“All academia is dark academia.” I said it without thinking, a knee-jerk reaction to a literary label that had been assigned to me but always felt ill-fitting. Until that moment—discussing my first novel, If We Were Villains, with the Folger Shakespeare Library book club—I hadn’t really understood why. It was the “dark” modifier I disliked. Not because what I’d written wasn’t dark, but because darkness is so intrinsic to academic life that it struck me as unforgivably redundant.

I hadn’t meant it as a joke, but the then-director of the library laughed, and so did everyone else. I’ve since repeated this line in a variety of settings, and it gets a big laugh every time. I’ve been listening to people laugh at it long enough that I can’t help wondering—what exactly is so funny?

When I was writing Villains in 2014, “dark academia” did not exist. Books have been written about university life as long as we’ve had universities, but until recently we just called them “campus novels.” The first one I read was John Knowles’s A Separate Peace, assigned in my sixth-grade English class. It disturbed and upset me, consumed me like an addiction, and after reading it half a dozen times, I went looking for a fix from other authors. Between then and the writing of Villains a decade later, I devoured every campus novel I could get my hands on. Unsurprising, in retrospect. Obvious, even—the way that word “dark” feels too obvious, like we’re all saying the quiet part out loud. I was a weird, friendless kid whose only natural aptitude in life was language. Words worked in my brain in a way nothing else did; the only place I didn’t feel out of my element was between the pages of a book or in an English class. A book that held classrooms between its pages offered the best of both worlds. Everywhere else I was walking on glass.

My early education was steeped in dogma and damnation. At my Catholic school, the line between moral and general instruction was thin; any minor misbehavior could be twisted into a violation of some commandment or sacrament. Coming to school with my shirt untucked was just one of a million ways I discovered to “dishonor my mother and father,” for instance. Such infractions were dutifully tallied and punished. Public humiliation was a popular option; when you’re twelve years old and simply existing is humiliation enough, having your sins itemized and excoriated by an authority figure before God and all your classmates is an exquisite form of torture.

Oblivious then to all the ways I really am “wrong” by Catholic standards (a queer woman with no interest in being a wife, mother, or nun), I hadn’t learned to wear my wrongness well. I only learned that God hated me and I was going to hell because I couldn’t keep my shirt tucked in or get my homework done. This pervasive culture of shaming followed me home and kept me up all night, crying and praying and begging Someone Upstairs to tell me why I just couldn’t be good. No matter how hard I tried not to do anything wrong, wrongness oozed out of my pores. By the time I learned that there’s a word for this manifestation of OCD—scrupulosity—I was four years deep in a doctoral degree and my crippling fear of not being good had lost its religion and transformed into a crippling fear of not being good enough.

Academia and Catholicism look a lot alike if you squint.

Even in a secular institution, academia and Catholicism look a lot alike if you squint. My early indoctrination and difficult exodus from that religious community created a natural pipeline to the academy. I traded one higher power for another that seemed a little more friendly to the “wrong” kind of person I was but operated in much the same way.

Catholicism runs on self-sacrifice. It demands you punish yourself in an extravagant, Christlike style. Suffering is good. Deprivation is godly. Pain is the way to salvation. Academia, especially after undergrad, follows the same schematic. The fetishistic self-flagellation of Catholicism sounds a lot like the virtue-signaling characteristic of campus communities: end-game capitalism has equated our worth with our willingness to destroy ourselves for productivity, and in higher education this compulsion takes on the distinctly religious bent of self-righteous self-destruction for the cause. The demonstration of scholastic rigor has become so rigorous indeed that we expect graduate students to write 400-page monographs that make novel interventions in their field at the same time that they’re teaching undergraduates and supporting the research of more senior scholars, usually while working other jobs to supplement their stipend, with no guarantee that anyone outside their committee will even read their work when it’s complete and even longer odds that there will be a job for them when they graduate.

Academia demands—and rewards—uncompromising devotion and unquestioning acceptance.

