Good Girl—the debut novel by award-winning poet Aria Aber—follows nineteen-year-old Nila as she becomes charmed in a Berlin club and falls manically in love with Marlowe, an older brooding American writer. Raised by Afghan refugees, Nila’s childhood remains haunted by the shadows of exile while she yearns to be free and to live life outside of the realms of her room. She follows friends and strangers into dark warehouses and neon dancefloors, and soon stumbles upon an upper echelon world alongside Berlin’s underground scene, finding out that both orbit around art, sex, drugs, God, and secrets. “The club wasn’t really called the Bunker, but that’s what I will call it, because that’s how we experienced it: a shelter from the war of our daily lives, a building in which the history of this city, this country, was being corroded under our feet, where the machines of our bodies could roam free and dream.”

Aber’s novel might be considered a künstlerroman and a bildungsroman. The portrait of the young photographer. A story about an artist becoming herself. But what happens when that self is obscured in lies, grief, and shame? What if the identity she is becoming is only an image of someone else entirely, then what might one be left with in adulthood? Above all, Good Girl proves itself to be much more layered than a genre-defined künstlerroman or bildungsroman. It is a complex, multidimensional story—not only a coming-of-age but a poetic journey that traces a young photographer’s political awakening and how she finds her voice amongst a tsunami of influences. As Nila discovers what it means to be the person you are, she too discovers what it means for that identity to be true.

Between philosophical dialogues and debates on aesthetics and Marxism, the novel is also consistently laced with gorgeous prose, pills, and parties occurring in almost every chapter. However, the real grit and grime of Good Girl lies in what goes unsaid. It’s buried in the silent glimpses and unspoken conversations that pass across the room of wealthy elites at a German fundraiser for Afghan dogs, or the news on a television that plays in the background of Berlin’s bakeries and cafés, or the quiet curiosity Nila feels while wandering Venice as “an uneasy tourist” in a foreign city for the first time—unsure of what to do and how to travel without a purpose or a family member’s funeral.

I spoke to Aria Aber, a poet, about her transition into prose and writing about a pulsing, provocative narrative of a girl growing up, falling down, and rising into the storyteller she was always meant to become

Kyla D. Walker: How did that transition from poetry to prose go for you? And why did you decide to write the novel?

Aria Aber: I started writing the novel in 2020 when I moved back to Berlin because I didn’t have any health insurance here in the U.S. I rented this small apartment in my old neighborhood there. And, of course, the world was shut down. I went on daily walks through the streets where there were all these clubs that I used to frequent a decade prior. And I was overcome with a sense of grief. On the one hand, for the world at large because of the pandemic and all the political upheaval that was happening that year. And on the other hand, it was a very private type of grief for a friend who had passed away. This sense, the inevitable sense of loss, activated my consciousness to an extent where I was experiencing all of these memories and sensations. Some of these chapters, or the first draft, of Good Girl really just poured out of me. Berlin, of course, is such a major character in the novel and being in the city physically led to me focusing the story in Berlin in particular.

I knew that it had to be a novel because I wanted to explore one character’s consciousness and their power dynamics with other characters, which is a little harder to do in poetry—at least in the poetry that I write, which is usually lyrical and focused on a very particular moment of epiphany or realization. And you can’t really maintain the sense of linearity—and political awakening that is important in the novel—within one poem. I also didn’t want to draw too much attention to the form of the book, which is why I decided not to write a novel in verse, which would have been a possibility. But a novel in verse always brings up the conversation of verse versus linearity, so prose allows you to hide the form a little more.

KW: There’s a line that says: “…Nabokov, on the other hand, was one of my favorite writers. He wrote with a lushness that embraced both beauty and irony. I always thought that the poetic intensity of his style stemmed from the fact that he was exiled in English, that he excavated the strangeness of English because he was a foreigner in it.” I just thought that shows how the book is conceptually concerned with the nuances of language: its barriers and the exclusivity and/or accessibility that language can create. Did you know from the start you needed to write this novel originally in English?

I personally think of beauty as something violent rather than just pretty and easily observed.

AA Yes. I always knew that this would have to be written in English, primarily because at the time when I started writing this book, I had made my career in the English language. But I also wanted to highlight the fact that the protagonist, because it is written in first person, is not native to the English language in order to draw attention to the textures and foreignness of the way that I deal with the English language in particular. There is a version of my life in which I might have written this novel in German. And I ended up translating it myself into German. However, all of my writing—be it poetry or fiction or even nonfiction—starts with a melody in my mind that I then translate into language. So it felt the most natural to me to write it in English. I was also invested in discussing two different types of immigrants in the book. On the one hand, we have Nila as this character who is a refugee and who is born in Germany. And, on the other hand, we have an American expat: Marlowe Woods, who sits on the other end of the spectrum as a voluntary economic migrant. I was interested in highlighting the differences of how they are being perceived by German society and the kinds of privileges or disadvantages each of them experience.

KW: My next question is tied to what you mentioned in the way that Nila sees herself throughout the novel. There’s this quote on page 13 that says, “Beauty was a tragic virtue, often abused because we are fooled by it. But I emanated something darker, something uglier. Like a fraught hunger for life.” Does this view of beauty leak into Nila’s photographic perspective on top of how she sees herself? And then does that tragic virtue of beauty carry over into how she selects which images to take?

