When my mother and I used to ride the New York City subway together, she would look at the men sitting across from us with their legs splayed and launch into a rant about the entitlement that allowed them to take up so much space. Couldn’t they squeeze their knees together as we women did to create room for another person to sit? She had resented male privilege all her life; I suspect she even resented my son as a baby, before he became a person she loved.

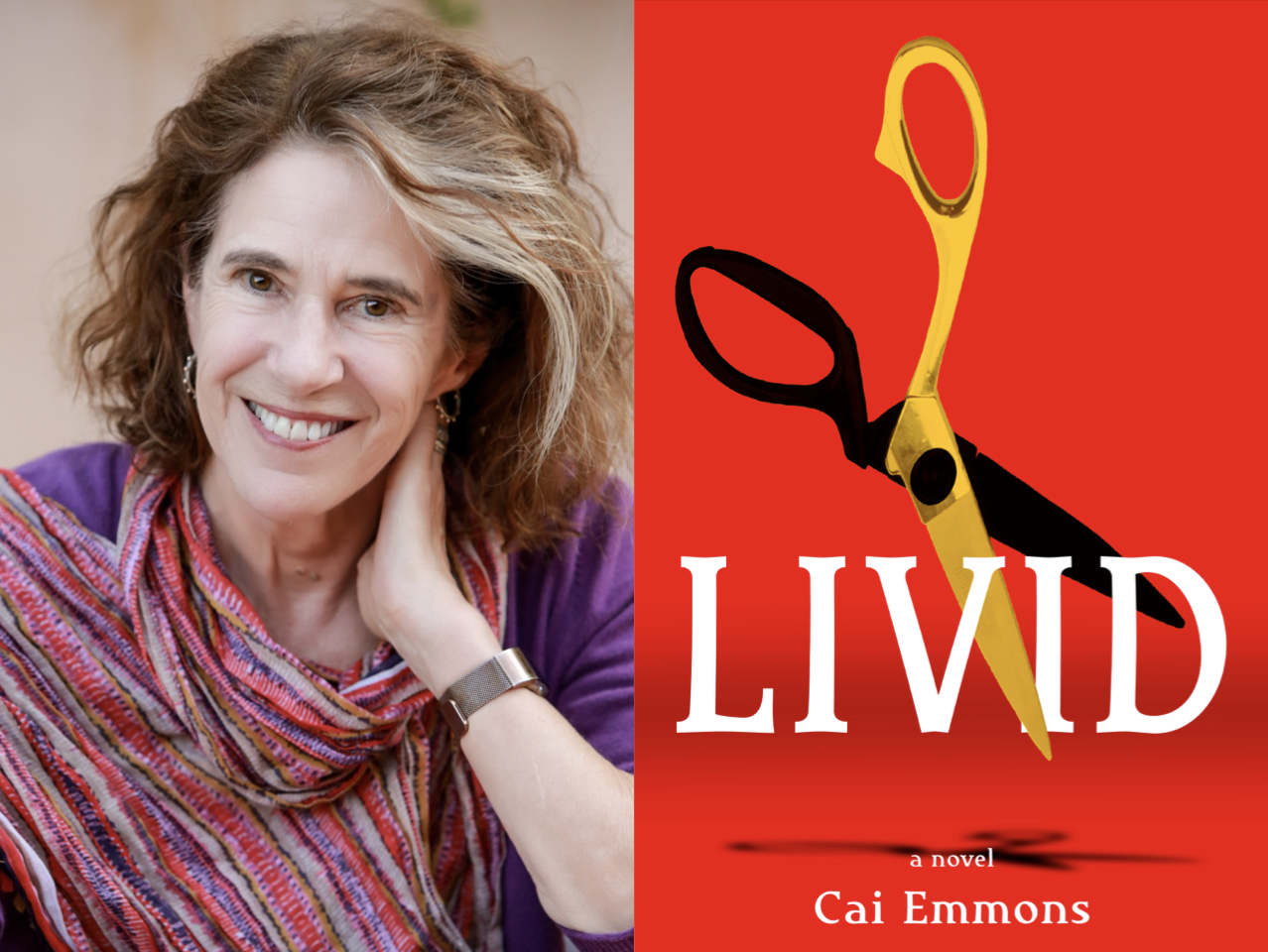

I’ve summoned these memories because of the imminent publication of my new novel Livid, which explores female anger—in particular the kind of low-key anger my mother harbored, which was always simmering under the surface of a friendly, extroverted, life-loving woman. Sybil, the protagonist of Livid, is assigned to sit on a jury with her ex-husband to decide the fate of a woman who is accused of killing her own husband. Sitting in the courtroom day after day, Sybil has plenty of time to ruminate about her rage, the defendant’s rage, and how this binds them as women.

Though on the surface I am cheerful as my mother was, I have been riding a rollercoaster of anger all my life, beginning as a teenager when I attended a predominantly male college and watched every weekend as women were imported as sex toys for my schoolmates. Outrage propelled me to work for an abortion referral service pre-Roe,where we helped desperate women of all ages, from all over the country, get abortions in states where they were legal. And in my thirties, I felt indignation as a filmmaker when cinching a job at the helm of feature film was, for women, like threading a camel through the needle’s eye. Finally, rage dogged me into the worlds of academia and publishing where in both arenas lip service is paid to gender parity, but nevertheless men receive higher pay, hold most of the top jobs, get more regular promotions, and receive more recognition in the form of publications and prizes.

My mission is to explore what it means for women to live on such a rollercoaster of anger. My mother and I are not alone. Most women I know have been angry in similar ways, suppressing the feeling for stretches of time until it explodes again with the right catalyst—when we lose out on a job to a less-qualified male candidate, when our husband neglects his share of childcare duties; when we are accosted on the street or groped on the train; when a sniveling liar is appointed to the Supreme Court. We may explode for a while, then we usually suck it up and move on into another day, another week, month, year, seeing