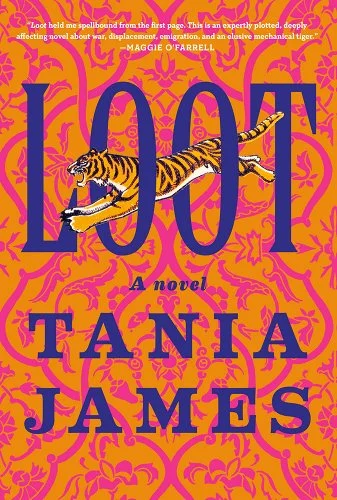

Tania James’s novel Loot is a deeply affecting, deliciously imaginative spin on how 18th century Mysorean Ruler, Tipu Sultan’s infamous automaton—”Tipu’s Tiger”—came into being. James, in her typical out-of-the-box imagination, has given voice and life to the (historically unknown) makers of the life-sized mechanical tiger, fully equipped with sound and movement, mauling a British soldier, currently on display in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum.

17-year-old woodcarver, Abbas, is called to Tipu’s court in 1794 as an apprentice to French clockmaker, Lucien du Leze, to build Mysore’s first automaton—a much needed symbol of Tipu’s ferocity in the aftermath of Mysore’s humiliating defeat by the English. But the grandeur of the object and Abbas’s apprenticeship is short-lived in a crumbling kingdom. In 1799 as war approaches close, du Leze escapes to Rouen with Jacques Martine (Tipu’s armorer) and his daughter, Jehanne. Abbas, however, is held back as the British conquer Mysore—killing Tipu, looting Tipu’s Tiger and other artifacts. Eventually, Abbas reaches Rouen only to find du Leze is dead and Tipu’s Tiger now belongs to Lady Selwyn—the widow of a British East India Company Colonel. Angry at this twist of fate, Abbas devises a scheme with Jehanne to steal the object, diving headfirst into adventure and trouble to reclaim what he considers his only shot at a legacy.

The novel, with the striking anti-colonial automaton at its center, interrogates the shifting ownership and symbolism of plundered colonial art and, through it, examines the brutal legacy of colonialism. James, known to write unique perspectives, tells me, there’s something exciting about finding doorways into an experience that’s not her own. Her delight is palpable in the range of voices she brings to Loot—from the opinionated omniscient narrator offering biting, darkly comic observations of the colonial period, to an English sailor’s tales from the sea, to Tipu Sultan himself, revealing vulnerabilities atypical of a fierce leader.

Tania James, author of three novels and a short story collection, has work in Granta, The New Yorker, The Oprah Magazine, and One Story, among other places. She’s an associate professor of English at George Mason University, where once upon a time, I had the honor of learning craft from her. It felt surreal to speak with Tania, this time in a different capacity—about art as legacy and the artist’s control over it, deconstructing the notion of belonging, erasure in history and more.

Bareerah Ghani: I want to start with Abbas—he is the hero, after all. There’s a particularly striking moment when Khwaja Irfan tells Abbas that one of Tipu’s wives, Zubaida Begum, is “a poet, an artist like you.” We see something rise in Abbas, this “want given witness.” I love that phrase and that sentiment which points to this need of an artist to be seen. How do you contend with this sentiment and need against the clichéd idea, “art needs no public validation”?

Tania James: For me, much of the delight in making art lies in connecting to a reader, in the unique collaboration between a reader’s imagination and my own. I recognize Abbas’s need to connect with a viewer. He thinks of his art as an extension of his own self that will live on, thereby granting him a kind of immortality. I think his flaw, perhaps, is in thinking that he has any control over what survives and what doesn’t, and to what extent he can will himself to make something that will last, or that will outlast him.

BG: It’s really interesting that you brought up Abbas’s desire for a legacy. Both him and du Leze, at different points, view the making of the tiger as a legacy they’re creating for themselves, something that survives beyond them. But through the course of the novel as the colonizers plunder the land and Tipu’s wealth, we watch the tiger being claimed as Tipu’s and Abbas and du Leze are erased from its history. To what extent do you think an artist’s vision of creating a legacy is futile when working under colonial rule?

I’m keen to see how the writer plays with and manipulates history for narrative effect. What emotional or unexpected truths are unearthed?

TJ: I actually think it’s futile for any artist of any age to think that they can control their own legacy, but I also hold to the notion that the artist is present in the art, whether or not their name has been erased from it. I particularly feel this with visual art, in the cuts or strokes or lumps of paint that suggest the presence of the artist. Does knowing the artist’s name necessarily give them an identity any more than those little signs, which feel as personal and idiosyncratic, maybe even moreso, than their own fingerprint? I’m not sure, but it was fun to consider this from multiple angles in the novel.

BG: How do you think the legacy of the colonized artist can be reclaimed and preserved?

TJ: Part of the challenge in writing this novel was in contending with large gaps in information. For example, I searched a long time for any information about courtly life during the reign of Tipu Sultan, and found nothing. (By contrast, you could probably find a walk-in closet worth of volumes devoted to courtly life during the reign of Henry VIII.) At first I thought I needed to write around these gaps in information, by avoiding what I couldn’t find out, which would’ve resulted in a ten-page novel. So I decided to reconsider my devotion to “facts” and instead speculate on what could have been, by completely fabricating these characters. I think that led to something more interesting, if not always factual, and was a way for me to lay claim to what has been erased.

