I sold a book this past year, a memoir in essays that now I have to… actually sit down and write. So I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on my life, trying to craft some sort of cohesive account of who I am and how I came to be that way without taking shortcuts or embellishing too much. It is difficult. As a reader of novels, not to mention a frequent seeker of therapy, I know how tempting it is to impose a narrative arc onto the world in order to make sense of it. I know the Joan Didion merch is right: we do tell ourselves stories in order to live. But what happens to all of those stories I’ve told myself when I’m trying to write nonfiction?

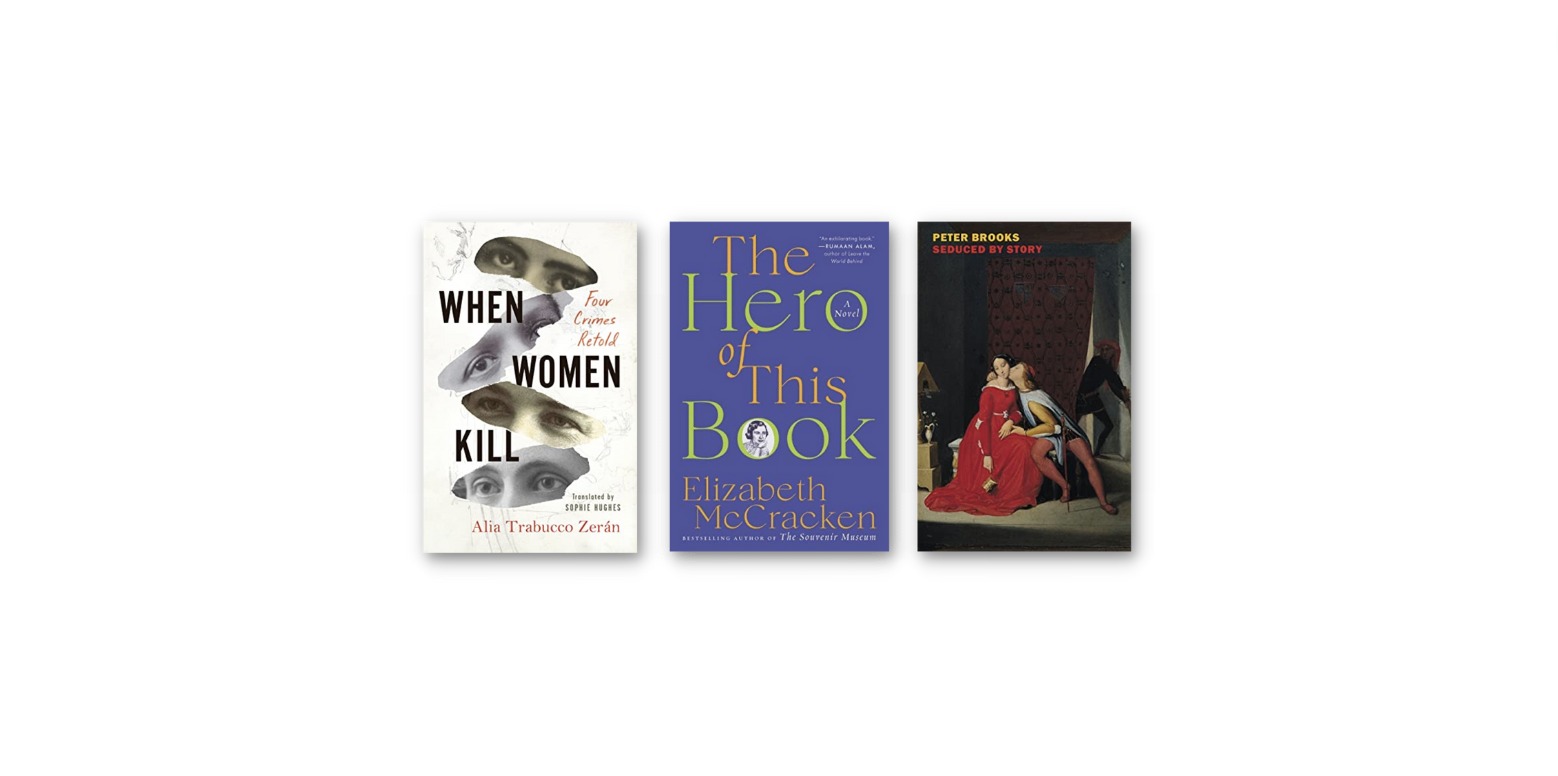

Then this summer I read Seduced by Story: The Use and Abuse of Narrative by Peter Brooks, a book that warns of the dangers of “the storification of reality.” There’s nothing better than a story when we seek it in literature, Brooks argues, but what works in great fiction (and he’s so good at showing us what works and doesn’t work and why) is so often inadequate when applied to real life. Telling a believable story, for example, often seems to matter more than presenting facts in a court case. And each time the Supreme Court decides a case, the justice writing the majority opinion has to tell a story about what the Constitution says, and how previous rulings affirm the narrative they’ve constructed. Brooks also gives less dire but equally annoying examples of how the advertising world has bought into the idea that each and every brand should have their own story too. Truly, who the fuck cares how the owners of your low-carb cereal brand met?

Then this summer I read Seduced by Story: The Use and Abuse of Narrative by Peter Brooks, a book that warns of the dangers of “the storification of reality.” There’s nothing better than a story when we seek it in literature, Brooks argues, but what works in great fiction (and he’s so good at showing us what works and doesn’t work and why) is so often inadequate when applied to real life. Telling a believable story, for example, often seems to matter more than presenting facts in a court case. And each time the Supreme Court decides a case, the justice writing the majority opinion has to tell a story about what the Constitution says, and how previous rulings affirm the narrative they’ve constructed. Brooks also gives less dire but equally annoying examples of how the advertising world has bought into the idea that each and every brand should have their own story too. Truly, who the fuck cares how the owners of your low-carb cereal brand met?