the same patterns repeat but wondering if we have the requisite energy to make a fuss. These periods of silence take a toll: we might turn our unexpressed rage inward, where it congeals into depression, health problems, addiction. Anger moves in our bodies in mysterious ways, and attempts to address it can feel like playing whack-a-mole; we are constantly punching it down only to see it rise again.

Of course, none of this is new; women have resisted male predominance for centuries. In the U.S. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote A Vindication on the Rights of Women in 1791, and well before that, in fourteenth-century France, Christine de Pisan wrote The Book of the City of Ladies. Earlier still was the barricading of the Roman Forum when women were protesting a law that forbade them from using expensive goods. And, one can’t forget the Aristophanes play Lysistrata, written around 411 BCE, in which women protested men waging war by refusing to have sex.

Of course, none of this is new; women have resisted male predominance for centuries. In the U.S. Mary Wollstonecraft wrote A Vindication on the Rights of Women in 1791, and well before that, in fourteenth-century France, Christine de Pisan wrote The Book of the City of Ladies. Earlier still was the barricading of the Roman Forum when women were protesting a law that forbade them from using expensive goods. And, one can’t forget the Aristophanes play Lysistrata, written around 411 BCE, in which women protested men waging war by refusing to have sex.

So what can be done with our anger now? Experts tell us to meditate, breathe deeply, or exercise as ways to manage our rage. When I was a kid, my mother bought me a weighted blow-up Bobo, a clown that I was supposed to punch during my temper tantrums. But Bobo only infuriated me more by popping back up. Such solutions might calm us or distract us from our anger, but they don’t address the source. Is there some way to really alter things so we aren’t doomed to push the proverbial rock up the hill again and again?

From this vantage point, I see a future in which women will have to continue to assert our equality and rights over and over again. Seeing Roe appear and disappear during my lifetime has shown me that. Rights have a tendency to disappear right at the moment we assume they are permanent. We need to keep our anger alive. To speak up, engage in conversations, write, protest. To give voice to anger, without apology. Most of all I think we need to learn to not to be afraid of our anger but to harness it as a force that binds us.