“Tell me, my daughters,” says King Lear, announcing his intention to divest himself “of rule… [and] territory,” of “cares of state,” as he points to a map of his kingdom spread out before him. “Which of you shall we say doth love us most / That we our largest bounty may extend?”

In attempting to take love’s measure, to size it up and apportion its material reward, Lear touches off the tragic series of events that will eventually destroy his house and all who inhabit it. Tragedy is, by definition, a face-off between incommensurable spheres; it draws us round to witness the collision of two competing, equally worthy, yet mutually exclusive claims.

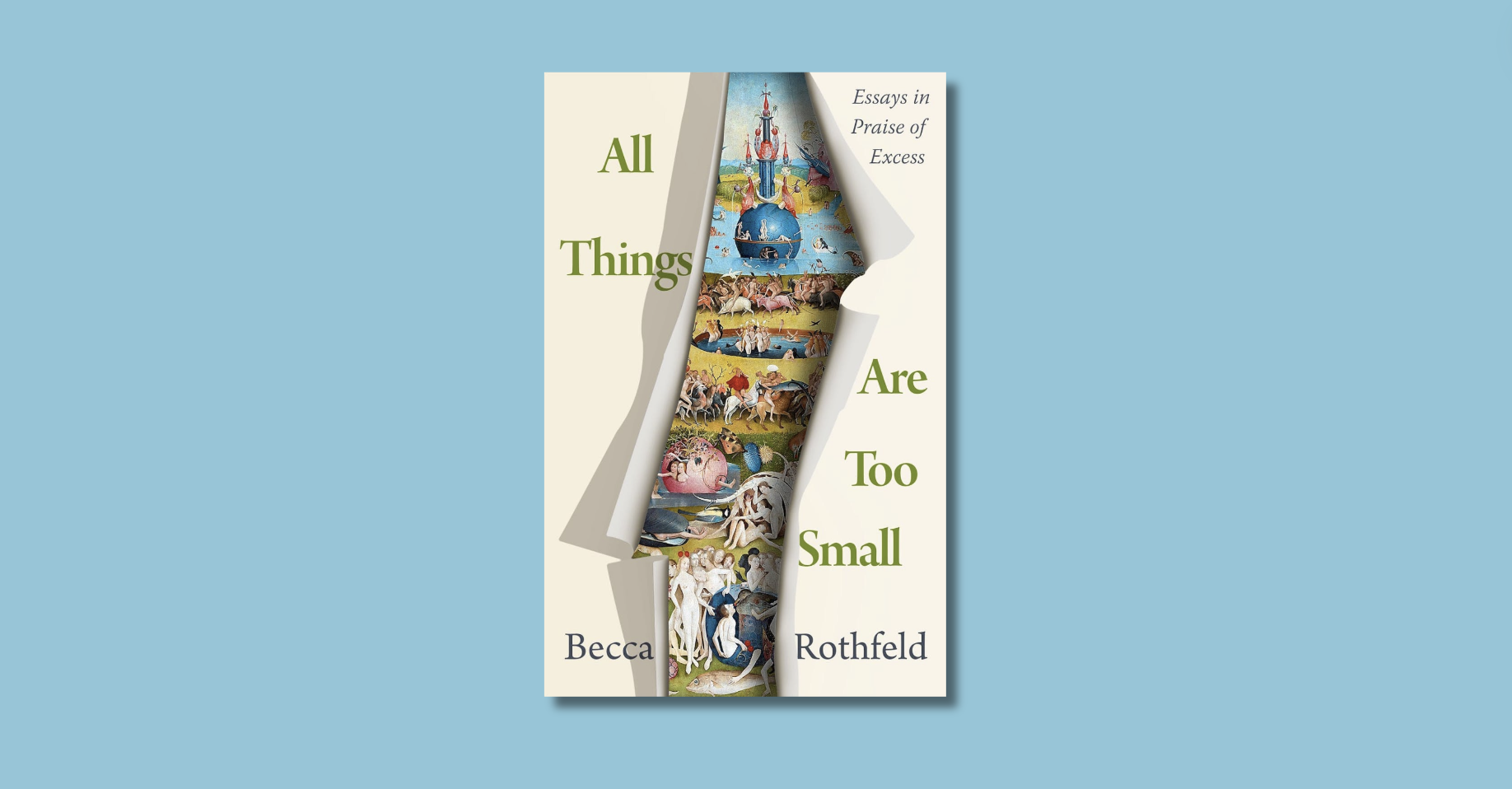

Becca Rothfeld’s new book, All Things Are Too Small: Essays in Praise of Excess, is not overly given to the tragic mode. On the contrary, her prose is robustly Rabelaisian, warm and mirth filled. Her beautifully crafted sentences are a testament to language’s sensuous abundance. Nonetheless, the book’s chapters might also be read as a series of exceptionally perceptive glosses on the tragic and tragicomic effects that ensue when contemporary culture strives to carry the rules of justice proper to the political and economic realms over into the decidedly less regular and regulatable spheres of love, sex, and art.

Rothfeld, a philosopher by training, prefaces the book by citing political theorist John Rawls’s proposition that a just state must follow the rule of equity in dividing up political and economic power amongst its citizens. But when the drive for equality creeps outside the public square into the private corners of eros and art, Rothfeld warns, it overreaches its proper jurisdiction. Our longing for the beautiful, like our longing for the beloved, is characterized by what Emily Dickinson might have called “a wilderness of size”; it is righteously allergic to any attempt at apportionment. The impulse to square love and law is, as Lear learns to his sorrow, always a fool’s errand.

An encomium to excess, All Things Are Too Small devotes several of its 12 elegant essays to skewering the pervasive modern infatuation with “downsizing.” It is a word whose prim air of moral self-satisfaction, of fat-trimming and fiscal responsibility, may be fitting enough in the economic sphere, she argues, but has no business regulating our interior spaces, our spiritual lives, or our art. From Marie Kondo to the contemporary mindfulness movement with its origins in nineteenth-century American New Thought, Rothfeld traces the popularity of the less-is-more mantra as it migrates from decluttering our physical living spaces to depopulating our souls and psyches.

