Electric Literature recently launched a new creative nonfiction program, and received 500 submissions in just 36 hours! Now we need your help to grow our team, carefully and efficiently review submitted work, and further establish EL as a home for artful and urgent nonfiction. We’ve set a goal of raising $10,000 by the end of June. We’re almost there! Please give what you can today.

“From the Great Above she opened her ear to the Great Below.

From the Great Above the goddess opened her ear to the Great Below.

From the Great Above Inanna opened her ear to the Great Below…

Inanna abandoned heaven and earth to descend to the underworld.”

– Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth, translated by Wolkstein and Kramer

My future self sets the briefcase on the lunch table and clicks it open, revealing two syringes of silver liquid. It’s been eighteen, maybe twenty years since this dream. Future me has long auburn hair, a terrible dye job I won’t attempt until after college, in the bathroom sink of a ratty apartment. They pull a syringe from the briefcase, tap out the air, and say only: A vaccination against what’s to come.

Most of us don’t have the luxury of believing ourselves entitled to the future. Most of us—especially people of color living in a white supremacist society and world—are constrained to the past, if we are even allowed a past. The world is always ready to write of us in the past tense.

You might ask why I’m writing about trans immortality when, every day, every month, every year, more trans people are dying than ever. Let me put it to you this way. On July 9th 1975, thirty-three year old Dutch performance artist Bas Jan Ader set off from Cape Cod to cross the Atlantic in a thirteen-foot sailboat named the Ocean Wave. Nine months later, the unmanned vessel was found floating bow-down off the Irish coast. Ader was never found. His absence itself became the second part of his unfinished triptych “In Search of the Miraculous.” I suppose that if he hadn’t risked death, even had he arrived to England, his arrival would not have been a miracle. Miracles are only considered miracles if terrible things would have happened in their absence. The cost is proportional to the miraculousness.

The world is always ready to write of us in the past tense.

Terrible things happen all the time, I assure you, of which most of us know nothing. My question is what we do with unanswered prayers. Any history I tell of trans life, carrying that life into the future, will be incomplete because most of our histories are unknown, erased, or illegible to the cis arbiters of historical knowledge. No: I am not interested, here, in salvaging a recountable history. I want to know what happens to those of us whose names aren’t treasured up in books or social media or candlelight vigils or other people’s mouths, because most of us suffer without ever being immortalized. Like a mycelial network, we are connected by the thing that underlies us, but we may not realize it. One of us springs free of the earth in a field of potatoes; another parts the slipsoil of a mountainside, seeking siblings. We are ancient, though I’m not sure it matters. The oldest living organism is a lichen, a composite of an alga and a fungus, pulsing away undisturbed on a rock in Greenland for over 8000 years, growing only a centimeter in the course of a century.

A century!

We have the internet now, and all its fascists, and there are as many futures and pathways to them as you can possibly imagine. The future isn’t linear; it’s branching, various, multiplicitous as the lichen. What I want to know is what we do with a past, dense and painful and complicated, that refuses pat eulogy. I want to know how to hold the unknowable weight of trans suffering without erasing its hope. How many of my transcestors spent entire lifetimes bobbing along sweeping hearths, spreading duvet covers, slicing onions to feed a man and a child—lonesome and absorbed and convinced we were the only ones?

Future Me must have known about the basement rental, about the house centipedes and the boyfriend who kept a long knife in the bedside drawer. Future Me must have known about the bright, lonely apartment after that one, the man who hung crosses above all the doors. Maybe you’ve heard of the lesser known Saint Agnes, the one from Rome, the patron saint of girls, chastity, virgins, gardeners, and victims of sexual abuse. When she refused the advances of her wealthy suitors, she was condemned to be dragged naked through the streets and raped in a brothel. Her hagiography claims she prayed as she was dragged, that her hair grew so long it covered her, that her would-be rapists were struck blind. Consider the cloak of her hair, the unburnt stake and pyre, the soldier unsheathing his sword. Consider the dozen or so men rubbing in terror at their eyes, the cries of darkness, their sudden night. And Saint Agnes standing there, thinking, now? Now you come?

