When I last interviewed 5 Under 35 honoree Alexandra Chang, we spoke about her debut novel, Days of Distraction . This was in February of 2020. Our conversation could not help but drift from the text to the impending apocalypse.

. This was in February of 2020. Our conversation could not help but drift from the text to the impending apocalypse.

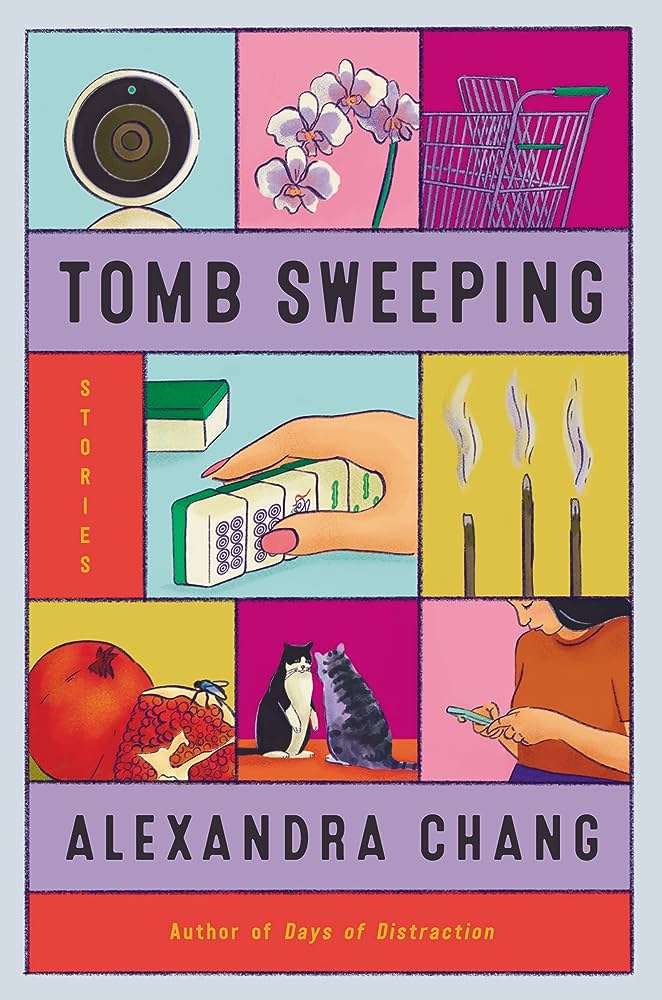

Chang’s short story collection, Tomb Sweeping, arrives at a slightly less cataclysmic time. This is to the benefit of readers, who will find a special voice they might have missed during the early lockdown days, a voice that Jason Mott—the National Book Award winner for Hell of a Book—describes aptly as “haunting and mesmerizing.”

Tomb Sweeping has a prevailing mood that is present in the best story collections, a sense of completeness. The stories were written over the course of nine years, and, individually, each reads with the effortlessness achieved through dedicated revision. Chang and I talked about the short story form, grocery store marketing strategies, and decisions made when revising.

Alexander Sammartino: How do you think about the way the stories in Tomb Sweeping come together?

Alexandra Chang: I tried organizing them a few different ways. I initially liked the idea of stringing them together chronologically, mostly so I could see how I’ve changed as a writer over the years, but then I didn’t like how they read in that order. I tried to organize them thematically, kind of clumping stories with similar concerns together (e.g. family, self, work, friendship, etc.)—that got repetitive. Eventually I landed on a more intuitive and mood-based organization, balancing between familiarity and change from story to story. I also had a couple contenders for the first story and a couple contenders for the last story. I like the idea of the beginning and end being bookends of the collection, then filling in the rest.

AS: You’ve worked on these stories for years, so I’m curious—which story changed the most through revision and how?

AC: “Cure for Life.” Overall, the story maintained its setting (a grocery store) and concerns (the relationship and power dynamic between this 24-year-old guy and a 14-year-old girl who work together). I initially wrote it in first person, from the teenage girl’s perspective, and the events of the story were pretty different. I just reread that initial draft for the first time in years and am missing her voice now. I’m seeing that she was less innocent and coming into her power in that first draft. But something about her character didn’t seem to be working at the time that I first wrote it, and I left it alone for a couple years until deciding to try writing it from the guy’s perspective, in close third. I was also just curious about him. Writing really is a series of choices. It reads like a totally different story now. I’m working on a novel that’s set in the same grocery store, so I’ll do something else with the girl’s voice.

