This year marked a huge and welcome shift in my reading habits: I started reading fiction again, for the first time in thirteen years. I know, I know! I didn’t mean to stop for so long.

I kept meaning to get back to fiction, but as I was writing a memoir and then an essay collection, while editing essays and memoir and teaching memoir… the pile of nonfiction books that I urgently had to read—either as research for my own writing, or in preparation for a class or panel, or just to stay up on what was new in the genre—was constantly replenished and spilling over like Strega Nona’s pasta pot. As I scrambled to keep up, somehow more than a decade passed.

After so long away, it felt like I was starting from scratch—staring down all of fiction, frozen in uncertainty over where to start: With the years’ worth of contemporary fiction that I missed while I single-mindedly focused on nonfiction? With the classics that had been languishing on my “to read” list since I was a precocious, bookish child? I knew the real answer was “just pick up a book,” but I still felt stuck at the question, “but which book?” This indecision prolonged the unintended break even longer.

Eventually, at the end of 2022, I did what I always do when I’m overwhelmed: I made a spreadsheet. At first, I thought I’d categorize books by subgenre or style, but realizing how quickly that would devolve into debates about when exactly certain movements started or the finer points of distinctions between similar styles, I decided to go by decade instead (with some larger spans of time pre-1900s). I started filling columns with all the titles on my shelves and mental lists that I always meant to read, then perused tons of lists I found online (of books by era, movement, original language, etc.), and eventually turned to Twitter (RIP) for further recommendations. I ended up with about 200 titles, soothingly organized and laid out in a grid. (I know spreadsheets are not soothing to everyone, but they are to me.)

For all of 2023, I’ve been working my way through my fiction spreadsheet by decade, slotting in a contemporary novel after every older one, so for example, a particularly good run was: To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927), There, There by Tommy Orange (2018), The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler (1939), The Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee (2016), The Setting Sun by Osamu Dazai (1947), Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff (2015), etc. Interspersing contemporary novels with older works keeps the bar raised for the new stuff, I think—variety in era and style means weighing contemporary novels not just against each other, but against Woolf and Chandler and Dazai (and Joyce and Bulgakov and Morrison) as well. And finding current authors that can hold their own in that company (as Chee, Orange, and Groff can), has been really thrilling.

For all of 2023, I’ve been working my way through my fiction spreadsheet by decade, slotting in a contemporary novel after every older one, so for example, a particularly good run was: To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf (1927), There, There by Tommy Orange (2018), The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler (1939), The Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee (2016), The Setting Sun by Osamu Dazai (1947), Fates and Furies by Lauren Groff (2015), etc. Interspersing contemporary novels with older works keeps the bar raised for the new stuff, I think—variety in era and style means weighing contemporary novels not just against each other, but against Woolf and Chandler and Dazai (and Joyce and Bulgakov and Morrison) as well. And finding current authors that can hold their own in that company (as Chee, Orange, and Groff can), has been really thrilling.

One of the first books I read in my Great Return to Fiction, and where the reading project really gained momentum, was Moby-Dick. I’d tried reading it twice before—once as a way-too-young kid (at my father’s urging) and again in my early 20s (still a way-too-young-kid). Both times I “didn’t get it” and set the book aside after a few chapters. But something clicked this time and I am now a full-fledged Melville convert. The haters don’t know what they’re talking about: Herman Melville was a genius, Moby-Dick is brilliant and hilarious, and the supposedly-boring “whale chapters” are the best parts.

One of the first books I read in my Great Return to Fiction, and where the reading project really gained momentum, was Moby-Dick. I’d tried reading it twice before—once as a way-too-young kid (at my father’s urging) and again in my early 20s (still a way-too-young-kid). Both times I “didn’t get it” and set the book aside after a few chapters. But something clicked this time and I am now a full-fledged Melville convert. The haters don’t know what they’re talking about: Herman Melville was a genius, Moby-Dick is brilliant and hilarious, and the supposedly-boring “whale chapters” are the best parts.

In between my fiction binging, I read some nonfiction this year, too. I especially enjoyed reading Claire Dederer’s Monsters in a two-person book club with my husband, Soomin. We’ve been together for ten years, and for about that long we’ve had an ongoing conversation (that sometimes veers into debate) about the exact question at the heart of Dederer’s book: Can we still enjoy art made my monsters? So as soon as I heard about this book, I preordered two copies, and when they arrived in April, Soomin and I read a couple of chapters a week and discussed them on Sundays. It didn’t settle the question for us, but it added interesting depth and texture to the way we talk about it. This was really fun, I highly recommend making a book club with your spouse.