The Sumerian goddess Inanna, who descended into hell to offer her condolences to her sister Ereshkigal after the death of her husband, the Bull of Heaven, was said to have the power to change the gender of those who worshiped her, and people who might today be called transfeminine—the galli—performed rituals in her temples. In the Sumerian poem that describes her descent into the underworld, Inanna enters the throne room of her sister Ereshkigal, naked and bowed low. Inanna is not welcomed, but struck. Her body becomes meat, emptied. Her corpse is hung from a hook on the wall. For Inanna, time stops.

You might ask why I’m writing about trans immortality when, every day, every month, every year, more trans people are dying than ever.

When my beard started growing in, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had been returned to my sixteen-year-old body. Like many trans people, I joked I’d become a vampire. My skin grew soft and acne-spotted; I rode my bike at night for miles and miles. The problem was not that I was thirty-three according to my birth certificate, but that sixteen was not a good age for me. There were things that happened to me at sixteen that I had worked very hard to forget, and apparently they lived in that pubertal body, the one I’d come back for at last. I washed my face twice a day, relived the desperate, lonely knot of driving past a high school boyfriend’s house, the one everyone knew was gay before I did. This is the boyfriend who once wrote me into a story as a muscular, effeminate man flipping his dark hair in the wind. If I think too hard about the details of this story it seems to wink out of existence, as though it is too incredible to have happened. We had a bad breakup. I thought love was a boulder and clung to people to convince myself that I existed. I needed the version of myself that existed in this boy’s eyes. Without it, I feared I’d slide off the face of the earth. Which is very nearly what happened.

In a fable whose roots and versions span South and West Asia and parts of North Africa, a child is girled at birth, grows into an adolescent, and is betrothed to a man. The adolescent—still a child, really—prays to God to be changed into a boy.

Instead, a jinni answers. The jinni tells the child they may swap genders, so long as they swap back later. The child receives the jinni’s penis and testicles, presumably what is meant by the word sex, and grows into a man. The man falls in love. The man is happy. He dreads the moment when he will have to swap back. But one day, the jinniyah returns. I have broken the seal of the package with which I was entrusted, she says. She has become pregnant and cannot swap back.

As a child I did not think to want a penis. I understood my body as a thing to be redeemed, like sinners. Something in me had been opened by force, and I blamed this violation for God’s great silence. God, I would pray outside my mother’s church with my eyes shut tight, God, come. There was no rest of the prayer.

Bodies may be designed to live, but they aren’t designed to last. Shortly after, at ten, I began to flood two and three overnight pads. I bled through the mattress. I missed school. I learned to swallow ibuprofen before it turned bitter. I learned the mercy of the body, that too much pain will make you pass out. I learned you can live in the land of pain, be hung from its rack and not die.

I learned you can live in the land of pain, be hung from its rack and not die.

Scientists say endometriosis can be as painful as active labor, even a heart attack. I saw many, many doctors. A partial list of the doctors’ suggestions: motrin, tylenol, squid ink, heating pads, meditation, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, birth control, prayer, valerian, chamomile, ginger, oxycodone, pregnancy. One day, I thought, I will be dead. Then I will not be in pain.

Awareness of death is an awareness of the future. Maybe your particular sick will not kill you. Still, other people design futures and fail to invite you.

Genetics, I learned during my doctoral studies, tells us that immortality is to ensure that one’s offspring see the future—that is, unless you are a cancer cell, or a clump of endometrium on the run, clinging to bowel or bladder like a bank robber holed up in a roadside motel. I never had the right body to be a child. I didn’t want to become someone else; I wanted a different history, which would have ensured a different future. As a chronically ill trans child and, now, a chronically ill trans adult who doesn’t want to use my body to carry children, I will never be my parents’ treasured immortality. I only know what it means to be the ghost of their want.