Only the fervor of a true believer will sustain you through five to seven years of that. Like the church, academia demands—and rewards—uncompromising devotion and unquestioning acceptance. In church and on campus, you don’t contest your higher power. God brooks no challenges to his wisdom, and academic administrations project the same infallibility, even when their practices are both illogical and morally bankrupt. At the university where I completed my PhD, eight of the ten highest earners were athletic coaches, each making more than 40 graduate students combined. When I was the president of the Graduate English Organization, it was my responsibility to represent student concerns to the administration during the worst year of COVID-19. Coaches who weren’t even coaching would continue earning $800,000 annually, but whether we would get to keep our health insurance during a global health crisis if we weren’t teaching in person was up for debate. My duty to my peers put me in the impossible position of having to make myself a nuisance to the superiors who held my professional future in their hands. More than once I was shouted down in departmental meetings by a male faculty member who was not only ostensibly in charge of student welfare but my direct supervisor in one of the assistantships I took on to make ends meet. Later, another faculty member acknowledged that his behavior was wildly inappropriate, but it was easier to wait for his term to expire than to take any disciplinary action. I was, after all, just a graduate student, but I felt more like a Catholic school student still: publicly humiliated and threatened with excommunication for my failure to toe the line. There is no inheritance for the meek in academia. The people at the bottom have no leverage by design, because if they did, they’d flip the tables over in no time.

So why does anybody submit to this dehumanization here in the 21st century? Like the long, twisted history of Catholicism, it’s a tragic sort of love story.

While the academy undoubtedly fosters competition and tends to attract “high achievers,” scholastic achievement is never achievement for its own sake. Nobody pursues a terminal degree without a passionate love of their subject. I was no exception; my first encounter with Shakespeare in elementary school had an epiphanic quality. He spoke to me the way I imagined God speaking to my more worthy classmates. There was something in the words themselves—what I would later recognize as a cultural and linguistic kinship with the King James Bible which had been the cornerstone of my theological education—intoxicating as a drug. By the time I was 22 and writing Villains, I knew a career as an actor was not in the cards for me, so I sold my soul to the academy because it was the only other way I knew to do what I loved for the rest of my life. But the cruelest truth of the academy is how hard it is to keep loving something which is slowly killing you. Sometimes literally.

In the last six months before my dissertation defense, my normal scholastic obsessions metastasized into something black and monstrous that devoured every waking moment and still was not satisfied. I went days without sleep, sometimes a week or longer. Sleep debt became sleep deprivation psychosis. I spent the winter of 2023 sliding in and out of a dissociative state where I ceased to exist as a person and became a purely intellectual process, inseparable from the document itself. I turned off the clock on my computer so I couldn’t see how time was passing, couldn’t feel the minutes slipping through my fingers. This trick was devastatingly effective; time moves differently at night, when there are no external indicators that the world is turning. My tunnel vision grew so intense that I might sit hunched over my desk for ten or twelve hours straight, and only realize how long I’d been there when the sun came up again. Without this time warp I never would have finished my dissertation by deadline, but it was a diabolical bargain.

The cruelest truth of the academy is how hard it is to keep loving something which is slowly killing you.

Sleep deprivation, like public shaming, has been used as a form of torture across time and cultures; without rest our bodies and our brains break down in tandem. We lose our grip on what’s real, including the consequences. When my defense was in sight, nothing else mattered. I endured or ignored the nerve damage, the vomiting fits, the headaches and the heart palpitations, the frequent fainting spells, all the while telling myself that once it was over, then I would be well. Instead, I made myself so sick that my heart stopped and I was dead on the table one week before my defense.

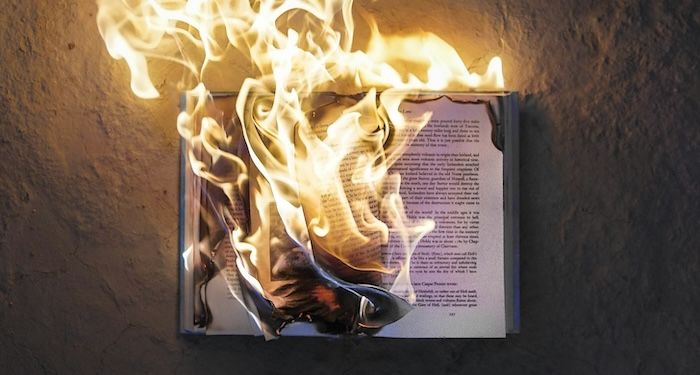

My case is an extreme one, to be sure, and I’m as much to blame as anyone for getting myself in so deep. But the aftershocks will live with me a long time; they live in my blood and my heart and my bones—anemia, dysautonomia, osteopenia, CPTSD. The dark side of academia is dark indeed.