AA: I think her understanding of beauty is skewed in some ways because she thinks of herself as ugly and undesirable and yet understands that she has some sense of power within her that’s attractive to other people—especially to someone like Marlowe, which I think is her voracious hunger for life. And beauty I personally think of it as something violent rather than just pretty and easily observed. I think of beauty as related to the sublime. So when you experience something that is beautiful, you are overwhelmed with the sensation of being at the receiving end of it. It might change something in you. It might awaken something in you. It might lead you down a very different path. There are many different ways in which this manifests within the conversations and the thoughts that Nila has in the novel. Beauty can be experienced, I think, when you read a book as well as just being at a party and surrounded by many people. Ultimately the beauty—in a very philosophical and aesthetic sense—that I’m talking about here is a beauty of change and experience that might unlatch something within you. But beauty, and that particular quote that you read, I think, relates to a sense of attractiveness that is more classical that she doesn’t feel connected to.

KW: Speaking of the sublime, too, I was very moved by the role that religion plays throughout Good Girl and this idea of how faith can act as a wall between characters and cause separation. It seems that Nila almost wishes her parents, and especially her mother, had been more religious while she was growing up. I’m curious how this desire and this hope of hers complicate the notion of being “a good girl” or in fact rebelling against that idea.

AA: There are two ways in which I thought about faith in the novel. The first is organized religion, which is not very present in Nila’s nuclear family and which she yearns for because she seeks structure and rules and a very rigid way of experiencing the world. As a person in exile, especially so early on, where she experiences her family to be kind of adolescents as well—not knowing which rules to carry over, which ones to implement—leaves her in a state of confusion and dislocation and only adds to the already quite destabilizing sensations of being a young person in the world. And on the other hand, I think my personal relationship to God and faith—and I instilled a little bit of that in Nila too—is the yearning to be part of something bigger than yourself and to dissolve yourself with a higher essence, which is actually very mystical in nature. She seeks God everywhere, and she doesn’t always find that connection even though, of course, raves and the excessive party culture that she fashions her life around, as well as using consciousness-expanding drugs, allow her to simulate a part of that religious feeling or oceanic feeling. I guess I was interested in the dichotomy between excess and abstinence, between strict rules and unabashed hedonism, and the two drives that psychologically manifest in Nila. She’s such a person of extremes. On the one hand, there is this feeling of Eros and the life drive that is leading her down a path of Dionysian filth. Then on the other hand, there is Thanatos, the death drive that makes her a little ashamed and wishes she didn’t exist at all. And the only times when she feels a certain amount of peace within herself and not absolutely overtaken by extremes is when she feels at one with the world, which ultimately is a moment of quietness that we sometimes experience in prayers.

KW: Throughout the novel, there are also these really interesting discussions of fascism, Marxism, aesthetic theory, and gentrification—with Eli studying architecture and Doreen’s activism, among other things that come up. In these scenes in particular, the socioeconomic statuses of the characters start to become clearer and the different ways their perspectives have been formed in Berlin. So, for these characters, what do you think might be the role of the artist within these larger political ideologies?

AA: I don’t think the novel provides a very clear answer on what the responsibility of the artist is. However, I personally—as a very political person—think that we do have a responsibility to the world at large regardless of whether we’re artists or not. I don’t think that aesthetics exist in a vacuum divorced from ethics. I think these two things inform each other constantly. And what I wanted to achieve in this novel is to create a character who does get changed by the world, right? Her artistic awakening is subtly linked to her political awakening at the very end. After the NSU violence is uncovered, she has this moment where she’s looking at a photograph of her father and his cousins and a couple of her uncles on a hill in Kabul, and one of the cousins has a camcorder in his hand. But for a moment, she thinks he’s holding a rifle. And that moment to her, I think, is crucial because it’s integral to the sensation that she is part of something bigger than herself. And I don’t discuss this overtly in the novel—what that means symbolically. Mistaking it for a rifle, mistaking it for a machinery of violence that could kill but is actually also just a piece of technology similar to the one that she has chosen as her art medium: a camcorder or a camera. So I do think that those two things are linked, and we at least owe it to the world to let it change us, even if as artists we don’t make art that would be considered political on the surface or didactic in any way.

KW: I wanted us to talk a little bit about what you mentioned about the violence in Berlin, the National Socialist Underground murders. That chapter was so powerful and tragic and especially moved me personally. I’m so thankful that you wrote about it. How did it feel and what was the experience like of writing about these real events that intertwined with the fictional? Was that history inescapable for this story?