What do I do with the version of myself that remains suspended in pain? What do I do with the past selves who live in this body that slips through time? The more famous Saint Agnes, Chiara’s sister, fled to her sister’s convent to avoid a marriage. When the family came to yank her from the altar, her body became heavy as iron, and she was saved. In the fable of the jinn, the man is happy. He keeps his penis. It is a miracle.

In fairy tales and epics, two things lie beyond the realm of the human: the demonic and the divine. Stories of miraculous gender transformations occur in both fables and historical documents going back thousands of years. In a 2015 doctoral thesis entitled “(Trans)Culturally Transgendered: Reading Transgender Narratives in (Late) Imperial China,” scholar Wenjuan Xie catalogs events of girled children transformed into boys or men because of their families’ piety or sacrifice as far back as 487 BCE. Here, too, though, bodies like mine are objects, rather than subjects: typically, the family wants a son in place of a daughter.

Bodies like mine are objects, rather than subjects.

French trans artist and art historian Clovis Maillet writes in Les Genres Fluides about how medieval convents were havens for white transmasc and gender nonconforming people assigned female at birth, though the same didn’t work for transfems. To strive for the divine was to strive for maleness. In Europe in the Middle Ages, to be male was to be human, and therefore neutral; in a way, only women “had” gender as a modifying trait. In certain illustrations, women were labeled as a kind of animal. Because of the link between masculinity and virtue, the (white) body was sometimes deemed irrelevant. In what feels like a prelude to modern Western conceptions of the split between gender and the body, Saint Francis loses nothing of his manhood when Santa Chiara dreams of being breastfed by him. Italian art historian Chiara Frugoni recounts the story: “The saint drew out from his breast a teat and said to the virgin Chiara: ‘Come, receive and suck.’ And sucking it, that which flowed from it was so sweet and delectable, that she could in no way explain it… and taking in her hands that which remained in her mouth, it [the milk] seemed to her gold so clear and shining that all was seen in it, almost as in a mirror” [translation mine].

