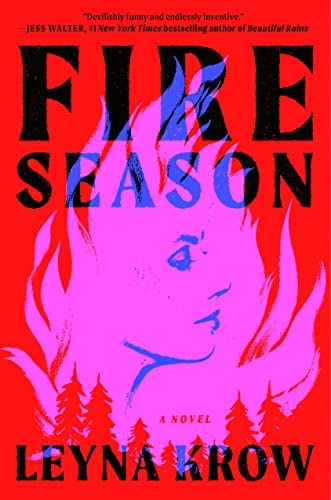

The central character in Leyna Krow’s debut novel Fire Season is a schoolteacher-turned-prostitute-turned-swindler named Roslyn, who happens to be in possession of certain supernatural abilities. It is 1889 in the frontier town of Spokane Falls. At first, in a stroke of structural genius, Krow hides Roslyn from us in plain sight. She appears in the first sentence of chapter one, an offhand reference in our introduction to one of her johns, a put-upon banker who occupies our attention for the first act of the novel. Krow does not yet ask us to notice Roslyn, an alcoholic prophetess. Instead, Roslyn skulks about in the corners of other characters’ stories until the last third of the novel, at which point she drifts to centerstage and everything falls into place around her.

The story of the American West has conventionally been the story of a certain kind of man: self-possessed, independent, and therefore powerful. The first two acts of Fire Season orbit around two such men: the put-upon banker and a self-made conman. With Washington Territory on the cusp of statehood, these two opportunists leverage a city-consuming fire and the self-interest of those around them to their own profit. All the while, Roslyn simmers in the wings.

Between chapters, Krow inserts tiny interludes focused on Roslyn and, between acts, longer digressions focused on other women who, like Roslyn, occupy the frontier as outsiders. They are, Krow reminds us, a “certain kind of woman”: self-possessed, independent, and therefore dangerous. The first such interlude (the prologue), like the novel, seems to focus on a man, a variety of nineteenth-century public intellectual of dubious credibility, intent on shocking his audience with his claim that the most pernicious of evils threatening their tenuous social fabric is embodied in none other than his own mother, who sits caged on the stage beside him, knitting. The audience is aghast. One man shouts out, “Let the woman speak for herself!” And when she speaks…

Here is another trick Krow has up her sleeve: From the outset, the novel presses against our understandings of the world she is rendering, our impulses to categorize it. Is this some species of historical realism or pure fabulism? She constructs the past to leave ample space for doubt. Fiction is, of course, uniquely positioned to reorient a masculine history committed to sidelining the lives of women, and this is precisely the subversive magic Krow is up to here. Krow’s first book, the luminous and funny story collection I’m Fine, but You Appear to Be Sinking, charts this fracture line between realism and fabulism. When I discuss this book with my creative writing students, as I often do, our conversation pulls toward a discussion of magical realism, and we recall that that form has for decades given voice and story to marginalized communities pressing against hegemonic and colonialist narratives. Though Fire Season paints with a quieter kind of fabulism than Krow’s earlier work, it finds new purpose in the device.

Here is another trick Krow has up her sleeve: From the outset, the novel presses against our understandings of the world she is rendering, our impulses to categorize it. Is this some species of historical realism or pure fabulism? She constructs the past to leave ample space for doubt. Fiction is, of course, uniquely positioned to reorient a masculine history committed to sidelining the lives of women, and this is precisely the subversive magic Krow is up to here. Krow’s first book, the luminous and funny story collection I’m Fine, but You Appear to Be Sinking, charts this fracture line between realism and fabulism. When I discuss this book with my creative writing students, as I often do, our conversation pulls toward a discussion of magical realism, and we recall that that form has for decades given voice and story to marginalized communities pressing against hegemonic and colonialist narratives. Though Fire Season paints with a quieter kind of fabulism than Krow’s earlier work, it finds new purpose in the device.

The full extent of Roslyn’s supernatural powers—the full extent of Krow’s commitment to the fantastical—remains veiled from us. As we move through the first two acts, our impulse is not altogether unlike the audience in the prologue. Let the woman speak for herself! And when she speaks…

*

In 2007, newly arrived in Spokane from points east, I found myself seated at a bar next to the mustachioed, cattle-running local literary fixture John Keeble. I was a green incoming MFA student weaned on the regional literature of the South, where I grew up within easy driving distance of Flannery O’Connor’s Andalusia. Intent on proving my studiousness even over the din of the bar, I turned to Keeble and asked whether there existed a regional literature of the Northwest as distinct from, say, the Louis L’Amour/Cormac McCarthy spectrum of Western literature. Like many young men in graduate programs from time immemorial, my questions were often not questions at all but opportunities to flex what I did not yet realize was ignorance. Keeble nodded, slowed his breath, and began the project of introducing me to the obvious answer in the form of writers like Richard Hugo, Gary Snyder, Barry Lopez, and David James Duncan—writers who, like Keeble himself, render the region through a certain kind of deeply-human, ecologically-aggrieved mannish realism that distinguishes itself from the more widely-known corpus of the West in its stylistic and spiritual connection to the literature of East Asia. This body of Northwest literature is quieter and more contemplative, swapping gunfights for fly fishing, action for imagism.

And yet it is—like the L’Amour/McCarthy school and like the history of the region itself—still aggressively masculine. In Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams, the frontier ethos of the early twentieth-century Northwest is one of men “hungry to be around… massive undertakings, where swarms of men did away with portions of the forest and assembled structures as big as anything going, knitting massive wooden trestles in the air of impassable chasms, always bigger, longer, deeper.” Even in its quietest moments, the Northwestern tradition can feel like the literary equivalent, to borrow Johnson’s phrase, of “knitting massive wooden trestles in the air of impassable chasms.” Into this, Krow’s novel offers a welcome feminist reorientation of the regional literature, aligning with and extending the path carved decades ago by Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping and, more recently, Sharma Shields’s The Cassandra.

