasn’t the hard part, but finishing the collection was weirdly excruciating. That had more to do with my emotional resistance to allowing it to materialize into an actual book.

There are so few commonly shared events in life that mark the end of one chapter and the beginning of another. You’ve got the bookends, birth and death, then puberty, marriage, parenthood, illness, grief. The rest of your life, you forget that time is this thing you exist inside of and you’re just a frog refreshing your Gmail, slowly boiling to death. Especially in L.A., which is seasonless and no one’s face or body ever ages. I’d created this book-thing that was just an idea in my mind but now suddenly involved worldly things like a publisher and a contract and deadlines. I could have probably edited it forever, but at some point I had to be done and release it, and with it, my image of a perfect version of it. It was so painful, lonely and embarrassing. But once it was released, I felt this enormous pressure release from my body, like a really good massage, or when someone you don’t want to hang out with cancels plans with you.

MJ: Ayurvedic experts jokingly warn against super sattva syndrome, the pitfall of too much cleansing and meditation, the condition of getting and staying too pure for this world. Indeed, your characters in the story “Earth to Lydia” are in recovery from ego death. Do you think there is a risk of poisoning inherent in healing, or whatever our current concept of healing is? How do you know when you’ve gone too far away from your twisted roots?

NA: Wow, how have I never heard of that? I think about this a lot. Not that I’m at risk of ever being too enlightened—more that the ego is so insidious that it can masquerade as enlightenment and fool us into thinking we’ve reached a state of permanent wholeness because we maybe briefly encountered it or have read a lot about it. The entire wellness and spirituality industry is based on this false premise that there is somewhere to arrive to, and by working on yourself, taking classes, and following special protocols you can get there. A lot of our pursuit of enlightenment is a rejection of our human form for something that is out there and beyond us. It’s preoccupied with the spirit realms, dreams, heaven, even space. That’s why I love Buddhism so much—because it’s spacious enough to include both form and spirit, with an understanding that they are inseparable.

Having a spiritual practice can be a useful tool for engaging with the mystery of reality, but it needs to be uncoupled from the idea that a perfect version of us exists just out of reach, and if we could meditate enough, pray enough, be “good” enough, we can escape our suffering and finally be at peace. In Christopher Lasch’s 1979 book The Culture of Narcissism, he talks about this obsession with self-help, wellness, and spirituality as a symptom of a civilization in decline. When day-to-day life becomes untenable, people turn inward and focus on what they can control, like improving their bodies and minds, or seeking salvation from spirituality, i.e. having a “personal relationship with God.” The absence of community or any real hope for the future makes narcissism a survival mechanism. Knowing this, I’m still clinically addicted to self-improvement and spirituality, because I’m not above accepting my lot as a product of my environment.

Having a spiritual practice can be a useful tool for engaging with the mystery of reality, but it needs to be uncoupled from the idea that a perfect version of us exists just out of reach, and if we could meditate enough, pray enough, be “good” enough, we can escape our suffering and finally be at peace. In Christopher Lasch’s 1979 book The Culture of Narcissism, he talks about this obsession with self-help, wellness, and spirituality as a symptom of a civilization in decline. When day-to-day life becomes untenable, people turn inward and focus on what they can control, like improving their bodies and minds, or seeking salvation from spirituality, i.e. having a “personal relationship with God.” The absence of community or any real hope for the future makes narcissism a survival mechanism. Knowing this, I’m still clinically addicted to self-improvement and spirituality, because I’m not above accepting my lot as a product of my environment.

MJ: At one point in the story “The Intruder,” the narrator zones out while having breakfast with a friend. “As he talked, I softened my gaze and visualized myself back in my room,” she says. “I’m surprised more people don’t do this—you can think about whatever you want and watch it in your mind like a movie.” Sometimes it feels surprising that, instead of forcibly filling your time, you can just think. But a lot of people have a hard time inhabiting themselves—their brains are inhospitable environments—so they distract themselves ad infinitum. When you feel distant from or at odds with yourself, what helps you find your way back? How rooted in yourself do you need to be to write at your best?

NA: My brain can be very inhospitable, too. I used to think there was something uniquely wrong with me until I read those mandatory artist-books like The Artist’s Way, The War of Art, and The Untethered Soul. When I learned that the brain’s job is not to be happy, but to constantly scan for threats—even when there are none—and that painful early childhood experiences put this nonstop threat-scanning into overdrive, I started believing my thoughts less. They sound so convincing though, right? I’m sure one day they will invent a way to differentiate the sound of that primal, paranoid voice from your true self, but until then, you just have to stay vigilant. I was listening to Duncan Trussell’s podcast the other day and he was talking to one of his spiritual teachers, and the teacher was like, “You must listen for the still, small voice within,” and Duncan said, “Why’s it gotta be so still and small?!” It made me laugh! I always think about that. If your higher self is really trying to send you a message, why not make it a little louder than that annoying default ticker tape of thoughts? I actually have no advice for how to get around it besides the very boring: sleep, exercise, write in the mornings, be kind to yourself, etcetera. Half the time I neglect all of the above, but I still somehow managed to painfully, tediously, over many years, write a book. Anything is possible.