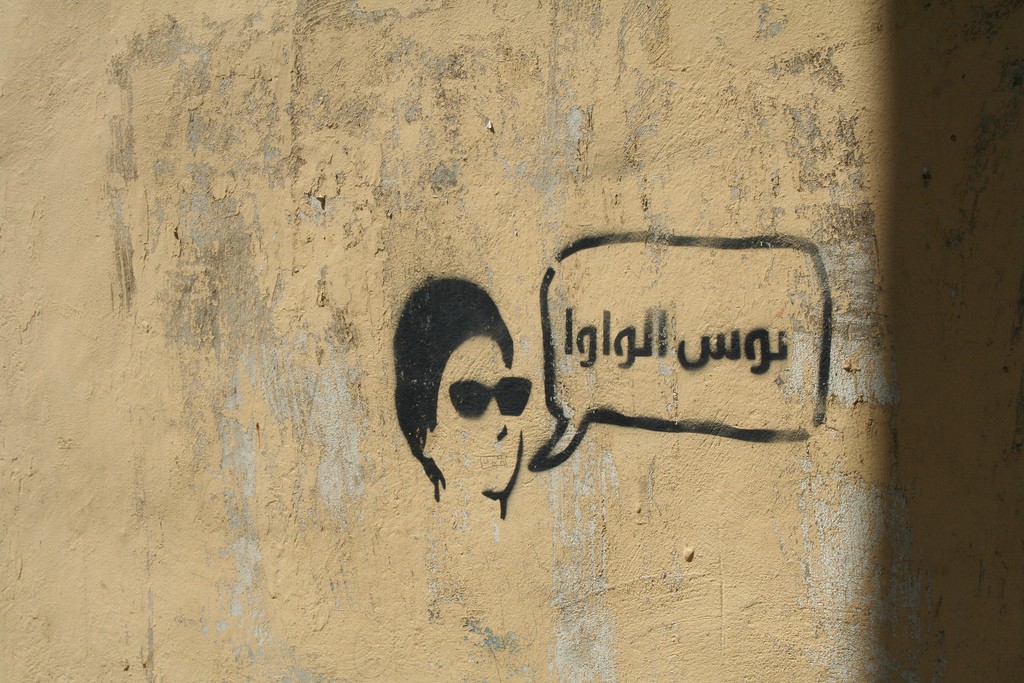

The list of trans saints is already long and well documented. And though other people’s eyes are not a prerequisite for existence, there is something profound about being looked into like Francis’s golden milk. Chaza Cherafeddine, in Divine Comedy (2010), photographed Beiruti trans women and cast them as the fantastical buraq, the winged, human-faced steed of the Prophet, peace be upon him, dazzling in emerald and ruby feathers. That said, on the ceiling of the dome of the cupola of the Cathedral of Florence, Vasari’s and Zuccari’s angels of the Last Judgment are white twinks with flat chests and smooth cheeks, while their demons are brown, purple, green, hairy as goats. Their bodies are adorned with breasts and penises, their fire-tipped spears plunged into the nether regions of tortured souls. In this version of the universe, my friends and I are having the world’s most epic orgy in hell.

I won’t romanticize the survival of my transcestors. Had I been born a century earlier, a centimeter in the history of lichen, I may not have survived. In this version of my life, I am declared possessed by male jinn, seized by malevolent spirits. In this version of my life, I write out passages from the Qur’an, submerge them in water, and drink the dissolved ink. In this version of my life, I pray.

The Catholic Church believes in the concept of a victim soul, those chosen by God to suffer for the redemption of humankind. This isn’t something the church declares; the person alone knows. Santa Gemma Galgani of Lucca was the daughter of a Tuscan pharmacist, orphaned at eighteen after her father, mother, and brother all died of tuberculosis. The disease would take her, too, at twenty-five. She is the patron saint of pharmacists, parachutists, orphans, those with back pain and migraines. She was said to levitate and received the stigmata at twenty-one, a precocious, teacher’s pet saint.

A victim soul.

Everyone knows how to be happy but you, I scolded myself for much of my twenties, because I believed happiness to be an act of will. The only video that exists of me dancing was made at a residency on Ohlone land, to Oum Kulthum. Minutes before, an Argentinian artist had taken a pair of scissors and cut into my white tee shirt while I moved, turning my sleeves into curtains of knots, creating a keyhole across my sternum and a slash on each flank. I didn’t ask him to do this, so he can’t know I want to excuse myself from my life. In the video, you can’t tell. I’m not a good dancer, but in this video, I look like a girl who knows how to dance. I wanted to make a copy of myself that could live without me in it. I don’t appear in the eye of the camera. I am buried beneath it like a seed.

Stories of miraculous gender transformations occur in both fables and historical documents going back thousands of years.

Little more than a year after the video, out as trans to my close friends and partner but still trying to convince myself I can live with my dysphoria, I’m walking through the city of Lucca after a couple of glasses of wine, having forgotten all about Santa Gemma. It is two days before Christmas. Though I won’t unravel my feelings about hormones for another two years, I keep telling myself I will find a way through my exhaustion and dissociation. I try to convince myself that I could even give birth, though it’s unclear whether my body is capable of pregnancy and I don’t want to find out. Doctors tell me testosterone will destroy my fertility, though this isn’t true, and I’ve just found out it’s illegal for same sex couples to adopt in my partner’s country, Italy. Maybe I could go away in my head, I reason, smile at strangers. I’d shut my testosterone canisters in a cabinet. I’d stay very still. I conjure a hypothetical life in which I have a partner so grateful for babies that they look at me every day and smile. They smile so hard they cry, smile so hard they have to go to special doctors because their face begins to hurt from smiling. I know you can survive your body being taken from you. People have been looking through me like a window all my life. Courage, hold your breath. Glaze over like a lake in winter. You won’t feel a thing.

