A Love That Goes Bone Deep

The Bone Friend

I don’t know how long I had been dead when the girl found me. Long enough that my bones had gone dry and sunk into the earth part way; and that animals now gave me only a cursory sniff; and that my skull was white and wind-shined enough to catch her eye.

She didn’t have to dig me out, but she did. And it turned out, I still mostly fit together. At first I wobbled hopelessly, more like a newborn fawn than a long dead fellow. It made her laugh. The wind felt tickly in my vertebrae. I clinked lightly.

The more we walked, the more I remembered how it felt to stand upright. It is, after all, what bones were made for. I strode with surety. I smiled with all my teeth. I bounced my patella from knee to knee like a ball. She laughed. She held my hand softly in hers.

At nightfall, she took me to the edge of the forest, where her house stood aglow across a darkening lawn. She said I’d better not come inside, but asked if I would wait for her. I don’t think she understood how very little else there was for me to do in death. So I agreed and she nestled me back into a thicket for the night, curled up with the foxes. I did so happily; I watched the owls come and go all night and didn’t even need to dream.

The next morning she came back for me and we lay in the meadow, under a sun so warm I could almost feel it. I told her about the raccoon that had carried off my ring finger during winter—not a great story, I know, but death had been uneventful lately. She looked at me with pity and touched the nub of empty knuckle and, well, needless to say, no one had ever touched me quite like that.

She was lovely, with eyes so alive, cheeks so round and flushed with warmth. At this point, you may want to hear that she was just like a girl I’d loved a long time ago, when I was alive, but the truth is I couldn’t tell you.

When she kissed me, sweetly and clumsily, for the first time, her teeth clunked against mine. She insisted it was okay, cute even, but I was unsure of the way they wiggled loosely in my jaw. I didn’t want to scare her away. She gripped my hand and told me she had never felt this way before.

She wanted me to meet her friends. She wanted me to go to a dance. I would have to meet her parents.

The suit was borrowed from her brother. It hung loosely off of me. Her father stiffened when he saw me, shuddered when he shook my hand. “If you hurt her, I’ll . . . well . . . ” Her mother straightened my tie and pushed us closer together, camera in hand. “Smile,” she instructed. Hers faltered when I did.

We rode in the back seat of her brother’s car, our hands resting together on the seat between us. I watched out the window as the world flashed by. The speed made me dizzy.

The dance was held in a high-ceilinged gymnasium. All around us, others whispered and pointed, and her friends spoke too loud and too fast. But when we danced, her head rested warm on my clavicle and pinpoints of colored light spun across the ceiling like the greatest night sky I’d ever seen. We swayed and we swayed until her body was damp and alive with sweat against mine. Yes, I suppose I was in love then.

She wanted me to stay in the house. Her bedroom was out of the question, so they settled on a box in the garage. It was not so bad. During the day, I waited for her at the edge of the school yard. Other girls would stare at me, whisper to each other, wave hello and then giggle. She told me they were jealous, and they thought I was mysterious. Her lovely, soft face flushed with excitement as she told me. I put my arm around her shoulder and she clutched my rib cage as we walked.

After school, she’d bring me upstairs to lie on her bed while she did homework and argued with her mother about the inches in the door. She played music over the clinking of our teeth. In the evenings, I sat, upright and silent, through dinners with her family. I sat on the couch, her draped over me and a blanket draped over her, my hands laid carefully in her father’s line of sight. The television cast blue and yellow light that glinted off my carpals, her hair.

