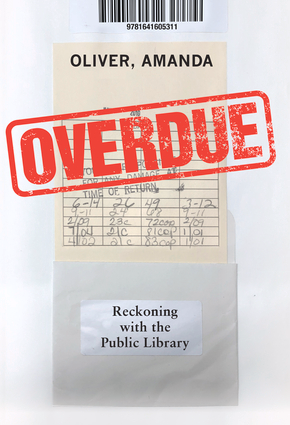

Growing up, the library was not just Amanda Oliver’s favorite place but also her “first beloved destination, first embodied center… it was absolutely sacred.” However, soon after Oliver began her career as a librarian at a Title I school and then in the D.C. public library system, she witnessed how systemic racism, income inequality, the widespread shortage of affordable housing, the opioid crisis and lack of mental health care impacted America’s most vulnerable library patrons, placing the burden on library staff working in high poverty environments to serve as mediators and mental health crisis support personnel.

The constant stress, verbal and sometimes physical abuse took its toll on Oliver’s mental and physical health, causing her to abandon the job she loved and write Overdue: Reckoning with the Public Library, a heart-wrenching polemic challenging the romanticized ideal of being a librarian.

Like Oliver, I am a former public school librarian who left my once beloved vocation after a trauma—I lost the use of my arms for nearly two years due to repetitive motion injuries which necessitated surgery after being ordered to pack a school library on my own. Around the time I resigned, I encountered Oliver’s advocacy for librarians in an essay. Her words made me realize we saw the same disparities, that I was not alone. Oliver and I recently met over Zoom, where we immediately connected over the mutual challenges we faced in the library, from retrofitting outdated collections featuring predominately white authors, to serving the needs of our diverse clientele on a limited budget, to being gaslit by administrators when we raised valid criticisms about how systemic racism and structural issues were impacting our ability to meet the needs of our patrons, to recognizing how working with limited resources in high poverty environments impacted our physical and mental health.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: In the opening chapters you discuss the mythology surrounding libraries: “It can be uncomfortable to think of libraries as social institutions that plainly tell the many layered stories of racism, classism, and deep-rooted neglect of marginalized and vulnerable populations in our community and across our nation…but to continue to laud libraries and librarians as ever-present equalizers and providers of some version of magic …prevents them from making meaningful changes and progress.”

Can you elaborate on how romanticizing libraries and ignoring systemic issues prevents libraries from making meaningful changes and progress?

Amanda Oliver: I completely understand the mythology and romanticization of libraries. It is obvious, and deserved, why they are so beloved. But when we idealize an institution to the point where we can’t or don’t or won’t look at its faults, both publicly and socially and also within the infrastructures of the institution, that’s a profound problem.

What’s particularly perplexing to me is the almost universally held view in America that libraries are somehow separate, or above, or outside of the many systemic issues impacting our entire country, when in fact our libraries embody them. I think more and more folks, especially in seeing the ways that libraries and librarians worked during the pandemic, started to understand the sheer magnitude of how much community support work was and is happening within libraries. And, again, this was held up as another shining example of the importance of libraries in America. But there’s a few missing pieces to that equation: the why this is the case—why libraries and library workers are tasked with so much and how this is indicative of pervasive inequities in this country—and also the weight of that responsibility being carried out by living, breathing people who are often not trained, capable, or sometimes even willing to do that work.

We so often look at libraries as beloved institutions without fully recognizing that they are not just physical buildings, or symbols of some best version of America…they are run by human beings who are often overworked and burned out from the insurmountable amount, and nature, of work they are being asked to do.

We can’t make progress or change to something if we don’t recognize there is a problem to begin with. And when we do the opposite—when we uplift an institution to the point of calling it things like “the last bastion of democracy” or “the last great equalizer,” as we so often do with libraries—it stops us from looking at them critically. Which, as with anything or anyone we treat this way, stops us from being able to make change or progress. If we don’t see a problem, we certainly can’t begin to see solutions.

DS: You worked as a librarian in DC, which has the largest gap in racial income inequality in this country, at a time when, due to technological shifts from 1980 to 2010, we have seen the demarcation between the social classes grow more extreme. How did working as a librarian in DC help inform your understanding of how class and caste operates in this country, particularly in regard to institutions like the library?

AO: I moved to D.C. right after graduating from my Master’s in Library Science program in 2011 and started working as a school librarian at a Title I elementary school a little over a mile from the White House. The students at that school were predominantly Black, Hispanic, and Mandarin Chinese and many of them lived in low-income housing right near the school. I learned very quickly that many of them were living in one or two-bedroom apartments with 10, 12, 14 other people. They’d come to school exhausted and tell me things like they’d been kept up all night by rats crawling on them. So many of my students lived in ways that I could not begin to really understand and then they still had to show up at school to learn and to take the same standardized tests as everyone else in the district. It became wildly clear to me very quickly how profoundly impactful class was within the K-12 school system, despite all of the reform work people like Michelle Rhea had been rolling out. When I eventually transitioned from school libraries to public I can remember thinking that so many of my adult patrons reminded me of my students and it felt like seeing the impacts of class inequality all grown up.

As far as how all of this plays out in libraries, there is a deep history of segregation in libraries by social class.

DS: You explore the history of the Library Company of Philadelphia, America’s earliest library. How did it shape how public libraries operated?

