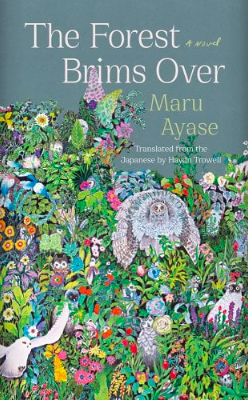

A woman turns into a forest. So begins Maru Ayase’s novel, The Forest Brims Over, translated into English by Haydn Trowell. Rui Nowatari is an (in)famous muse for her husband’s romance novels; one day, she swallows a handful of seeds and germinates. What follows is a layered exploration of what it means to create, and the gendered labor that goes into sustaining artistic creation. The Forest Brims Over is also a collection of multiple viewpoints, offering a broader look into Japan’s contemporary literary landscape.

Haydn Trowell’s translation lets the vivid nature imagery shine, juxtaposed against details of urban Japanese life. The Forest Brims Over wryly balances the mundane with the fantastical—Rui still worries about serving her husband’s editor coffee, even as she is sprouting from every pore on her body. With moments like this, Ayase’s novel shows how deeply engrained systems of gender inequity and exploitation are in our modern-day world. Yet, through alternative realities, it also gives us a glimmer of how things could shift.

Maru Ayase is the author of eighteen books; The Forest Brims Over is her first novel to be translated into English. Haydn Trowell is a literary translator of contemporary Japanese literature, such as Love at Six Thousand Degrees by Maki Kashimada.

This interview was translated by Haydn Trowell.

Jaeyeon Yoo: What drew you to this novel’s blend of nature-based surrealism and urban realism? Similarly, what inspired you to have Rui turn into a forest? Ovid’s Metamorphoses famously has women turning into trees, but here Rui transforms into an entire ecosystem, not just one singular object.

Maru Ayase: I’ve always enjoyed writing novels with a touch of fantasy. In my debut work, I depicted a world where people have different plants growing on their skin for each genealogical line. This was an attempt to visualize a person’s aging process or their relative distance from death though the use of plants and flowers. I use fantasy when I want to visualize some invisible facet of reality, such as people’s emotions, time, or their inner world, and deal with it in an easy-to-understand manner. In my novels and short stories, fantasy is a tool to depict reality in a way that brings it closer to our actual experiences.

The Forest Brims Over evolved from my interest in exploring the relationship between people who engage in expressive art and the subjects of their expression. As I mentioned, I like to use fantastical elements to visualize that which can’t be seen by the naked eye, so there was a smooth progression from the idea of a wife suffering within an unequal relationship to her becoming a plant in a water tank, thriving on emotions that are difficult to put in words.

JY: I found The Forest Brims Over to be an acute exploration of gender norms, but also a depiction of exploitation within the literary and publishing world. Could you talk more about how these two systems of inequity interact, for you?

MA: I think it’s important to pay attention to who’s creating gender norms, and whom they’re for. I’ve always felt that the “nice woman” stereotype that tends to pervade old Japanese novels—in which women are depicted as selfless, placing others before themselves, with a childlike innocence (or mystique), kind and reserved in public but sexy in private, existing primarily to affirm male characters—was always far removed from my own reality. I suspect that because the literary world in Japan has been male-dominated for so long, male writers have had more opportunities to create works featuring that kind of stereotype.

In Japan’s modern publishing industry, there have certainly been cases where male writers have published literary works about their own wives or close female relatives, withholding anything unfavorable about themselves, only to later be told that they’ve been party to an unequal relationship. Strictly speaking, there aren’t many male writers in Japan today who write personal novels about the women around them in the way that Nowatari does (though, of course, this doesn’t mean that misogyny has been eliminated). However, The Forest Brims Over doesn’t focus solely on the publishing world—rather, it’s an attempt to write, and through writing, to deconstruct the atmosphere of disregard for women that I have felt in Japan throughout my life.

JY: How do you view the role of the editor within these systems?

MA: Personally, I think an editor who can unite the streams of various works and weave them into a powerful current can have more influence on broader culture than individual authors. So I think editors should ask themselves, “Is this work, this expression, good for humanity? Is it something that might hurt certain groups due to hidden assumptions or prejudices?” Of course, it’s important for writers to consider these questions too, but I would like editors to act as reassuring gatekeepers, rigorously scrutinizing new works.

JY: The Forest Brims Over insightfully pointed out how gender norms also affect men and our expectations of literature—such as how Nowatari Tetsuya (Rui’s husband) is not content with his romance novels, as successful as they are. What do you see as the link between society’s expectations for genre and gender?