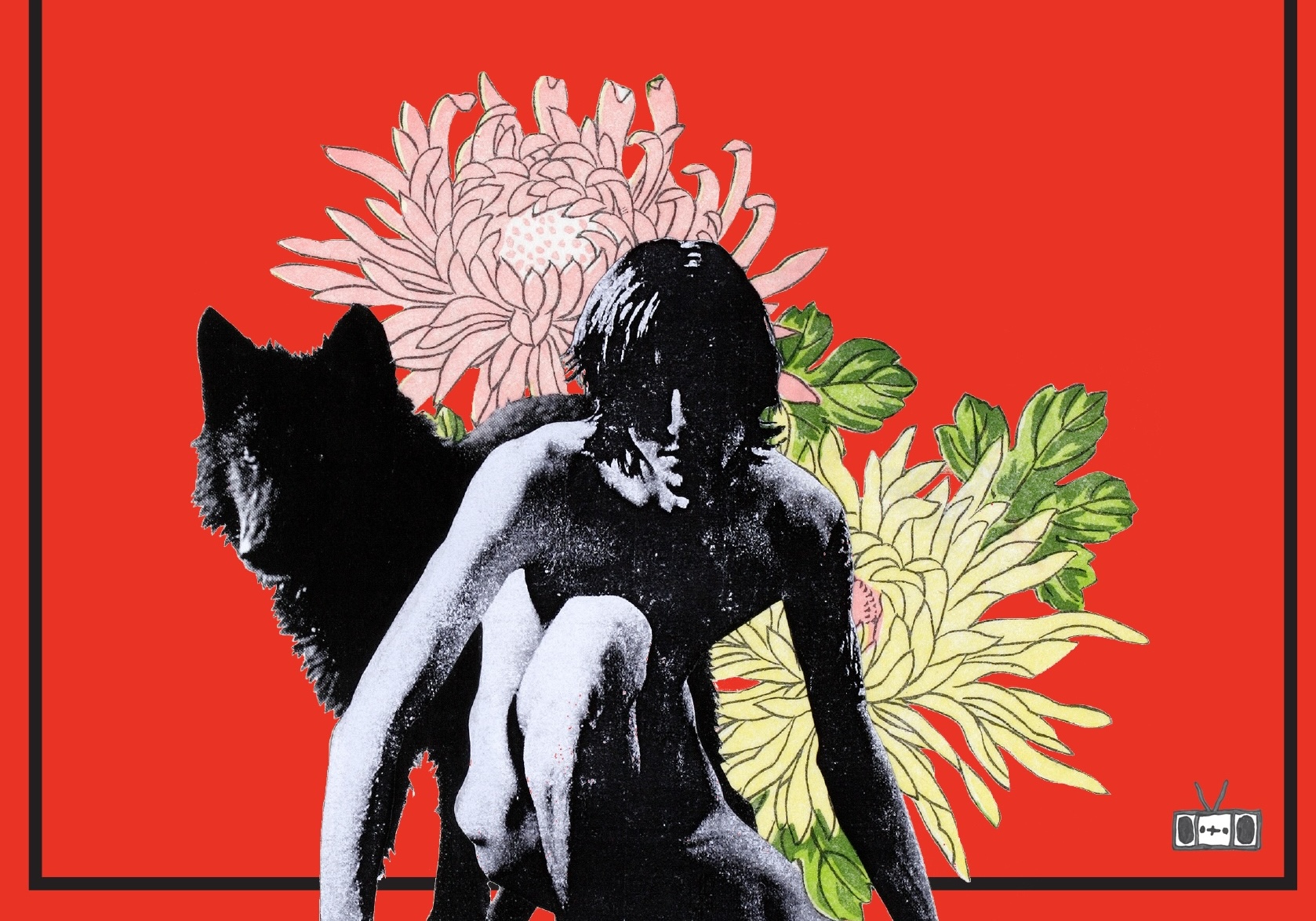

One night, at last we were alone in the house. She was flushed and nervous in the dark, her whispers insistent. I was afraid my edges might be too sharp and I tried to keep my hands still, but she pressed them into soft places. She panted and pushed against me but I was afraid—of hurting her and of disappointing her. Afterward, she lay her head on my chest and that was the part when young lovers usually talk about heartbeats, but of course, I, well. . . .

In the silence, she asked instead how I had died but I couldn’t recall. This disappointed her, I remember that much. I lay and watched the fan whir overhead and wanted to open a window, to feel the night air.

She asked me not to walk her home from school anymore. We still lay in her bed in the afternoons, or in the sunny grass in the yard. Sometimes, though, she had other things to do. Sometimes she left me for days at a time. I didn’t mind at first. It is not hard for the dead to pass the time.

But even when she let me in, it wasn’t the same. She wanted to know why we didn’t talk more, why I didn’t tell her things. I couldn’t explain how I remembered my life the way one remembers a dream, that is, hardly at all. I couldn’t explain how little I had to tell her. It may surprise you, but it’s very hard to be interesting when you are only bones.

In those days there was something living under my ribs. It kept me up at night with its scurrying. I knew that other boys had noticed her now; I could imagine how they flexed thick arms and talked among themselves, about all the things that they possessed and I did not.

And then, there was the party. She sounded impatient when she asked me. But she clutched my hand and ran her thumb over my missing knuckle, warming it as we walked. Her moon pale legs gleamed and fireflies blinked around us. I caught one in my hand like a tiny cage; its glow flared and faded, gold against my bone fingers. She kissed me—looking back, maybe that was the last time.

The sounds of the party drowned out the thrum of insects before we saw it. A boy’s parent’s lake house, she told me breathlessly, a junior. He invited her himself, during third period. Inside, the heat of young bodies pressed in like a damp August day. Music throbbed through my jaw. Her hand was still in mine; I clung to it as she led me into the pumping heart of the room and I couldn’t hear her words as she shook loose and slipped away.

Bodies bumped and jostled me and I thought my bones were unraveling then as I glimpsed her across the room with her hand on the junior’s chest. Some chattering girls pressed in. What was dying like, they wanted to know and, can I touch your skull? How old was I anyway, and how long had I been dead? They were disappointed by my answers, grossed out by my smoothness to the touch. I tried to tell the raccoon story, but they were not charmed.

How long had I been dead? How many cycles of the moon, of the seasons, of the tender cicadas burrowing into and out of the earth all around me? I missed it then, the hug of sun warmed soil, the soft silt between my bones, the stars overhead, and the semi consciousness when time became endless and also nothing at all.

I made my way somehow to the porch. Outside, moonlight fell on the lake. The woods here were thick, and comfortable, rustling with quiet, unobtrusive life.

At some point, she came out and sat beside me, briefly. She said she was going to another friend’s house and I should head home without her. I told her I was leaving, and she said that she was sorry. Then, that’s right, then was when she kissed me last, just quickly, looking over her shoulder. I know that she was lovely. Much more than that, I can’t recall.

Because this was all some time ago, a season or a snowfall at least. Now my bones feel loose and formless and I’m not so sure I would fit together again. A mouse makes its nest where my eye would be, and I can see stars and hear the loons on the lake, and the night creatures come and go, and I don’t expect I’ll be dug up again.