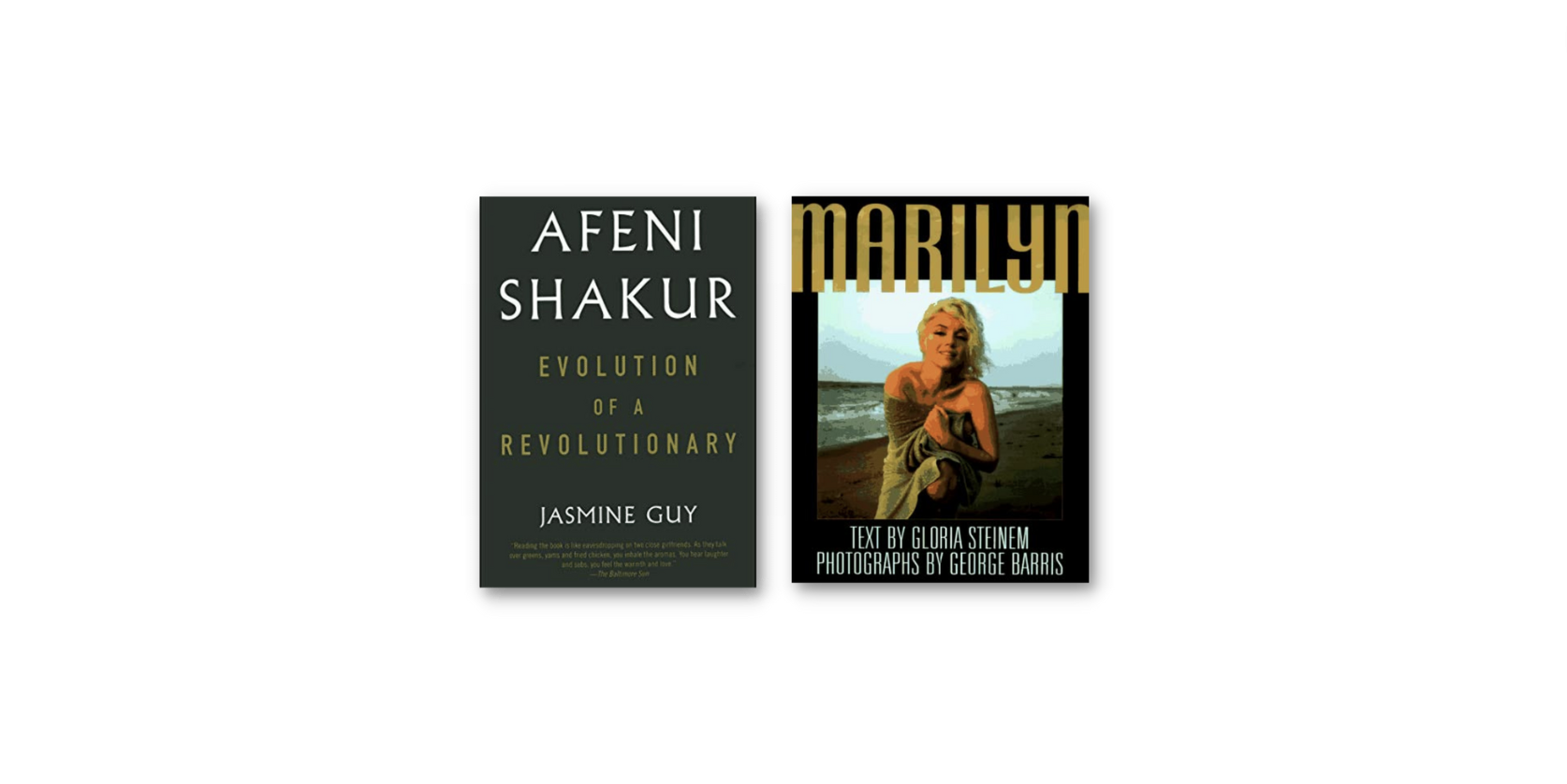

The soul of Tupac Shakur has always had a unique and profoundly spiritual way of leading me to places I did not expect, right from the day I first met him nearly thirty years ago. When I was writing Vibe magazine cover stories on the mercurial hip-hop star and actor, little did I know that I would become an alleged expert on his entire being these many years after I was there in Las Vegas where he died. But here I am penning a long overdue biography of his life, and I have spent this past year digesting all kinds of books, including two that surprised me by their commonalities: Gloria Steinem’s remarkable 1986 study of Marilyn Monroe’s short but dramatic journey; and Afeni Shakur’s breathtaking autobiography written with the actress Jasmine Guy, from 2004.

