Caroline Hagood and I hop on Zoom because we cannot find time to meet in person. My son started Pre-K and immediately got sick, so we’ve been hanging out and watching Lily Hevesh make domino structures for the past three hours. Caroline has just gotten back from teaching a full class schedule, and she’s on the “second shift,” parenting two energetic kids.

Sometimes it feels like there is no room for art in our lives. For this interview, I’m sequestered in the bedroom while my husband keeps our son from barging in and our baby from banging her head on the table. Caroline’s kids keep barging in too, adorably, to see what their mom is doing. This is what it means to be a mother and a writer—finding the time to talk about art in a chaotic environment.

I met Caroline in grad school, in awe of the fact that she had a book of poetry published and a famous person had talked about it. Damn, I thought, she’s really got it together. As we became friends and cried together about our never-ending dissertation dramas, I was delighted to discover that Caroline was just really weird in a true, deep way—not a manic pixie dream girl way—and that we had a ton in common.

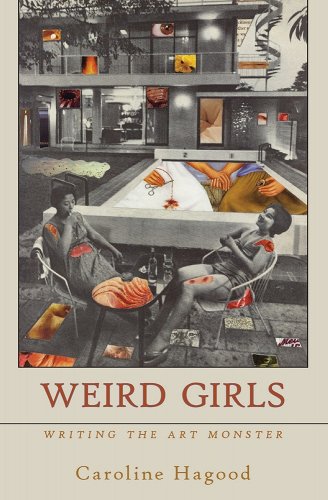

When I read her latest book, Weird Girls: Writing the Art Monster, I was excited to see her grapple with the imposed borders between the experience of motherhood and the practice of being a writer. Any mom who writes knows what it’s like to steal moments for creativity—and to feel guilty about it.

Patricia Grisafi: I love seeing people’s writing spaces. Can you tell me about yours?

Caroline Hagwood: I do have a designated space, but what’s funny is that it’s an all purpose room. Somebody was putting out a broken down desk, like an old and ugly one. They put it out on the street on front of our house. I pushed that against the wall in here. My kids are still too afraid to sleep in their rooms, so we have mattresses on the ground. So this is the room where both my kids sleep, the only room that all the books fit in, and this is the room where I do all my work and writing.

PG: The room where motherhood and writing merge! Did you write Weird Girls like this?

CH: It’s the only place I could write! At work, I used to have a “room of one’s own” that was the only place in my life I had my own space. I would stay there until 7pm on Friday. But now they’ve restructured the department, and I lost that space. My kids play in this room, and I could keep an eye on them while I was working. My son is interested in writing, and he asked me tons of questions while I wrote Weird Girls.

PG: You made the best of it.

CH: I am a glass-half-full person because my glass has been half empty so much. It’s the only way I can function. I mean, did we not live through a dystopia and see that we were the heroines of our own stories?

PG: We’re still living in a dystopia!

CH: True!

PG: It feels so long ago, but when I first met you in grad school, you had a book of poetry out. Now, you’ve written Weird Girls, which is a mixed genre book, and are at work on another project. How was your writing evolved and why do you think you’ve gravitated to this hybrid form you’ve been working in?

CH: My brain will always think in poetry. But I read everything and I read a lot. My favorite books are like Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. Like the stuff coming out of Graywolf. My favorite genre of all is the lyric essay. Once your body is blown open [in childbirth], you see things differently.

CH: My brain will always think in poetry. But I read everything and I read a lot. My favorite books are like Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. Like the stuff coming out of Graywolf. My favorite genre of all is the lyric essay. Once your body is blown open [in childbirth], you see things differently.

PG: It’s been this way in horror films, talking about motherhood in this primal, bloody, and violent way. You touch on that in your book.

CH: Horror movies are always ahead of the curve. And stand-up comedy. If you want to see any aesthetic trend emerge, go see horror movies, go to comedy shows. In grad school school, the same professor who taught composition and pedagogy also taught the horror film class, Moshe Gold. We would talk about the aesthetics of writing and then monsters. It just fit so well together.

PG: I took the monster course, too! One of my favorite classes and teachers ever.

CH: They [monsters and writing] really merged in my mind. I think of creativity and writing being so much about monsters. Moshe was fantastic. He had a huge impact on me.

PG: How did becoming a mom affect your approach to writing and genre?

CH: There’s this idea that there’s a fragmented kind of writing associated with motherhood. You’re always getting interrupted. You write on grocery lists, on the way to birthday parties. By the way, there are lots of cool dads who probably understand me more than some moms. I think stay-at-home dads are so sexy.

PG: What is hybridization but interrogating boundaries and destroying them? Like, you write a lot about the boundaries between motherhood and teaching and writing.

CH: I showed up to class one day in a fancy black shirt, and there was some kind of child-related goop on my back. I had to stop trying to control how I appeared to people.

PG: When you have a kid, you’re always apologizing. How does the art monster liberate you?

CH: The art monster is the sense of creativity and getting rid of all the notions of being a woman. These feelings have been inside, that whole sense of people pleasing and caring for everyone… I felt like if I didn’t give my art monster life, I was going to disappear. I was going to lose my mind. I fight for my writing. I will be so tired and drink espresso at midnight because I need to get writing done. I will run myself into the ground.

PG: Monsters are not always about badness.

CH: They’re about hybridity.

PG: I mean, you named your son after the kid from Where the Wild Things Are! I love that. Kids love monsters. My son is obsessed with Bigfoot.

PG: I mean, you named your son after the kid from Where the Wild Things Are! I love that. Kids love monsters. My son is obsessed with Bigfoot.

CH: Even though I’m teaching my kids how to be in the world, I want them to hold onto their wildness. I’m trying to find this space, especially with my daughter. How can she stay wild while navigating a world not made for her? I can say to my husband, please take my kids to the playground because I am writing, and that matters! And that is what can feel monstrous—it can feel monstrous to just say, Can you make dinner tonight, I’m writing.

PG: Speaking of dinner, if you could share a meal with three writers, who would they be?

CH: One of them would be Claudia Rankine, then Virginia Woolf, and Audre Lorde. Virginia Woolf is on my wall, she means a lot to me. Her diaries and all of her books. She’s such an art monster. And Audre Lorde, her poetry and essays—she moves between genres and her activism and vision of a more inclusive and creative world. I love the way she shows things to me in new ways.