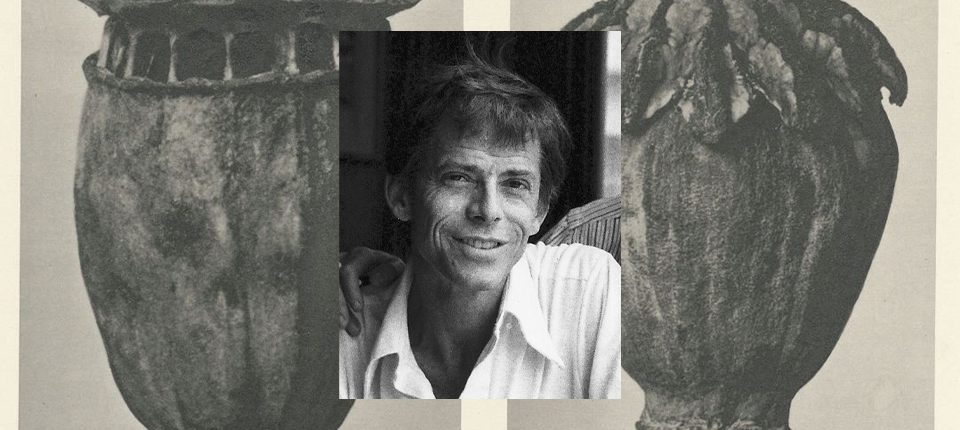

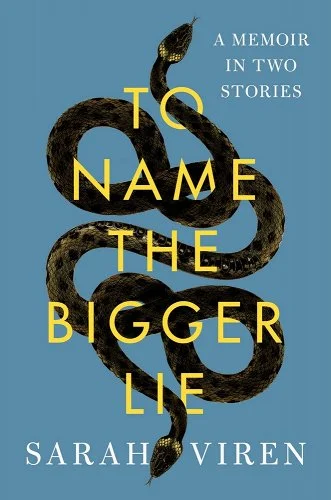

In 2019 Sarah Viren’s wife, Marta, was subject to a Title IX investigation for sexual misconduct. The allegations, which appeared via Reddit posts and emails, were that Marta had offered students wine during office hours, requested sexual favors, and threw wild parties. Viren knew the allegations were untrue—she’d never thrown a wild party with her wife, and the names of the accusers failed to line up with actual registered students at their university— and yet she couldn’t stop herself from occasionally doubting her reality.

At the time, Viren was on the academic job market, and she would later discover that it was an acquaintance, Jay, a finalist for a job that Viren had been offered, who had spread the lies to derail Viren’s career.

These events, it turns out, unfolded in Viren’s life as she was working on a book about conspiracy and truth through the lens of her high school philosophy teacher. Dr. Whiles was a man who was both inspiring and harmful, who taught students to think critically and develop their own set of values, but who also pushed religion and holocaust denialism.

Sarah Viren’s book To Name the Bigger Lie weaves the stories of Jay and Dr. Whiles together, using them to discuss themes of trust, doubt, and deception and to ask the question: how do we know what is real?

I spoke to Viren on Zoom to ask her about punishment, reckoning, and hoping for redemption.

Jennifer Berney: I came to your work through your viral essay in the New York Times Magazine and, like a lot of people, I found it fascinating because of the complicated ways it intersects with #MeToo. I’m curious about what you dealt with in terms of going public with your story, knowing that it might be used to undermine #MeToo or Title IX, to push the idea that false allegations are common.

Sarah Viren: One way of understanding what Jay did was that he weaponized Title IX and he used stereotypes about gay people to prop up the lies that he was telling. There are people who want to dismantle Title IX entirely as it relates to sexual assault and misconduct. And so I tried to make clear within the story that I think Title IX has value. But then, once the story came out, I knew I couldn’t control how it was used beyond just not giving interviews. Somebody wrote to Marta for Fox News, asking her for an interview. In the end, Marta ended up giving one interview to a Spanish newspaper, but we really talked to the interviewer beforehand. And then, after that we just had to let it go. I had to weigh: what are the costs and benefits of telling the story? It felt like the potential harm was that it would be weaponized—which it was—but I felt like the benefits were that it could create a more nuanced discussion of some of these issues.