NA: My brain can be very inhospitable, too. I used to think there was something uniquely wrong with me until I read those mandatory artist-books like The Artist’s Way, The War of Art, and The Untethered Soul. When I learned that the brain’s job is not to be happy, but to constantly scan for threats—even when there are none—and that painful early childhood experiences put this nonstop threat-scanning into overdrive, I started believing my thoughts less. They sound so convincing though, right? I’m sure one day they will invent a way to differentiate the sound of that primal, paranoid voice from your true self, but until then, you just have to stay vigilant. I was listening to Duncan Trussell’s podcast the other day and he was talking to one of his spiritual teachers, and the teacher was like, “You must listen for the still, small voice within,” and Duncan said, “Why’s it gotta be so still and small?!” It made me laugh! I always think about that. If your higher self is really trying to send you a message, why not make it a little louder than that annoying default ticker tape of thoughts? I actually have no advice for how to get around it besides the very boring: sleep, exercise, write in the mornings, be kind to yourself, etcetera. Half the time I neglect all of the above, but I still somehow managed to painfully, tediously, over many years, write a book. Anything is possible.

MJ: Do you have a literary predecessor? Is there a writer or artist whose torch you feel you’ve inherited?

NA: I don’t know how much I’ve inherited from any one writer or artist. I think it’s more about that recognition we were talking about earlier, that feeling that you’re communing with someone in a place that transcends space-time. Beyond writing, I look to other artists to see how they built their careers, their bodies of work and how they’ve sustained their creative practices. So in that sense, I’m inspired by artists like Marina Abramović, Agnès Varda, Marguerite Duras, Nora Ephron, Hilma af Klint, Anaïs Nin, Daša Drndić, etc. But the artist who has inspired me the most, even just through 14 years of osmosis, long phone conversations, collaborative art projects and daily texts would be my best friend Andrea Nakhla, a painter who has introduced me to so much art, poetry, philosophy, so many new books and ideas. She’s an endless wellspring for me and also a mirror to better understand myself. She was the first person who believed in me as an artist and encouraged me to keep going. Imagine having all that in one friend! Clearly, God loves me.

MJ: The stories in Bad Thoughts are separated by lists of bad thoughts, including hilarious and uncomfortable truths like “‘Thoughts aren’t real, let them pass like clouds in the sky,’ but also ‘Thoughts manifest your reality and steer the course of your fate,’ okay, good luck!” I looked forward to them every time. Can you share some more thoughts that didn’t make it into the final draft?

NA: “Only the most powerful person gets to claim the corner of the L-shaped couch”

“God blessed me with very few followers because he wants me to work on my art instead”

“Addicted to saying ‘noice’ around my guy friends”

“My secret talent is that when I pee in my dreams I don’t pee in real life”

“I can’t stop Shark Tanking my richest friends”

“Love to tell a man that I don’t know about a band just to watch them have a full meltdown”

“The violent betrayal of discovering that a dress is secretly a romper”

MJ: Do you have any advice? Not for writing or publishing necessarily, just in general.

NA: So much of writing and being a full-time artist requires a level of waiting that feels inhumane. There is so much waiting involved. It always takes so much longer than you think it will and during that time, you find yourself waiting for anything to happen. For me it was waiting to hear about a pitch or a residency or a grant application, or waiting to get an email from my agent, or waiting for my book to sell, then waiting a year before it came out, then waiting for people to review it. Even looking at social media is waiting. You’re waiting for stimuli to respond to. Now, if I find myself caught up in waiting, I have to do something. I have to act. Instead of waiting for the world to impose itself on me, I will impose myself on the world. I will start a new project or revisit an old one. I will text a friend I haven’t talked to in months. I will plan a reading or a dinner party or something to look forward to. Sometimes I forget I’m still allowed to participate in life while I wait for my “real life” to begin. Because that is at the core of all waiting: the false idea that the future is real, and the present is just emails and errand time. Doing instead of waiting gives me a sense of agency and puts things into motion. Whenever you get the urge to wait, or feel that restless sense of How come nothing’s happening yet? ask yourself, What am I doing to make something happen?

MJ: And finally, three words to describe your upcoming novel?

NA: Nathan for You-ish.

![‘The Amazing Race’ Season 34 Premiere Recap: [Spoiler] Eliminated ‘The Amazing Race’ Season 34 Premiere Recap: [Spoiler] Eliminated](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/amazing-race-season-34-derek-claire.jpg?w=620)