BG: Yeah, it’s kind of like opening up a conversation.

TJ: I used to worry that a reader would come to the novel with the assumption that they were reading history. Again, this goes back to relinquishing authorial control, but every reader has to arrive with their own preconceptions and notions. All I can do is try to make clear in the end notes of the novel that this is, like all historical fiction, as much speculation as it is history.

BG: In your author’s note, you mention that the verse that appears throughout the novel (“Were an artist to choose me for his model—How could he draw the form of a sigh?”), is penned by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s daughter, Zeb-un-nissa. You state that including the verse was your way of inviting inquiry into a figure whose work has gone unnoticed in history. I’m wondering if you can talk about your discovery of that verse and how you came to envision it as an integral part of your novel?

I think it’s futile for any artist of any age to think that they can control their own legacy.

TJ: While I had a hard time finding anything about Tipu’s Court, I did know that Tipu was a great appreciator of Mughal ways and traditions. So I read a lot about Mughal courtly life, thinking that he might have drawn from it in certain ways. In doing that research, I came across a poet, Zebunissa. She was a daughter of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, not only a poet but a patron of the arts. There’s only one book of poetry that’s been attributed to her: The Book of the Hidden One, which was also her pen name: “The Hidden One.” Her verse, its melancholy and inquiry and wit, was breath-taking to me. And I liked the thought of something as small as this having power over Abbas, the first time he hears it.

By including those lines, and others like it, I wanted the novel to speak back to the past and give a sense of ongoingness, even after you turn the final page.

BG: I was really taken by the range of voices and perspectives. It adds depth to the novel’s underlying premise of shifting narratives and the idea that history is essentially the stories we tell about ourselves, passed down through generations. I find that the novel raises some interesting questions about the validity of history, particularly when the perception of Tipu’s tiger changes—from being a symbol of his ferocity to proof of Tipu’s defeat. I’m curious about your thoughts on the value of historical records and how you grapple with the possibility that the truth might never be accessible to us?

TJ: When I read historical fiction, I’m more interested in the writer’s position toward history than I am with any concept of “the truth.” I’m keen to see how the writer plays with and manipulates history for narrative effect. What emotional or unexpected truths are unearthed? (I have different expectations of history texts of course.) In terms of research, sometimes a lack of information can actually allow for a certain degree of wonder and mystery—can leave room for my own imagination to stroll through. So this, I find, can fuel rather than stunt the writing process, at least for me.

BG: At one point when speaking with Rum, Abbas says, “I have no people.” To this, Rum responds, “That cannot be true. Every man belongs to a people, even if it’s the people he serves.” I’m curious about your thoughts on this notion of belonging, what does it mean, and what it could mean for the identity and sense of home for the colonized?

TJ: I love how you’re seizing on that word “belonging.” A few years ago, I visited the fort of Srirangapatna, where Abbas lives at the outset of the novel. It was in visiting the fort that I realized how important it was for people to live within the fort walls, how it instantly meant you were protected from attack. That sense of protection is what belonging to a state or a nation, in those days, could give you. So for Rum, who has been exiled from his hometown in Tamil Nadu, and who has wound up in a small country village where he is the only Indian for miles, belonging to a household means protection. It’s a kind of currency. But as the novel goes on, he begins to suffer some of the more corrosive effects of belonging to a people that doesn’t necessarily see you as equal.

BG: You’ve built up this mystique of Tipu’s wives who, we’re told, are being held up in the zenana so “they can’t see and cannot be seen”. But then the omniscient narrator admits, “they know how to see what they are not meant to see; they’ve been seeing this way for ages.” In this depiction of oppression and resistance, I see the novel offering a parallel to its central theme of colonialism and speaking to how seeing, being aware is the first step to resisting subjugation, to being decolonised. I’m wondering how you deconstruct all this and what your thought process and intentions were, particularly in writing Tipu’s wives as these clever women who took back their power, even if in minute, less-obvious ways.

TJ: Those lines that you mentioned—that was a moment in the writing that surprised me. It was one of those moments where the novel was running just past my fingertips, where the narration leapt the track of where I thought it was going, and shifted into the mind of a woman’s perspective—a woman who wouldn’t be considered one of the “main characters.” And then switches again into the head of a little girl. There’s a good reason why narratives are structured around protagonists and heroes, but maybe because this is a historical novel, and I’ve been thinking a lot about erasure, I kept wondering about those fringe characters—how are they experiencing the scene? At the same time I want to preserve some mystery about them.

There’s a haunting painting by Titus Kaphar that hangs in the Portrait Gallery, which I’ve thought about often, called “Behind the Myth of Benevolence.” In it, a Black woman peers from behind a portrait of what seems to be Thomas Jefferson, though his portrait is drawn back and distorted, like a curtain pulled part way. Her stare is bold and confrontational, but we’re not told who she is or what she might be thinking. We’re forced to look at her through a disruption in the form that we’ve come to take as truth: the presidential portrait. This is partly my own aim when I quantum leap into the minds of these women, on occasion. It’s a way of drawing attention to what has been neglected or reduced to outlines, or simply missed.