Once I began to notice it, I saw it everywhere. What isn’t storified these days, with cable news turning politics into 24-hour entertainment, and the latest true crime boom turning acts of violence into digestible 45-minute podcasts? And so the idea of narrative abuse began to color everything I read. I saw the Brooksian angle on the trauma plot in contemporary fiction: how the tragic circumstances of a character’s early life fully correlate to present behavior in a way that feels much too simple. Meanwhile, “reads like a novel” is high praise (I use it a lot!) for much of the nonfiction that I enjoy, but again, if every supposedly true story reads like a novel, then what happens to facts?

It turns out that the books to which I’m most drawn, in 2022 and just about every year, are the ones that resist the hero’s journey, the easy answers, the neat little bow tied at the end.

No nonfiction book was as pleasingly messy as Rachel Aviv’s Strangers To Ourselves. “Mental illnesses are often seen as chronic and intractable forces that take over our lives,” Aviv writes in her introduction. “But I wonder how much the stories we tell about them, especially in the beginning, can shape their course.” And so her exploration of mental illness through five case studies asks a lot of questions but resists definitive conclusions, foregoing the kind of satisfying ending that publishers love to offer at the end of just about every pop/psych book. Aviv resists, showing how there are no universal themes in treatment of mental health except that each and every individual case is different. Oh, and the American healthcare system sucks, of course.

No nonfiction book was as pleasingly messy as Rachel Aviv’s Strangers To Ourselves. “Mental illnesses are often seen as chronic and intractable forces that take over our lives,” Aviv writes in her introduction. “But I wonder how much the stories we tell about them, especially in the beginning, can shape their course.” And so her exploration of mental illness through five case studies asks a lot of questions but resists definitive conclusions, foregoing the kind of satisfying ending that publishers love to offer at the end of just about every pop/psych book. Aviv resists, showing how there are no universal themes in treatment of mental health except that each and every individual case is different. Oh, and the American healthcare system sucks, of course.

I was also entirely taken with When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold by Alia Trabucco Zerán and translated by Sophie Hughes. It’s a reconsideration of four women who committed homicides in Chile in the twentieth century and became notorious for having perpetrated such unladylike crimes. Zerán breaks down the mythologies about each of the women and seeks facts in court records and other historical documents. Often information is scarce, and that’s okay. She allows these stories to remain incomplete, the women’s motives implied (yes, systemic oppression of women was unsurprisingly a factor) but not entirely spelled out.

I was also entirely taken with When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold by Alia Trabucco Zerán and translated by Sophie Hughes. It’s a reconsideration of four women who committed homicides in Chile in the twentieth century and became notorious for having perpetrated such unladylike crimes. Zerán breaks down the mythologies about each of the women and seeks facts in court records and other historical documents. Often information is scarce, and that’s okay. She allows these stories to remain incomplete, the women’s motives implied (yes, systemic oppression of women was unsurprisingly a factor) but not entirely spelled out.

My favorite fiction of the year was Namwali Serpell’s The Furrows, a novel that shows how traditional narratives fail in times of grief. The stages of grieving don’t run in a five-step straight line; instead it’s a never ending circular cycle that can pull you back under at any time out of nowhere. “I don’t want to tell you how it happened,” the narrator of the first part of the story tells the reader repeatedly. “I want to tell you how it felt.” All you need to know is that when the narrator was a kid, her little brother died on her watch; the particular circumstances of his death don’t matter. There’s freedom in not having to worry about the details as a reader, just allowing the feelings to wash over you.

My favorite fiction of the year was Namwali Serpell’s The Furrows, a novel that shows how traditional narratives fail in times of grief. The stages of grieving don’t run in a five-step straight line; instead it’s a never ending circular cycle that can pull you back under at any time out of nowhere. “I don’t want to tell you how it happened,” the narrator of the first part of the story tells the reader repeatedly. “I want to tell you how it felt.” All you need to know is that when the narrator was a kid, her little brother died on her watch; the particular circumstances of his death don’t matter. There’s freedom in not having to worry about the details as a reader, just allowing the feelings to wash over you.

And now it’s time for me to get googly-eyed about Elizabeth McCracken, a thing that happens to me quite often. The Hero of This Book is a perfect example of when the use of narrative is helpful, necessary, even. “If you want to write a memoir without writing a memoir,” says the narrator of the book who may or may not be a fictional representation of the author herself, “go ahead and call it something else. Let other people argue about it.” In order to write about the death of her mother who was big-hearted but very private, the author calls her remembrances of her mother a novel, and with one swift edit foresakes the parameters of nonfiction and allows herself to write the book she wants to. I underlined just about every sentence, enjoying how much fun (yes, even in a book about grief) the author clearly has in blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction.

And now it’s time for me to get googly-eyed about Elizabeth McCracken, a thing that happens to me quite often. The Hero of This Book is a perfect example of when the use of narrative is helpful, necessary, even. “If you want to write a memoir without writing a memoir,” says the narrator of the book who may or may not be a fictional representation of the author herself, “go ahead and call it something else. Let other people argue about it.” In order to write about the death of her mother who was big-hearted but very private, the author calls her remembrances of her mother a novel, and with one swift edit foresakes the parameters of nonfiction and allows herself to write the book she wants to. I underlined just about every sentence, enjoying how much fun (yes, even in a book about grief) the author clearly has in blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction.

I’m still writing (or trying to write) my essays, and I’m not planning on turning them into a roman a clef just yet. But I’m grateful for the books I’ve read this year that challenged my assumptions about what a story can and can’t do. Now I just have to learn how to put down other books and actually feel confident to work on my own. It’s a process.