The wine dulls the cold, but still we turn into a narrow street, out of the wind. A portrait hangs over the lintel of a door. I recognize Gemma’s upturned gaze, her black frock and folded hands. I sit down on the steps of the house opposite and command myself to cry. I cannot. I berate myself for being tipsy and unhealed. In this house, a saint’s hands and feet began to bleed. God passed through Gemma and transformed her. I’m still waiting to be touched.

After the meat of Inanna’s body is hung on the rack, Ninshubur, her handmaiden, dresses herself as a beggar. She tears at her eyes, her mouth, her thighs. She sets out for Nippur and petitions Enlil at his temple, who denies her. She goes to Ur, to the temple of Nanna, who turns her away.

Finally, in Eridu, Enki grieves for her plea. Father Enki picks bits of soil from under his fingernails and transforms them into a kurgarra and a galatur, beings “neither male nor female.” Giving them the food and water of life, he tells them: Go to the underworld. Enter the doors like flies.

The next time Future Me came, I dreamed of him in a nightclub. I wore a sparkly purple mini dress I’d recently given away to another trans friend and my three and a half inch black plastic heels with the cork platforms. He looked dangerous and sleek, and I cursed him. God, I thought, I am going to be beautiful, then bolted, terrified, through the crowd. If I stared too long he might leap down my throat, sprout black hair on my thighs, swell the muscle in my shoulders, unfurl the veins in the backs of my hands. An ecstatic fire would enter me, a joy I could not permit myself under any circumstances. The pain would kill me, I feared, were I able to feel anything else.

Santa Lucia is the patron saint of the blind, but also of a long list of others: martyrs, saddlers, stained glass workers, the town of Perugia, even (God help us) authors. In the northern Italian town where I now live with my partner, Santa Lucia’s feast day used to be a bigger celebration than Christmas. Something real still remains of her, or at least it used to, when the saint used to roam the streets of little Bergamasco towns in a long dress and veil of white lace. Everyone knew the one who came to the elementary school was fake, my partner tells me, like shopping mall Santa. But the one who floated through the town couldn’t be written off. The children would tell her the gifts they wanted as she passed, and Lucia, silent, would incline her head. Several women took turns wearing her white dress. The body was a door for the sacred. Lucia’s veil made a woman into something else.

According to legend, Lucia was a Sicilian woman from Syracuse who was martyred when Diocletian gouged out her eyes in the third century. Her feast day was originally celebrated on the winter solstice, her blindness symbolizing the darkness of the longest night of the year into which she—the name Lucia itself derived from the Latin lux—bore the light. Only in the fifteenth century does she begin to appear eyeless, bearing two lidless orbs on a plate. Francesco del Cossa depicts her lifting a delicate stem from which another set of eyes blossom, like lilies.

The light would have been different in the years my partner saw Santa Lucia. The streetlamps were all sodium vapor then, yellow-orange, not the penetrating blue-white of LEDs. When I left home for college, the only blue lights were the emergency call buttons scattered around campus. There was one trail where there was no blue light, a trail leading between certain campus buildings and certain dorms through a small wood. The boys called this the “rape trail.”

Most cities have LED streetlamps now, and the night doesn’t look the same. The light has changed, disappearing the shadows I remember. Yet I still fear the trees.

I meet Future Me again at a barbecue. In this dream, he has his arm around my partner and a cup in his hand. He is laughing. He has denser stubble, a more angular jaw. I am jealous of him because he is happier, more charming, more beautiful than me. I am jealous of him because he lives in a beautiful future into which I cannot follow.

I understood my body as a thing to be redeemed, like sinners.

