A young woman who is not that young anymore hates her sleepy little Swiss hometown but can’t bear to leave it. Her childhood house is big but empty, preserved but in a state of decay. Her parents have moved somewhere else, her siblings have their own families, the neighbors pass her with polite distance. She gets the ominous sense that everybody is waiting for her to move on too—but to what, and where?

Swiss playwright Ariane Koch’s debut novel Overstaying, translated from the German by Damion Searls, presents the woman’s next challenge right away. Just when she is contemplating boarding a train for the first time, she spots a stranger at the station—“the visitor.” Instead of going out into the world herself, she invites him to stay with her. “Besides,” she convinces herself, “he brings the whole world here to me right at home, I don’t even need to turn on the radio.” Immediately, the visitor consumes all of her attention.

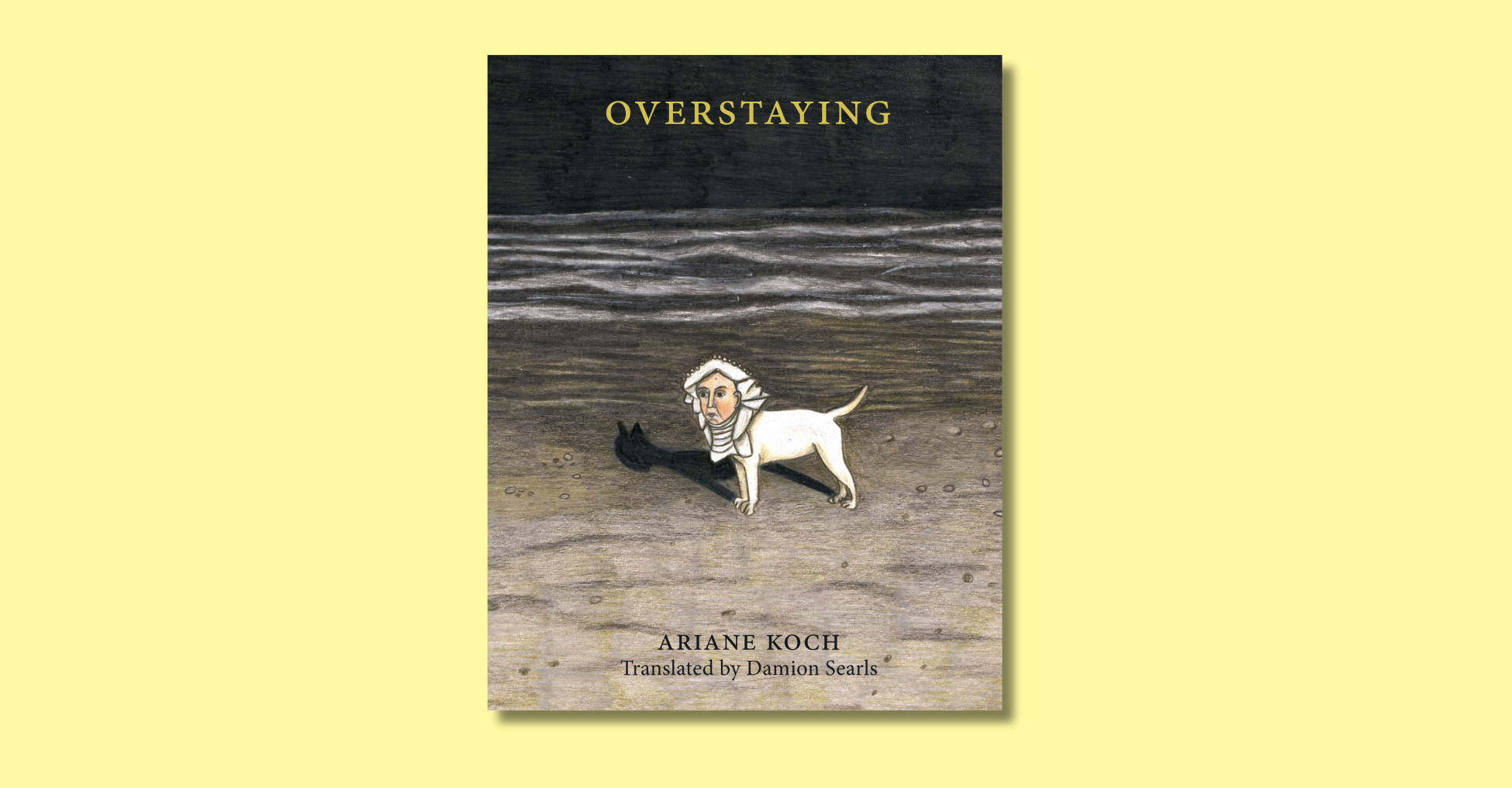

Overstaying openly invites the mystery of the nameless visitor. Who is he? “The visitor’s shape is very changeable,” the narrator ruminates, “according to the growth of his beard, the time of day, whether the milk has spoiled his while, or whether the housework he is supposed to do has been carried out.” Sometimes, he howls like a wolf, others he climbs into bed with her. Sometimes, he’s at peace, angelic; other times he’s rageful and demonic. Much like Frankenstein’s monster, he is beloved and despised, child and adult, gigantic and teeny tiny, always shape-shifting.