JB: Does your decision to tell the story align with a philosophy of telling the truth simply because it’s the truth?

I had to weigh: what are the costs and benefits of telling the story.

SV: It feels simplistic to say let the truth out and everything will be okay. But when this article came out, I heard from so many people with stories, and a lot of them were women and people of color—people who are already struggling to have their truths recognized in the larger public sphere. They told of cases in which they had been similarly manipulated, and they didn’t have the clear proof that we did. And I thought that is the value of telling these stories, if it helps others make sense of their experiences or feel less alone.

JB: You write about how you initially wanted Jay’s identity to be revealed for accountability. But then other people found him and outed him, and it’s no longer what you want. But the book continues to long for him to take responsibility and redeem himself on some level. Can you speak to that longing?

SV: Yes, I’ve been thinking about that for a long time, probably even before that happened. One book that was really influential was Lacey Johnson’s The Reckonings. She visited Texas Tech, where I was doing my Ph.D. and people asked her in the audience “What do you want to happen to this man that did this awful thing to you?” and she thinks through that in The Reckonings. I’ve been interested in how we reckon with harm out outside of a simplistic view of punishment. I don’t think that punishment always allows people to reckon with what happened.

What I kept wanting from Jay was a confession. And so I was thinking a lot about confessions. Culturally we’ve gotten used to this idea that a confession brings us closer to the truth, and to a reckoning with. I thought if Jay would just say, “Hey, I did this. I’m sorry.” I really felt like I could forgive him.

JB: Do you think what we might really want through the confession is to feel like the person who harmed us has the potential to change?

SV: Yeah, it’s funny. I have this friend who I talked to a lot during that time period, and she would always say, “I want him to be punished and I want him to hurt.” I think a lot of people feel like if somebody harms you and is punished, it’s balancing something that was imbalanced. But no, I don’t feel that way. If I could know that Jay felt bad and was actually working to not do something like that in the future, that’s what would feel better.

I shouldn’t read comments online, but one person commented on the article something like: “Yeah, it’s fine for you not to name him. But how are you going to feel when he does this to somebody else?” And that does feel bad. That will feel awful. But I don’t know where he is now. I don’t know what name he’s using. I don’t have any ability to stop him.

JB: It seems like we have a cultural narrative about having a responsibility to others once we’ve been harmed by someone.

I’ve been interested in how we reckon with harm out outside of a simplistic view of punishment.

SV: I think that’s a complication of the way we imagine these roles. I was always uncomfortable with the idea of victimhood, because there’s a sort of passiveness to that. But the other extreme can also be this idea that you’re an accomplice if you don’t do enough. Marta was really helpful in thinking through it. Marta would say a lot of times,“If anybody’s responsible it’s these universities that allow this to happen.” Jay was eventually removed from his job in academia, but allowed to quit, so there’s been no public accounting for his actions, and that has to do with institutions not wanting to be sued. And so, there need to be ways that we hold people accountable in situations like this, but it doesn’t make sense to require whoever is victimized to do that. That doesn’t mean that you don’t feel bad. After he was identified on Twitter and elsewhere, a couple of people came forward, men who said they’d been harassed by him. And one of them said, “I feel really bad that I didn’t say anything because maybe this wouldn’t have happened to Sarah.” I think that’s another example of somebody being victimized, and then feeling like it’s their fault because they didn’t stop that person from continuing to victimize other people.

JB: How does this story about Jay connect to the story about Dr. Whiles, your high school philosophy teacher?