The declutterer prioritizes a pared down life that would theoretically permit her to pull up stakes at a moment’s notice: she is perpetually poised to start over, turn the page, wipe the slate clean. The key is to “keep the vacuum from filling,” Rothfeld observes, “to keep time from concatenating into chronology,” maintaining instead the “gleaming purity of ahistoricity.” Similarly, mindfulness advocates attempt to whittle consciousness down to an evenly distributed field of neutral awareness, stifling all preference as signs of an unhealthy “attachment.” Rothfeld has particularly sharp words for this impulse as expressed in the past decade’s fad for “fragment novels”—she has Jenny Offill, Kate Zambreno, and Sheila Heti in her sights—that swap out the cluttered fulsomeness long associated with the form for “the thin warbling voice of a placeless, hungerless narrator.” The shrugging off of worldly attachments by these novels’ protagonists is matched on the formal level by novelists “who have dispensed with [all] contrivances of plot,” as if such plodding commitment to historical cause and effect were morally suspect (25).

The spiritual declutterer, like the minimalist novelist, seeks—on the face of it—to evade the alienation intrinsic to a world where mass consumption and modern market society have rendered all values suspect. But to react to dismal social and economic and political conditions by reducing the self to Bartleby-esque paralysis is, at best, to settle for false consolation; at worst, Rothfeld suggests, it is to stand idly by as neoliberalism co-opts the cultivation of “detachment” to give itself a patina of virtue. What imagines itself as an antidote to the glut of consumer capitalism ironically ends up mimicking the market’s own zeal for a frictionless evacuation of content. Deprived of an outside to butt up against—the stubborn facts of history, say, or other people who might reasonably resist our attempts to detach from them and our intertwined histories—we are left only with the echo chamber of a brittle, control-obsessed “self.”

What is required in the aesthetic or the amorous or the expansively spiritual mode, then, is not “control,” but rather what Rothfeld calls “capitulation”: a willingness “to crash into something that is not in its proper place and that is therefore equipped to trip and torque us.” And this is precisely where Rothfeld’s thinking gets most interesting. If we want to be true to the experience of desire—whether for the beauty of art or the beauty of the beloved—we must be able to imagine, and tolerate, an entirely different form of selfhood: one that is open to the risks of rapture.