He comes to me in my mid-thirties, as governments around the world are doing everything in their power to eliminate trans life and parenthood via sterilization requirements, abortion bans, smearing us as pedophiles, making it illegal for queer and trans people to adopt, listing us incorrectly on our children’s birth certificates (and our own documents), and criminalizing life-saving healthcare for both trans children and, increasingly, adults. He comes to me as rightwing politicians attempt to outlaw the imagining of trans futures.

Future Me is slowly replacing Present Me. I’m not saying I was ever another person. I’m saying some part of me, the pilot light version of myself, kept me alive when living was too painful to do. For years I assumed everything that happened during those dissociated decades was lost, mercifully. But once I began testosterone, memory surged up from deep freeze. I once tried to re-envision my childhood traumas with my present body, and for a few seconds I closed the distance on my past self with vicious clarity: there I was, the boy and his pain, and finally, terrifyingly, I understood myself to be human. But the feeling was slippery; it fell away at once, and I lost it again. To dissociate is to become a mirror, the surface of a windless lake. Who, exactly, had been raped? Was a younger me still trapped there, waiting for a miracle?

Time is a spiral with its layers pressed together. Ibn ‘Arabi describes time as an eternal circle. All points on the circle, though distinct, remain in touch with eternity. The past is not separate from the future, but part of it. If the past slips into my present, I see no reason why the future shouldn’t slip back to visit me. Only the future is slippery, too. A transition, like a novel, is a risk. The real dislodges the fantasy, destroys it, debases it by existing. But the real is tangible, at least. You can work with the real. A transition, unlike the fact of being trans, requires you to choose yourself. I would only learn later that it also requires you to relinquish your fantasies not only of who you will become, but who you’ve been.

My transition will never be finished. I am not following a line from one binary gender to another, but moving laterally, diagonally, inwardly, spiraling through time in my ever-changing, ever-returning body. Even melancholy, in this skin, is sweet. The boy I exiled comes alive in my face. I am eroding a fantasy of who I thought I was, crumbling it like wet sand, revealing the boy banished to the self behind the self. The boy who kept very still, frozen, so we might one day live.

The boy I exiled comes alive in my face. I am eroding.

If what Ibn ‘Arabi says is true, then I possess immortality—like eternity—in this very moment, in my very body. Listen: I am trying to arrive at the miracle by the door of my trans flesh. I will not believe them when they write that I am dead.

The kurgarra and the galatur find the queen of the underworld naked and in labor, moaning, her hair “swirled around her head like leeks.” When she groans Oh! Oh! My belly!, they groan, Oh! Oh! Your belly! She cries, My back! They cry, Your back! Your heart! Your liver!

Bewildered, she asks who they are to share in her pain, offering them the river and the fields as a reward. But they ask only the corpse hung on the wall, and it is granted.

The kurgarra sprinkles the food of life on the corpse.

The galatur sprinkles the water of life on the corpse.

Inanna rises.

If immortality is a possibility that exists from moment to moment, perhaps practicable immortality is a hope in the future as a reachable place. Once I writhed in bed, wondering if the pain—like the future—was all in my head. I clasped my belly and stared at my father’s paintings. I, too, wanted to be an artist. I didn’t have the word trans then, but I was convinced I would die young. I believed the only way not to disappear was to make art, as though by making something beautiful I could locate God. Bas Jan Ader set off from Cape Cod in a thirteen-foot sailboat and was never seen again. Maybe the beautiful future, like eternity, is an asymptote we approach only once we accept that we may never reach it.

My partner, Italian visual artist Matteo Rubbi, once made a work called “Il Muro,” the wall: a single person supports a wooden wall that would otherwise fall, holding it upright with the force of their outstretched arms. I can’t pluck my past selves from the rack of pain, just as I will never know most of the trans siblings who were afforded no miracles. I came back for myself, as we come for each other. The self who haunts me teaches me that our beautiful futures will not abandon us so long as we hold them aloft, like my partner’s impossible wall, with our hands.

This, at least, is what I tell myself, and plant my feet.