In between my fiction binging, I read some nonfiction this year, too. I especially enjoyed reading Claire Dederer’s Monsters in a two-person book club with my husband, Soomin. We’ve been together for ten years, and for about that long we’ve had an ongoing conversation (that sometimes veers into debate) about the exact question at the heart of Dederer’s book: Can we still enjoy art made my monsters? So as soon as I heard about this book, I preordered two copies, and when they arrived in April, Soomin and I read a couple of chapters a week and discussed them on Sundays. It didn’t settle the question for us, but it added interesting depth and texture to the way we talk about it. This was really fun, I highly recommend making a book club with your spouse.

During the first few months of this year, I was also finishing revisions on my essay collection, First Love: Essays on Friendship, which comes out in May. I’d written the essays out of order, following my interests and whims, which was all well and good until it was time to put them together and revise them not as fifteen separate pieces but as one cohesive whole. As I faced this task, I revisited a few beloved collections for inspiration and guidance: I reread to Melissa Febos’s Girlhood, which became one of my all-time favorites before I was even finished reading it the first time. I will forever be in awe of her ability to synthesize big, complicated concepts and tons of research without ever losing the intimate tone that makes her essays feel like she’s telling you, personally, about her inner life. I returned to CJ Hauser’s The Crane Wife, because their essays have such impressive variety in subject matter and structure, but feel undeniably held together by the centripetal force of Hauser’s voice. I reread to Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel because I remembered being so impressed the first time with how he handled the repetition of central events in his life, so it felt like each essay peeled back new layers rather than simply circling back to something we’d seen before. (I was just as impressed by this on reread.) And Elissa Washuta’s White Magic, for a dose of permission to get weird with form and to let my essays sound like me rather than like some pre-established Literary Voice.

During the first few months of this year, I was also finishing revisions on my essay collection, First Love: Essays on Friendship, which comes out in May. I’d written the essays out of order, following my interests and whims, which was all well and good until it was time to put them together and revise them not as fifteen separate pieces but as one cohesive whole. As I faced this task, I revisited a few beloved collections for inspiration and guidance: I reread to Melissa Febos’s Girlhood, which became one of my all-time favorites before I was even finished reading it the first time. I will forever be in awe of her ability to synthesize big, complicated concepts and tons of research without ever losing the intimate tone that makes her essays feel like she’s telling you, personally, about her inner life. I returned to CJ Hauser’s The Crane Wife, because their essays have such impressive variety in subject matter and structure, but feel undeniably held together by the centripetal force of Hauser’s voice. I reread to Alexander Chee’s How to Write an Autobiographical Novel because I remembered being so impressed the first time with how he handled the repetition of central events in his life, so it felt like each essay peeled back new layers rather than simply circling back to something we’d seen before. (I was just as impressed by this on reread.) And Elissa Washuta’s White Magic, for a dose of permission to get weird with form and to let my essays sound like me rather than like some pre-established Literary Voice.

Another wholly separate category of my reading this year is the history audiobooks I listen to at night (which, yes, counts as reading). For years, I listened to old episodes of Law & Order on my iPad to fall asleep (which does not count as reading), but I finally made the switch in the name of better sleep—I used to always wake up for a few moments during the loud climactic scene that inevitably comes about 30 minutes into an episode of Law & Order, but this doesn’t happen with audiobooks. Long, dense narrative histories strike the perfect balance of being interesting enough to hold my attention and quiet the incessant internal monologue that would keep my up all night without some external stimulus to latch onto, but dry enough that I can easily drift off after half an hour or so. I’ve been on a streak of books about influential families lately, and a few favorites have been The Borgias by Paul Strathern, The Brothers York by Thomas Penn, and The Romanovs by Simon Sebag Montefiore.

Another wholly separate category of my reading this year is the history audiobooks I listen to at night (which, yes, counts as reading). For years, I listened to old episodes of Law & Order on my iPad to fall asleep (which does not count as reading), but I finally made the switch in the name of better sleep—I used to always wake up for a few moments during the loud climactic scene that inevitably comes about 30 minutes into an episode of Law & Order, but this doesn’t happen with audiobooks. Long, dense narrative histories strike the perfect balance of being interesting enough to hold my attention and quiet the incessant internal monologue that would keep my up all night without some external stimulus to latch onto, but dry enough that I can easily drift off after half an hour or so. I’ve been on a streak of books about influential families lately, and a few favorites have been The Borgias by Paul Strathern, The Brothers York by Thomas Penn, and The Romanovs by Simon Sebag Montefiore.