“Beautiful things do violence to us, their viewers, by assaulting our strident sense of centrality,” Rothfeld argues in her superb essay on aesthetic absorption, “On Having a Cake and Eating It Too.” “A glimpse of beauty heightens our vulnerability and thins us, […] skimming the self so that the world streams in to fill the space we vacate.” From Plato’s Phaedrus to Dante’s Beatrice, beauty stops the viewer in her tracks, renders her powerless, and thereby “inverts the usual sites of passivity and activity.” The encounter with the beautiful paralyzes us with a mortifying blend of elation and impotence. “We want to act on beauty, but we don’t know how,” Rothfeld observes of this painful condition. The impulse to put one’s arms around the beautiful thing gets us no closer to its mystery. “For the most part,” she glosses, “it’s not even interactive. You just have to endure it.” “Violence,” “assault,” “passivity,” “vulnerability,” “endurance”: the experience of self in a state of aesthetic absorption is at the furthest remove from the selfhood required of us in our capacity as political, legal, and economic actors.

What is true of the desire that binds us to the beautiful in art and nature is equally true of erotic desire. In “The Flesh, It Makes You Crazy,” Rothfeld braids together confessions of her own experience of overwhelming physical desire with sharp analyses of David Cronenberg’s darkly lustful, frequently abject films. The ravenous zombies and human-fly hybrids that populate Cronenberg’s films are simply hyperbolic expressions of the power eros holds to unmake and remake our very sense of who we are as flesh-and-blood bodies, often in ways we cannot predict and that risk undoing our most cherished beliefs about ourselves.

The unforeseeable quality of erotic experience leads Rothfeld to a much longer meditation, “Only Mercy,” in which she examines consent in the era of #metoo. Here, Rothfeld patiently probes the limits of sex defined by contractual safety and rule-abiding regularity, examining how “post-consent feminists” end up mirroring conservative sex “puritans” in making of sex a means to a utilitarian end; whether that end is social justice or procreation matters little, she suggests. In both essays, Rothfeld commits to the idea that erotic experience sometimes involves breaking the self in ways that one cannot predict will “turn out ok.” “We lack access to information that we can acquire only by plunging into the scalding water of a new life,” she explains, “but we cannot foresee how such a jolt will overhaul the very predilections and values that define us as the people we are at the moment.”

In line with a heterodox school of philosophers that includes Simone Weil, Emmanuel Levinas, and Iris Murdoch, Rothfeld’s essays make a sustained argument for aesthetic and erotic experience as spheres of human activity where we are most likely to come into ethical contact with the other: that is, contact that forces us to acknowledge the absolute and sacred separateness of something that exists outside our own own ego. Sex is “a moral matter” for Rothfeld precisely insofar as it “challenges us to make real—and therefore unexpected and disorienting—contact with other people, rather than glancing contact with the affirming balm of our own fantasies.” In aesthetic and erotic encounters alike, we are given an opportunity to let the sheer strangeness of the other “challenge and change what we want.” The magnetic pull we feel in the presence of beauty, in the presence of the beloved, invites us to make ourselves anew, create ourselves from scratch, “starting now”—and this radical experience of originality cannot be stuffed into the narrow ledger of prescriptive rules and rights. “Longing reinvents us, […] but it does so by tyrannizing us,” Rothfeld explains. Our ethical duty reveals itself most clearly when we come face-to-face with the other’s stubborn reality, their “tyrannical” inaccessibility to all our attempts to control or possess them. In short: for Rothfeld, there is no experience of longing that is not, at the same time, an ethical revelation.

Rothfeld’s collection is a powerful meditation on this core human predicament: that what counts as the highest value in the “public” economic, legal, and political spheres—equality and predictability—counts for nothing or next to nothing once we pass into the parallel “private” spheres of art, sex, and love. All Things Are Too Small is an exuberant, moving, and ultimately persuasive argument for giving desire, whether in love or in art, its due. That is, for taking the risk that desire might, indeed, un-do us, and that this undoing might be worth the price.