And yet it is—like the L’Amour/McCarthy school and like the history of the region itself—still aggressively masculine. In Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams, the frontier ethos of the early twentieth-century Northwest is one of men “hungry to be around… massive undertakings, where swarms of men did away with portions of the forest and assembled structures as big as anything going, knitting massive wooden trestles in the air of impassable chasms, always bigger, longer, deeper.” Even in its quietest moments, the Northwestern tradition can feel like the literary equivalent, to borrow Johnson’s phrase, of “knitting massive wooden trestles in the air of impassable chasms.” Into this, Krow’s novel offers a welcome feminist reorientation of the regional literature, aligning with and extending the path carved decades ago by Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping and, more recently, Sharma Shields’s The Cassandra.

In The Cassandra, Shields—like Krow, a Spokane-based writer—recasts the eponymous Greek prophetess as a young woman in 1945 who works as a secretary for the Women’s Army Corps at the Hanford Research Center, where plutonium is being enriched for the Manhattan Project. Here, Shields reconstructs a woman’s voice within a historical moment bent on violence, and like Krow, she adopts a canvas that balances a deep understanding of its historical setting with an impulse toward fabulism. In this way, both writers build novels that speak beyond the confines of historical realism to address larger questions.

Krow’s project mines this territory in ways that expand upon Shields’s vision in two important ways. Shields’s The Cassandra is, like Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, a tragedy with all its attendant darkness. This is necessary to Shields’s subject matter. Krow—writing about a less cataclysmic but undeniably formative moment in American history—manages a tone that inserts, if not levity, at least a kind of fierce playfulness that is well-suited to reimagining a West that is at once wilder and more intimately human than reported. More revolutionary than that, though, Krow embeds into Roslyn’s story a way forward.

Krow’s project mines this territory in ways that expand upon Shields’s vision in two important ways. Shields’s The Cassandra is, like Aeschylus’s Agamemnon, a tragedy with all its attendant darkness. This is necessary to Shields’s subject matter. Krow—writing about a less cataclysmic but undeniably formative moment in American history—manages a tone that inserts, if not levity, at least a kind of fierce playfulness that is well-suited to reimagining a West that is at once wilder and more intimately human than reported. More revolutionary than that, though, Krow embeds into Roslyn’s story a way forward.

Late in Fire Season, having kicked alcohol and found a viable way to practice her prophetic gifts, Roslyn reflects on the difference between herself and the shiftless men around her. The difference, she discerns is “the difference between a burden and power.” Her supernatural gifts are a burden to her—as there are to Shields’s iteration of Cassandra—whereas they would be power in the hands of a man. How to free herself from this burden? Simple: “Act more like him.”

But then she doesn’t. Or she does, but only to a point. She takes what she wants and does what she wants with what she takes. The difference is that, unlike the no-account grifters she supplants, Roslyn wants to move through a burning world in a way that carries freedom to others as well. In this way, Krow manages to write a novel that is both apocalyptic and optimistic.

If quiet fabulism like Krow’s inherits the tradition of magical realism, giving voice to the voiceless, it is worth hoping the tradition carries forward. In Northwest literature, Blackfeet and A’aninin poet and novelist James Welch occupies this stylistic space in his 1986 novel Fools Crow, as have many Indigenous writers in the Southwest and Great Plains. Krow, Shields, and others contribute a needed feminist perspective, but there is still much work to be done to diversify the Northwestern canon.

If quiet fabulism like Krow’s inherits the tradition of magical realism, giving voice to the voiceless, it is worth hoping the tradition carries forward. In Northwest literature, Blackfeet and A’aninin poet and novelist James Welch occupies this stylistic space in his 1986 novel Fools Crow, as have many Indigenous writers in the Southwest and Great Plains. Krow, Shields, and others contribute a needed feminist perspective, but there is still much work to be done to diversify the Northwestern canon.

*

As I write this, the smoke is clearing following another week of late summer wildfires in the Northwest. This summer has not been bad, nothing compared to the summer of 2017 when wildfire smoke blanketed the Northwest for months and all our outdoor plans were scuttled even before Covid taught us everything is imminently cancellable. That summer it seemed like all of Washington was on fire. We snuck outside to watch the solar eclipse through a scrim of smoke. It is tempting to draw a connection between the fire seasons that fuel the various shenanigans of Krow’s characters and those that darken the skies of our summers here in the Northwest in recent years, but that suggests something narrower than what Krow has in view. Our region may be burning now, and certainly we have seen our share of human malfeasance, negligence, and ignorance fueling the fires. Still, Krow seems less concerned with the fires themselves—there have always been fires of one sort or another—than with what the fires reveal in us.

When she finally shakes herself free from much of what encumbers her, Roslyn pays a visit to the Portland Zoo, which calls the reader back to the prologue and the shyster intellectual’s knitting mother who, when she speaks, calls down a thunderstorm so momentous that it frees the inhabitants of the Philadelphia Zoo. A bull moose bursts through the doors of the lecture hall. Outside, “ostriches, flamingos, tapirs, spotted elk, and a black leopard with yellow eyes ran west along Walnut Street.” Standing alongside the bear pit at the Portland Zoo, Roslyn trains all her supernatural abilities on the ursine inhabitants and exhorts them to “Climb the walls and leave.” We do not see them walk free, but in calling them forth, we see something at least as remarkable: Roslyn walking forward into a burning world, calling her fellow creatures to cast off their shackles.

.jpg)