I think it’s important to pay attention to who’s creating gender norms, and whom they’re for.

MA: Society’s expectations when it comes to genre are more or less just broad assumptions. People often assume that certain genres are more geared for female readers and that others are more suited for men, but that kind of assumption only serves to crush newly budding works and deny us fresh, invigorating ideas. I wish they would go away. Whenever I find those kinds of assumptions within myself (and they’re absolutely there—they’re never completely absent, and I feel embarrassed each time stumble on one of them), I feel the need to carefully weed it out, reminding myself that the world isn’t quite so simple.

JY: What are your thoughts on loving flawed, even problematic art? I’m thinking of how much Nowatari’s debut novel meant to his young, female editor, for example.

MA: Not being able to recognize art that is flawed or problematic is something that makes me very uneasy as a reader. As an author, I am always concerned that I may one day be seen to have created flawed or problematic works due to ignorance or a lack of perspective. Sometimes, problems aren’t fully recognized until later eras. I think it can happen to anyone that one day, a work of art that you love suddenly turns out to be flawed or problematic. It can be a difficult thing to accept, but it’s important to take a step back and ask yourself if you’ve ever had any inklings about the work’s questionable elements, and what it was about the work that attracted you to it in the first place. I think one way to help yourself after discovering something like that about a work you loved is to continue contributing to society to prevent similar flaws and problems from repeating. This kind of perspective is only really possible for those who have had a close relationship with such works and issues. I know it’s difficult, but it’s important to remember that any work, no matter how wonderful it may seem, can have its own inherent flaws.

JY: Theorist Judith Butler describes gender as performative, a repetition constantly performed and enforced by society. I appreciated the range of characters in The Forest Brims Over; some overtly struggled with gendered expectations, while others seemed to find meaning and pleasure through performing their variously gendered roles. How do you see performance interacting with societal norms and artistic aspirations?

MA: I believe that social norms continue to exist because of the attitude that it has long been commonplace to label and categorize people, and because of the belief that norms can easily function as an axis for evaluating any discrepancy when competition arises within the categories created by those labels. Norms can be fun if they are successfully enacted, and painful when one fails to conform to them. That being said, they are only meaningful within their categories. Personally, I hope to one day see a society where categorization isn’t a prerequisite. However, I also understand that there are people who see things differently than I do, who consider those labels important parts of their own personal identities.

JY: Speaking of norms and expectations, Rui becomes “a character in a fable,” as the novelist’s editor describes—automatically equated with her character. Do you have more to say about our assumptions about the “muse” and fictional female characters?

The Forest Brims Over is an attempt to deconstruct the atmosphere of disregard for women that I have felt in Japan throughout my life.

MA: I believe that reality and art are mutually intertwined. First you have reality, and then, a little later, art is created to interpret it. The next generation grows up reading or watching said art, and in turn, creates the next reality. As a child, I remember making all kinds of subconscious judgments about how female characters are treated in works of fiction—like whether or not they are given power or wisdom, or what kind of image the author is trying to create for them—which ultimately led to me either liking or disliking particular characters and the works themselves. It’s scary to think that art is made up of all these inherited assumptions, but at the same time, I like to think that the strength of art lies in its ability to deconstruct those same norms and traditions.

JY: Yes, and The Forest Brims Over is extremely preoccupied with the life-altering forces of fiction. The novel’s last conversation is more of an impasse—neither Rui nor Nowatari is sure of how to make art within the cutthroat modern world. I was moved by the tenderness that Rui still has towards her husband, and her desire to not continue this territorial conversation around gender. Do you feel there might be alternatives to the cyclical systems of violence, competition, and misogyny?

MA: That is a very difficult question. One thing is certain: the joys of being in a relationship simply cannot arise from [these] cyclical systems. You can act all-powerful in a small community, such as in a family or a company, domineering over others, occupying every resource, oppressing everyone else—but you’ll always feel lonely. You may tell yourself that you aren’t lonely, but you are. The forest was an impasse, but it was fortunate that Nowatari and Rui were able to get across to each other in its depths, and that Nowatari was flexible enough to allow that conversation to take place. To me, that passage within the novel is a sort of prayer. Perhaps we can open up a different path when we have a greater awareness of value and gain—not just of “commercial success” or “power,” but of the joy of being in a relationship.

About the Translator

Haydn Trowell is an Australian literary translator of modern and contemporary Japanese fiction. His translations include Touring the Land of the Dead and Love at Six Thousand Degrees by Maki Kashimada, The Mud of a Century by Yuka Ishii, and The Rainbow by Yasunari Kawabata.