AO: The earliest free public library in America is generally accepted to be the Library Company of Philadelphia, founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1731. Franklin formed the Junto Club, which was a group of white, middle-class Philadelphia men who met for weekly meetings to improve their lives, their positions in their communities, and the societies they lived in. They regularly needed to look up information during their meetings and so they pooled their personal books into something of a collection, but eventually they wanted their books back in their homes. Franklin proposed a subscription library, 50 of them agreed to it, and the Library Company of Philadelphia—and the earliest version of the public library in America—was officially born.

When we idealize an institution to the point where we can’t or don’t or won’t look at its faults, that’s a profound problem.

All people of color were barred from accessing the Library Company. When Franklin and his peers founded the Library Company, teaching an enslaved person how to read was still illegal and punishable by death. Indigenous Americans were also forbidden access, though many had already been forcibly displaced and relocated from Pennsylvania to Midwestern territories by then. White indentured servitude was also common in colonial Philadelphia, and people in these groups—mostly women who were cultural and racial minorities, as well as the poor—were regarded as inferior to affluent white men and barred from accessing materials from most early libraries. Literacy was also a limiting factor, as education was reserved for middle- and upper-class White people. Even as access to education became more accessible to lower classes, and more of a public matter of concern, many students had to resign from school early to help work to support their parents and siblings in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Essentially, the very first version of a public library was created by and for middle- and upper-class white men, and this has permeated libraries for centuries.

DS: Can you discuss how libraries historically upheld white supremacy and segregation?

AO: Like I said earlier, our public libraries embody the history of our country, and this of course includes libraries and librarians upholding segregation, white supremacy, and xenophobia. In the early 1900s, when more than fifteen million immigrants were arriving to the United States, libraries and librarians distributed Americanization Registration Cards that required a signature agreeing to things like the use of a common language, the elimination of disorder and unrest, and “the maintenance of an American standard of living through the proper use of American foods, care of children and new world homes.” Librarians and libraries all over the country aided in the eradication of the culture, language, and customs of immigrants. Knowing that Black citizens fared even worse than them, the majority of immigrants chose to embrace whiteness and demonstrate their cultural and biological “fitness” to be white citizens, which further perpetuated and upheld white supremacy and segregation.

There is a deep, deep and lengthy history of discrimination and segregation against Black people in public libraries. It’s worth mentioning some of the brilliant Black librarians like Rev. Thomas Fountain Blue, Clara Stanton Jones, Virginia Lacy Jones, E.J. Josey, and Albert P. Marshall, who fought throughout their careers to desegregate libraries. We so often hear about Andrew Carnegie and Benjamin Franklin when we talk about the early history of libraries in America, but these folks were really leading the way and making change and uplifting libraries as truly public and accessible institutions.

By the 1950s and ’60s there were often still inferior and limited library services to Black people, but beyond that, Black patrons were often subjected to experiences in libraries that were humiliating. And librarians were often at the helm of this humiliation, refusing to give Black people library cards or to provide help for them at the circulation desk and supporting, or being complicit, when white patrons harassed them. These stories are often missing from the profession’s collective history.

DS: Since you left the library in 2018, the culture wars have grown more extreme. What do you think of the challenges faced by librarians now regarding censorship? How does refusing to reckon with our country’s history cause us to replicate the same patterns?

The very first version of a public library was created by and for middle- and upper-class white men, and this has permeated libraries for centuries.

AO: 2022 is on track to see the highest number of book challenges in public libraries in decades. That mirrors what’s happening in our culture at every level and I think everything is in the same vein—when we don’t acknowledge and work from and with a robust, nuanced, and complete truth about our histories, that includes failures and weaknesses and human and institutional errors and patterns, we’re doomed to repeat them.

DS: What kind of response did you receive from librarians when your book came out?

AO: It has been mixed. What I have been told more directly by librarians, usually in emails or at book events or in private messages, is that the book was reflective of, and validating to, their experiences in library work. Those communications have meant very much to me. I ultimately feel like I wrote a book that I wish I could have read when I was doing my Master’s in Library Science. For those librarians who have had dissimilar experiences to mine, they often express gratitude for the book’s contribution to a larger conversation.

What I have been told more indirectly, through online reviews and tweets, is that I was not a librarian long enough to have written the book. That came through loud and clear and was something I had been expecting, but still found disheartening. I certainly spent enough time in libraries and library work to understand on a much deeper level what is happening in our public libraries than, say, someone like Susan Orlean. And I was truly only able to write Overdue because I left library work. There was no way, mentally, emotionally, and, most specifically, legally, that I could have written it while working as a librarian.

So, I wrote the book I needed, and that I felt many others needed, about libraries. And it’s taken a great deal of time, space, and therapy, ha, to accept that I did not need to remain in the job longer to be able to write a “valid” account of my experiences. And certainly the many years of research and interviews that went into writing it are present. The book goes well beyond my personal experiences. Ultimately what I wanted to do was contribute to a more nuanced conversation around libraries and library work and I believe I was successful in that. I genuinely look forward to reading others’ work around their own experiences.

.jpg)

![[VIDEO] ‘Roswell New Mexico’ Season 4 Trailer: The CW Reboot Cancelled [VIDEO] ‘Roswell New Mexico’ Season 4 Trailer: The CW Reboot Cancelled](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/roswell-new-mexico-final-season.jpg?w=620)