I had only thumbed through the Afeni Shakur autobiography previously but recognized that if I were to write a momentous biography of Tupac, even if non-traditional, I had better double down on all I knew about Ms. Shakur, despite having interviewed her when her son was alive, and in spite of the many times our paths crossed after Tupac’s death. Except for the way Jasmine Guy inserted herself one too many times into Afeni’s account, it was a gripping read start to finish. What I admired most about Ms. Shakur’s telling was her brutal and unapologetic transparency, and how much she reminded me of my own single mother, one who also had a complicated relationship with a son, me.

There were numerous times where I had to put the book down, laugh, cry, shout, just stare into space, because you could feel the stomach-churning trauma of Afeni Shakur’s saga socking it to you from the page. This book, undeniably, helped me to understand Tupac in a far greater way simply by getting to understand Afeni Shakur from angles I could not have imagined. To survive American racism, yes, but also to survive family traumas, and the mean-spirited foulness that told her she was not beautiful, because of the darkness of her skin, and how that would shape the woman she became, the leader she became, the street warrior with many demons, the parent who needed to be parented, too.

And the book forced me to rethink my own mother, and women like her, what they have had to endure, because of sexism, because of the many in our world who still do not value a woman, no matter who she is.

Meanwhile, I have been continually searching for parallels to Tupac Shakur’s massive celebrity and I was led to Marilyn Monroe by a Netflix film based on the Joyce Carol Oates historical novel of the same title, Blonde. I found the movie to be not only unbelievably triggering, but also yet another male content creator (in this case, the director) exploiting Marilyn in death as she had been savagely exploited while alive. It hurt, honestly, to see such an insensitive treatment of a fragile superstar as wildly misunderstood as Tupac has been, then, now.

Meanwhile, I have been continually searching for parallels to Tupac Shakur’s massive celebrity and I was led to Marilyn Monroe by a Netflix film based on the Joyce Carol Oates historical novel of the same title, Blonde. I found the movie to be not only unbelievably triggering, but also yet another male content creator (in this case, the director) exploiting Marilyn in death as she had been savagely exploited while alive. It hurt, honestly, to see such an insensitive treatment of a fragile superstar as wildly misunderstood as Tupac has been, then, now.

And although I am very familiar with Marilyn Monroe’s narrative—as I have been a fan since my childhood, and even a framed poster of her hangs in my home—something still told me to do a deeper dive, to find a book about her in the aftermath of that rotten movie. I had no idea that Gloria Steinem, someone I consider a mentor and a friend, had written a Monroe book when I was a very young and green writer many moons back. Because it is Steinem, I immediately knew that it would be a feminist take on Marilyn Monroe, not an abusive and sexist undertaking like the Netflix affair, like prior Monroe books by largely male writers.

What I did not expect via the Gloria Steinem meditation on Marilyn Monroe was the same emotional tug as the Afeni Shakur book. I knew that Monroe had a troubled childhood, I knew that her mother had been mostly institutionalized for mental health reasons, for much of Marilyn’s life, and I knew that the biological father had abandoned her. I did not know the graphic details of her childhood and teenage years, nor did I know how badly, and blatantly, Norma Jean Baker, as she was born at birth, had been used, time and again, as a young adult, and even once she had become a major Hollywood figure, beloved by many.

Afeni Shakur: Evolution of A Revolutionary and Marilyn: Norma Jean both affected me in ways I cannot quite explain, including because of my own travail as someone who has been in the public eye for some time. You want to scratch and scrape between the words and lines of both books and hug these women, these human beings, and hug yourself, too, in the process, because their pain is my pain, their struggles are my struggles, and their making something of their lives, against all odds, is my path, too.

Afeni Shakur: Evolution of A Revolutionary and Marilyn: Norma Jean both affected me in ways I cannot quite explain, including because of my own travail as someone who has been in the public eye for some time. You want to scratch and scrape between the words and lines of both books and hug these women, these human beings, and hug yourself, too, in the process, because their pain is my pain, their struggles are my struggles, and their making something of their lives, against all odds, is my path, too.

What I thought would be straightforward research for my Tupac Shakur biography ultimately became something much greater: a book, two books, that reminded me, plainly, without fluff, that I, we, have to love ourselves, figure out how, with the time we have on this earth. For the good of ourselves, for the good of the little Marilyns and the little Afenis inside us all.