Maybe this is partly why the term “dark academia” doesn’t sit well with me. I envy the writers and readers who can still romanticize academia, darkness and all. I cannot read these novels anymore, still in recovery from my torturous affair with the academy. When my own readers ask me about my scholastic background, I warn them as best I can that graduate school doesn’t look anything like what they see in these books, even mine—penned when I was 22 and full of the same innocent intensity. I tell them instead it will eat them alive and spit out the bones and pick its teeth and lick its lips and reach for the next fresh batch of applications with a delicate belch. Nine times out of ten I can tell they don’t believe me, aren’t really listening, don’t want to hear that their lofty ideals are just that and have no purchase in the real world. The false promise of a life of the mind is as seductive now as it was to Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, who sold his soul to the devil for knowledge.

But the darkest part of academia is that none of this will change. There will always be another willing sacrifice. For a few years now I’ve lived with guilt like I’ve always done, worried now by how many readers might be getting the wrong idea about academia, pursuing graduate degrees for the wrong reasons. Even in my youthful first novel, I tried to take a critical view of the academy; I didn’t set out to glamorize the vicious competition or the chronic overwork or the rampant substance abuse embraced as a collective coping mechanism. The whole “moral” of the story, if there is one, is that this permissive disregard for human welfare is exactly what’s unforgivable in the academy, what ruins lives and drives its initiates to distraction. Perhaps I was too subtle; many readers—especially the ones who are youngest, who don’t yet have the critical reading skills to read between the lines because they haven’t yet done their time in higher education—miss the point completely. They’re swept up in the “aesthetic,” the “vibes,” the flatlays and outfits-of-the-day, the fantasy of belonging to an exclusive society of the intellectually anointed.

I wish more of these novels took a hard look at themselves, took a more critical view of the lifestyle they describe, presented a more realistic reflection of academic life which includes not only precocious undergraduates but the people who grade their papers and cook their meals and clean their dorms; which not only rhapsodizes about lifelong love affairs with literature but condemns the institutional practices that make that kind of work completely unsustainable. Where are the campus novels about students saddled with so much debt they’ll never climb out of it? Where are the campus novels about the alarming rates of depressive disorders and suicidal ideation among graduate students? Where are the campus novels about nineteen-year-olds dying in reckless hazing rituals? “Dark academia” isn’t just a fiction: it’s a fantasy, and a dangerous one.

How, then, to mitigate the damage? There is an opportunity here to use the popularity of these books to encourage thoughtful conversation and critique about the dark parts of higher ed which aren’t so sexy, aren’t so tempting, don’t look so good on Instagram. It puts authors in a tough spot: to keep selling books, we have to embrace the trend, and if we resist, our publishers will do it on our behalf. Publishing, like academia, broadcasts its love of arts and letters, but still answers to the higher power of the bottom line. Over the last few years, that ever-present guilt in me has grown in tandem with the popularity of this shelfmarker. Whenever I have the chance to speak directly to readers, I warn them away from making the same mistakes I did, the same mistakes the characters in my books do. I wrote my short story “Weekend at Bertie’s” and my first novella, Graveyard Shift, against the grain of the genre: the characters are suffering, struggling casualties of what we might call the academic-industrial complex; the darkness is ugly and unglamorous; the critiques of the academy and the genre itself are much more overt. It wasn’t until halfway through the writing of Graveyard Shift that I realized it should be shelved as horror. A fitting generic shift: for the last four years I, like Victor Frankenstein, have fought a losing battle against my own monstrous creation.

When I talk to readers now, I sound like a well-meaning DARE officer warning them away from drugs. It’s not like you see in the movies, kids. It won’t make you cool, make you happy, make you friends, but it might just make your life a living hell: take it from me, I speak from experience. Will this move the needle, solve the problem? No; so long as we let them, people will continue to swallow “dark academia” hook, line, and sinker. But we have a responsibility to do more than wring our hands and collect the royalties. Even writers of fiction must be truthtellers sometimes.

I’ll go first: I’m sorry for my part, however unwitting, in perpetuating the romantic misconceptions of academic life. For my penance I’ll spend the rest of my writing life trying to set the record straight, pushing my readers to embrace the real intellectual work of the academy, which is to read closely and critically, with a healthy separation of fact and fiction, romance and reality. I should have done it more, and done it sooner. Shame on me.