AS: What drew you to the supermarket setting for “Cure for Life”?

AC: I worked in a big, gourmet grocery store through most of high school. The experience was formative for me and I’m still trying to figure it out through writing. (My next novel is set in the same store.) The space itself is really interesting—I mean, practically everyone in this country has spent time in a grocery store. They’re designed to seduce people into buying more stuff. There’s just so, so much excess—and so much marketing going into it—it’s very disorienting in an alluring way. I’ll never get over how many varieties of yogurts exist.

I’m also into reading and writing about work in general, and the store setting felt like fertile ground. There’s a clear class divide between the employees and the customers. The creepy corporate “family” culture was also very strong where I worked. But what I was drawn to most were the relationships and drama within the store.

AS: I’d love to hear about some of the absurd marketing stuff.

AC: The one I worked at really leaned into that homey, pseudo-European market feel, but at 20 times the size. They have these fancy signs hanging from the ceilings all over the store—there are employee stories and quotes; facts about all the good things the grocery store does (recycle, donate hundreds of thousands of pounds of food, use LED lights, etc.); maps of where the food travels from; mission statements; slogans. When I worked there more than a decade ago, there was also this huge scoreboard above the store entrance, listing the store and all of its nearby competitors, that marked for wins and losses based on grocery prices. I mean, it was clearly skewed in the store’s favor.

Other than that, there’s tons of product marketing and branding. So much sensory overload. I actually really dislike being inside grocery stores now. The weirdest stuff I experienced was more behind-the-scenes—“internal communications”—with employees, to get us to be acolytes of the store. There was one holiday party where cash fell from the sky.

AS: You mentioned that the story “Unknown by Unknown” follows a particular structural pattern. Can you talk more about that?

AC: It’s based on kishōtenketsu, which is a Japanese term for a traditional four-part structure that’s common in classical (and contemporary) East Asian literature and storytelling. I believe the form originated from a structure of early Chinese poems. Some people call it a “plotless” story structure, but I disagree. There’s plot, in the sense that there is cause and effect at some point, it’s just that there aren’t traditional Western elements of rising action, climax, and resolution. A lot of my stories lean more toward kishōtenketsu structure, but I made it explicit in this story by dividing it into four sections.

Those four parts are, traditionally:

1. Ki/Introduction: In “Unknown by Unknown,” I just set up the character and her voice, and establish that she’s going to housesit.

2. Sho/Development: Expanding on the introduction; the narrator lives out her housesitting days. There’s more on setting and her routine. Nothing changes here for characters.

3. Ten/Twist: This is probably the closest to a climax. Something unexpected happens and this changes the character’s world or situation. (I guess I won’t spoil the story here.)

4. Ketsu/Conclusion: I like the use of the word conclusion, rather than resolution. It typically isn’t a neat ending, and the character doesn’t necessarily triumph or grow in any way. It’s just what happens after the twist.

AS: The book closes with “Other People,” a story that has a narrator recounting a story someone else told her. Why did a frame feel right there?

AC: “Other People” is partly a story about the effect other people’s stories have on you, and the lives those stories have in the world, outside of the original teller. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about stories that have nothing to do with me (e.g. fiction), and I enjoy talking about those stories with people. The frame (and frame within the frame) felt like a way to make explicit this mode of engaging with stories. I think of the structure as a Russian doll, or maybe a game of telephone. You have the narrator telling the story to the reader, Jack telling the narrator the story, and Alice—who the core story is about—telling it to Jack. Each of them is adding their own interpretations and perspectives to the story, so it’s this very layered thing that has each characters’ imprint on it once it arrives at the reader. Or so I hope.

AS: What do you find most compelling about the short story form?

AC: The constraint of its size and how much can fit within it. Sure, short stories can range from flash to upwards of 7,000 words, but there’s a limit, and what writers can accomplish within that limit is so varied and really exciting.

The post Alexandra Chang Is Compelled by Constraint appeared first on The Millions.