At first, the experience of reading Overstaying is reminiscent of a Méret Oppenheim photograph or a Barbara Comyns novel. With short chapters and peculiar language, Koch gives sentience to vacuums and walls; she makes rooms disappear “like earrings,” shrinks the local bar and its customers, turns every moon red or full or new, and breaks a mountain in half. The narrator’s fragmented monologues evoke the surrealist paintings like Leonora Carrington’s Self-Portrait and Dorothea Tanning’s Birthday, both shadowy depictions of women found wild in domesticity. By exaggerating size and proportion, Koch—with Searl’s tasteful translation—gives us this creepy, unforgettable experience of the claustrophobia that comes with overstaying.

But who, really, is the one overstaying? The visitor who spends day after day in the shrinking house into which he was invited? Or is it the woman who refuses to leave her childhood behind? While Koch seduces the reader with the obvious enigma of the visitor, she also subtly creates a playful twist on a coming-of-age story.

In careful layers, Koch’s narrator begins to tease out the tension of resisting the world of adults. Like a traditional bildungsroman, Koch gives voice to the young woman—a darkly comic, psychodramatic narrator with polarized desires, resentful aimlessness, and resistance to tedious cultural expectations. She imagines herself heroically as a warden of ruin, a tomb-keeper, the “oldest fossil of all” living in a town of other people she thinks of as fossils. Meanwhile, the visitor is her “scientific experiment,” who begins to consume all of her attention. She wants an excuse to feel as bad as she does. She wants to exaggerate everything. She needs to self-destruct, or else, she needs to grow.

Right away, the beginning of Overstaying has the immature narrator wondering why everyone, including herself, is obsessed with miniatures. Little towns, little children, little tangerine slices. One begins to wonder if she wants to remain little forever. After seeing the visitor for the first time, she “imagined the small town getting smaller and smaller, shrinking down to a tiny point—I alone remained large, so I longer fit in it.” By the first few pages, claustrophobia has already taken hold.

This landscape echoes the familiar tensions of a coming-of-age story: will our narrator ever get out of here? Can she join the adults of the world? If Holden Caulfield were a woman from a small town in Switzerland, maybe he would’ve taken in a pitiable man and given him an inhospitable bedroom with a “herd” of vacuum cleaners as revenge. Maybe this female Caulfield would resist the phonies of the world by domesticating herself in smallness instead of wandering the tremendous streets of New York City. But unlike Salinger’s narrator, Koch’s is already an adult, stuck in arrested development and fantasy, clinging to a childhood she can’t even idealize. I suspect many of us readers can relate.

Koch wants to remind us of the real tragedy of growing up in a world that rewards ignoring problems and pain: that to function as an adult requires cultivating a kind of numbness, or at least learning to manage and mask one’s sensitivities. Is achieving “maturity” just learning to be polite?

When we are first getting to know the narrator, she looks around at her far-from-idyllic town where people live in tents. She notices one woman who sleeps on the street every day. “We don’t say anything, we just share this look,” the narrator tells us. While Koch allows the ruminations to shift more toward the domestic and psychological, she keeps returning to the external world. This critique of cultural “maturity” is a painful reminder that often, learning to be an adult means accepting such situations as inevitable, rather than feeling moved to change things. “Since the visitor’s arrival,” the narrator tells us, “I’ve found that heads in general are quite heavy. Since the visitor’s arrival, I’ve wondered why we even have heads when they’re so often turned in the wrong direction.”

Coming of age, Koch seems to say, means leaving something behind. The romance of leaving only makes you more of an outsider—always the invasive visitor. As a Swiss German, perhaps it can be read one way, as an American another. Either way, there’s no way out.

With an astounding understanding of what it’s like to be stuck in arrested development in a world that seems to favor it, Koch gives us an unlikeable protagonist we can relate to. Full of self-doubt, the narrator spins several versions of the same stories, never knowing where to place the blame for her unhappiness. Finally, she begins to take on a new, more lucidly mature tone. Like Caulfield, she discovers what we all know to be true of the adult world, but Koch gives us a gift of leaving this reality as an almost funny dream: you’re on a moving train watching the world fly by, your teeth are crumbling out, everyone around you is asleep or looking down. And the second you wake up, you gratefully forget what just happened.