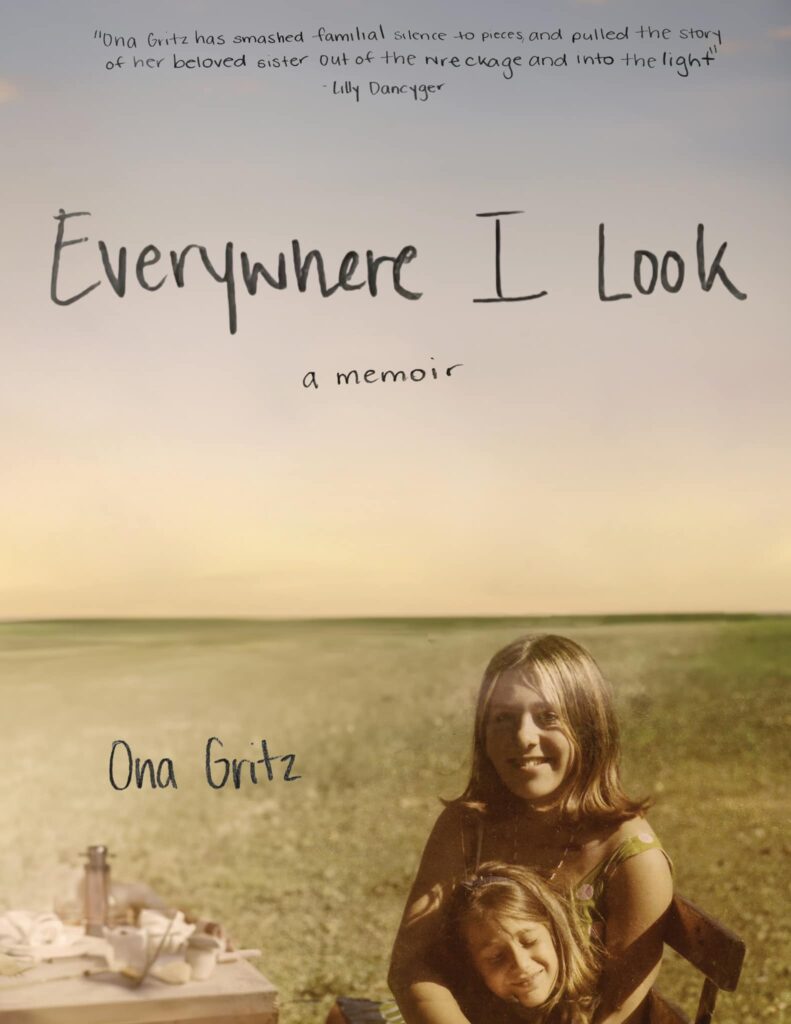

And lastly, I have to mention a few books that are coming out in 2024 that I’ve been lucky enough to read advance copies of: Nina St. Pierre’s Love is a Burning Thing, a masterpiece of a memoir about her mother’s undiagnosed mental illness and spirituality (and the often blurry line between the two); Ona Gritz’s Everywhere I Look, a memoir about her sister’s murder that pulls back a thick cloak of family secrets; and Leslie Jamison’s Splinters, the most intimate and beautiful work yet from one of the best nonfiction writers of our time.

And lastly, I have to mention a few books that are coming out in 2024 that I’ve been lucky enough to read advance copies of: Nina St. Pierre’s Love is a Burning Thing, a masterpiece of a memoir about her mother’s undiagnosed mental illness and spirituality (and the often blurry line between the two); Ona Gritz’s Everywhere I Look, a memoir about her sister’s murder that pulls back a thick cloak of family secrets; and Leslie Jamison’s Splinters, the most intimate and beautiful work yet from one of the best nonfiction writers of our time.

More from A Year in Reading 2023

A Year in Reading Archives: 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

![[Spoiler] Wins in Season 1 Finale – TVLine [Spoiler] Wins in Season 1 Finale – TVLine](https://washingtonweeklytimes.com/wp-content/themes/jnews/assets/img/jeg-empty.png)