I had already started writing this story about my teacher in high school who taught us conspiracy theories but who none of us had really ever confronted. And in that process I kept thinking about how if only we had talked to each other earlier, or if only an adult had intervened and said like this shouldn’t be happening, we might have been able to at least understand it. My friend, who I call Gail in the book, a Jewish immigrant from Latvia, got close to Dr. Whiles and ended up really confused, and, I think, a little depressed by him pushing her towards holocaust denialism. I often think: Wow, If she and I had just been able to talk, it might have helped her push back against some of the gaslighting that was going on in his classroom. And so I’d been thinking about that.

I felt like these two stories really spoke to each other, but I could not articulate how. When I sold the book on proposal, I couldn’t structurally tell how it was going to work. But rather than braid these two stories together, I wanted to show the interruption of the Jay story, and the way that often those interruptions in life will help us understand something. I think that so often something unexpected happens that we feel like is unrelated to whatever it is that we’re dealing with, and it ends up being the thing that brings clarity.

And so what happened with the Jay story was that there were moments in which I was doubtful of myself in a way that was very similar to how I felt doubtful of myself when I was younger, and there were moments where I felt like: why is nobody freaking out? And so that’s what I tried to write into. But then figuring out how to structure it was hard beyond the fact of starting a story, and then having the Jay story interrupt it. I did want to do something structurally different, and I thought about Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, where the cave has four parts and so that four-part structure felt essential to the story itself in the end. For the last part of the book, I started doing these imagined dialogues.

JB: In that last section you include real present-day email exchanges with Dr. Whiles, and I found myself feeling really nervous for you as a narrator in the book, navigating those email exchanges.

You know, I had the book mostly written, and I really thought, Oh, I’ll reach out to Dr. Wales. I really didn’t want him to agree to the conversation because I didn’t want to deal emotionally.

JB: I was so surprised at that section because I wasn’t expecting him to become a real, present-day person.

SV: Yeah, I wasn’t either. I was thinking, I’ll just imagine him, and it will be okay. And he did initially say no and I could have left it at that. There was a journalist part of me that was like, no, you just don’t do that. You have to keep pushing. And I did. I think the people we write about, even when they harm us, they still deserve the respect of being fully-formed. Because nobody is a monster, right? And so I was really thankful that he responded, and I could see his pride and his vulnerabilities, and I was able to read some of his moves for what they seem like now—blustering, you know. I don’t think that I realized when I was a kid that he was sort of enamored with his own greatness. I just thought he was great, and so I think, seeing that weakness helped me to see him as more human. And when he finally cut off the interaction, I felt the same rejection and feeling of being shut down that I used to feel in high school.

JB: By the end of that section it feels a little unresolvable to me, the way Dr. Whiles was both a pivotal figure in your development and someone who did you great harm. Does that seem right?

SV: Yeah, I think that’s right. And I think it’s made that much more real by the fact that we get to see him in his own present day terms. It’s so much easier to think that those that harm us are just bad people, or to write them that way, but also in your life to create a narrative in which they exist that way, because it’s just easier to deal with them.

There are awful people in the world, but in these two cases—well, Jay is a complicated person I feel sorry about. I’m not sure that he himself helped me. But Dr. Whiles did. And so the idea is to acknowledge the complexity of it, and sit with it and exist with it, and then also to sit with the fact that he didn’t change. You talked before about me wanting to feel like Jay had changed. I think with Dr. Whiles, I was hoping for something similar.

When he became real, I was able to reckon with who he was, what happened, and the complexity of him in my life. But it also didn’t feel like he acknowledged or could acknowledge having harmed anybody else, or that he had necessarily grown.

I will say there was one person, a friend I had in high school. He was very religious. He wrote in my yearbook, something about how I was going to hell because I was bisexual. He’s now a pastor, and I interviewed him in the book. When I told him what I remembered he recognized that it was real, and he felt bad that he hadn’t recognized it at the time. He said, “You know, I’m sorry. I think I just didn’t have stakes in the kind of harm that Dr. Whiles was causing.” But the fact that he could acknowledge that—I mean it’s not the same as having the perpetrators grow, but it did feel like okay, there are people that are growing. We’re developing and changing. They’re just not necessarily the people we want.