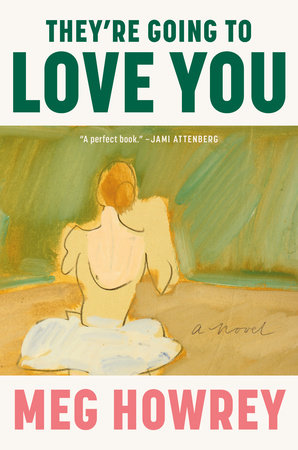

Before she became a novelist, Meg Howrey was a ballerina. She danced professionally with the storied Joffrey II Company and performed with several other ballet companies, as well as in various theater productions. It’s no surprise, then, that her fourth and most recent novel, They’re Going to Love You, is her second work of fiction set in the ballet world.

In Howrey’s 2012 novel The Cranes Dance, her sister protagonists live and perform in the injury-laden, drug-fueled, and precarious world of working ballerinas. The sisters, who are young adults, have never known any other life. They’re Going to Love You, on the other hand, is narrated in the first-person by Carlisle, a choreographer in her forties who finds herself estranged from her dying father and his partner James, both of whom spent their lives dancing. Dancers and choreographers work hand in glove, their relationship akin to those of musicians and composers or actors and playwrights. Theirs are separate but codependent art forms: one formulates a singular vision while the other implements it.

Exploring not just dancing but specifically choreography from a woman’s perspective was important to Howrey. In an interview with her earlier this year, she told me that at the time this novel is set, 2017, “the dance world was rife with articles asking where were the female choreographers.” Howrey would have preferred a different question: “Where is the recognition and support for female choreographers already toiling in the vineyards?”

They’re Going to Love You is a dance novel, but it is fundamentally a family drama that considers what makes relationships work and what makes them implode. The trappings of the dance world and Carlisle’s musings about her choreographic commissions form a rich tapestry around these themes. Howrey says she did not start her book from the standpoint of an imaginary ballet star, but from the point of view of “someone who was having to do what a lot of working artists need to do—hustle, take jobs because you need to make rent and car payments, or keep your health insurance.” This grounding runs through Carlisle’s narration of her education, James’s pithy observations about his long life in dance, and his efforts to shape Carlisle’s cultural education when she is a young girl.

As a child, Carlisle grows up with divorced parents, both veterans of the ballet world who open the possibility of a career in ballet as well. She lives in Ohio with her mother Isabel, a caring but somewhat passive parent. Carlisle’s periodic trips to New York to visit her father and James are where her visions of dance come to life. James is utterly devoted to Carlisle’s father, even as he carries a permanent air of melancholy and loss. He recounts his upbringing to Carlisle; it was full of culture but lonely. “He used to watch men make nets at the harbor,” she recalls him telling her. “The feel of cobblestones under bicycle wheels. The serenity and joy of ballet class. The power.”

When Carlisle is with James in New York, he tells her that “every block in the Village has something to say for itself.” He loves to drop names and morsels of cultural knowledge: “James Baldwin lived here. Jackson Pollock. On the six blocks of Bank Street alone: John Lennon and Yoko Ono, John Cheever, Merce Cunningham and John Cage, Patricia Highsmith, Will Cather. A famous acting studio run by Uta Hagen and Herbert Berghof.” Carlisle does her best to keep up: “I say, ‘Oh wow,’ even when I don’t know the names James is saying.”

They’re Going to Love You opens with “a shocking call” from James to Carlisle telling her that her father is dying. The mystery threading through the novel is how and why Carlisle has become estranged from these two men, particularly in light of how close the three were in her early years. As Carlisle prepares for the trip to her father’s deathbed, Carlisle narrates in the present while traveling through her younger life to reach the solution to the mystery.

Howrey brings an artist’s discipline to language. Her prose is lyrical, smooth, and thoroughly enjoyable. She is understated without being withholding. In one especially illuminating passage, James discusses his Harvard education with Carlisle and reflects on the nature of talent. He had come to college planning on a career as concert pianist and found out soon enough that he would not make it. “One can only become as good a musician as one is meant to be.

It’s the same with dance. For every artist, there’s a ceiling. As a teacher, your role is to make the very best of what is there. That’s why I don’t push my students. I explain. I say, ‘Here is what it wants to be, here is what it should be.’ They make of it what they can, or not. But one is always hoping. For that one student who transforms. Who takes your words and becomes better than nature intended.

Carlisle’s path into choreography is anything but smooth. As a teenager she is “big,” meaning tall, and she struggles with focus and discipline. She studies for a summer at the famed School of the American Ballet, at the end of which she is told she cannot stay for the full-year program. Carlisle suspects that “they’re concerned about my height, about my strength.” She’s humiliated. “They think I’m weak,” she thinks. “Huge and weak. I am these things. I’ve not pushed myself, proved myself. I’ve been living in a fantasy land. I’ve always known: if I’m going to be this tall, I need to be exceptional.” Whether this evaluation of herself is accurate doesn’t matter. Carlisle’s is a realistic and recognizable reaction to rejection, especially in the mind of a young girl—the turning against oneself, the all-consuming self-deprecation, and not just of one’s physical attributes but of one’s own mind.

Carlisle is loath to admit her failure to James and her father. “There’s a jagged rock in my sternum,” she thinks, defeated. “Maybe nothing is ever going to work out.” Her father senses something amiss and offers wisdom: “You’re a smart girl, you’ve got brains. And if you want to keep dancing you could take some modern dance classes, expand our technique. There are lots of different ways to work in the dance world. I should know.” James adds that ballet is “a chancy career at best.” Carlisle knows that “he means it kindly.”

To anyone who has been near ballet, or, for that matter, a career that requires as exacting a training, the subtext here is one of failure. Carlisle’s elders are gently pushing her away from her dream, acknowledging the sober realities of the profession. Underneath this exchange is also Carlisle’s propensity to skirt the whole truth, to conceal her emotional life in order to manage her anxiety. She has the trappings of an enriching upbringing, but she protects herself from the adults in her life by guarding her privacy. Communications with her father and James, and with her mother, are thus always fraught, creating the tension that helps drive the novel forward.

Eventually the reason for the rift between Carlisle and her father and James becomes clear, and with it, the reader’s understanding that Carlisle’s life may never have quite been her own. Her caution and privacy, her declining to openly rebel against her elders, may have actually worked against her. Her silence and efforts to live between the lines imbues the title to the novel with delicious irony.

But that part of the plot is less important than tracking the arc of Carlisle’s life, set in this rarified dance world, with plenty of professional and intellectual guidance but inadequate emotional support. Howrey is a master of unveiling the hidden emotional lives of her characters with grace and subtlety. The opening line of They’re Going to Love You says it best, inviting readers to travel alongside Carlisle on her journey: “Feel what I feel.”