AA: It was inescapable, one-hundred percent, because I wanted to write a story that is set at that particular time. And, looking back, it feels like a failed opportunity for Germany to wake up in some way and see itself as the country that it is, which has not very much evolved from where it was many, many decades ago, even though it prides itself on things such as memory culture and having accepted and dealt with its past, with its very racist past, in a good way. I just remember being a young person at that time and feeling the sense of confirmation for all the fears that I was raised with, that I had suspected to be true but hoped secretly might not be true. And I also knew that I wanted to write a novel that ends with an act of right-wing violence. Even before I had set on how, I had settled on the timeline and mainly because there aren’t enough, I think, of these kinds of stories and it is a fear that I always harbor that this is just around the corner and will happen. The way I fictionalized it in the novel is to include the burning and the murders: the burning of the bakery and the murders of those two Afghan bakers in Berlin in particular. Because most of the other things that I write about in the novel are actual occurrences, I wanted to dramatize it for the sake of the narrative and make it closer to Nila’s own life so that she would be forced to experience a political awakening. Having this story be more removed from her as it transpired in real life would have maybe not felt urgent enough for the psychology of this character in particular because she’s so reluctant to accept herself as a politicized body within the world that she inhabits. But also, I didn’t want to spend too much time discussing the murders of real people because it’s still very close to me, and I wanted to be respectful to the actual victims and not sensationalize their deaths, which is why I chose to create a fictional event at the very end. It is such a painful moment in German history.

KW: Now diving a bit deeper into the relationship between Nila and Marlowe, there’s this sense of the shadow of exile that haunts Nila and her parents after they’ve left Afghanistan and are starting their new lives in Berlin. And we talked a bit earlier about this as well—how Marlowe was also an immigrant in Germany though comes from a very different background, but still finds some similarities with Nila. Later, the relationship turns out to be quite toxic and abusive. I’m curious how geopolitics might be playing a role in this particular relationship. How have war and imperialist forces affected the dynamics between them, if at all?

AA: Interestingly, when I first sketched out the novel, I was inspired by Nabokov’s treatment of Lolita. He said, when he set out to write that book, that he was thinking of the characters Humbert and Lolita as the Old World versus the New World—with Lolita representing America and Humbert representing Europe in some way, and how they interact with each other. I don’t think that ultimately manifests in the novel in any productive way, but it’s an interesting framework to think of as a surface, right? And when I set out to write Good Girl, I thought about including this American character in order to also symbolize American imperialism and how it has affected the world and Afghanistan in particular at that time.

This was a great starting out point, even though it became less and less relevant the more fleshed out Marlowe as a character became. I think it definitely plays a role in the ways they interact with each other because he has all of these privileges that he is more or less unaware of, right? He speaks the lingua franca of the world. He’s a white man. He can move through rooms without being detected as a foreigner, which Nila cannot. And yet, at the same time, there is this almost paradoxical yearning for America within Nila herself, but also in her father and her family who are attached to this very antiquated idea of the land of freedom, where anything is possible, which they don’t see for themselves in Germany… I was interested in the nuances of that and how they manifest in her family and why she’s attracted to Marlowe in particular. Part of it is that he is from California, which is the state that her father idolizes so there is that connection and an inherited fascination with the landscape of the West that he brings into her life. And on the other hand, he is also symbolic of everything that she yearns for in terms of artistic freedom and a life that is not dictated by rules but is rather lived in freedom.

One other thing that is quite interesting to me is that Nila, early on in the novel, says that she sees an image of Marlowe in a magazine beforehand and that she remembers that photograph which has made a big impact on her. So she’s quite literally enamored of his image—the surface and everything that he represents there. And the more she gets to know him, the more the image crumbles. He becomes weaker and less successful, or less confident, whereas she gains a sense of confidence and artistic voice. So, their arcs are opposed to each other, which psychologically is very interesting, even though it doesn’t necessarily function with the parallelism of the nation states and how they represent those.

KW: Throughout the book there are several mentions of writers that Nila is reading and being influenced by. Who are some of the writers you were influenced by while writing Good Girl and do they overlap with Nila’s?

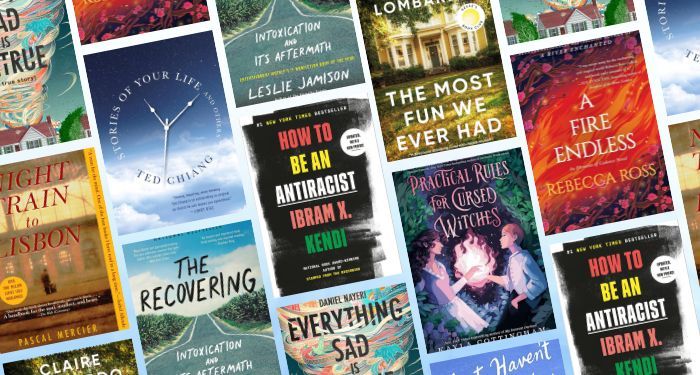

AA: Interestingly, the writers that Nila mentions were not part of my personal syllabus that I used while writing Good Girl. Because I don’t have an MFA in fiction and didn’t have classical training, I had to teach myself how to write a novel. I read a lot of Jean Rhys and Marguerite Duras and James Baldwin because all three of them write these protagonists who are adrift in various cityscapes. So urban melancholia was something that I was trying to learn how to bring across on the page, and at the same time, also this feeling of insatiable desire and erotic fulfillment that they also often seek and don’t always manage to find in other people. So, the sense of loneliness and being adrift in a city was something that I learned, or tried to copy, from those writers.