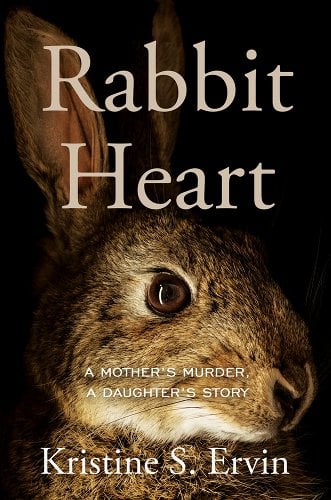

When Kristine S. Ervin was eight years old, her mother, Kathy Sue Engle, was violently abducted from a shopping mall parking lot in Oklahoma and murdered. Though Ervin’s debut memoir, Rabbit Heart, does include an eventual resolution to the case in which Kyle Eckardt was convicted, the narrative is not categorizable as true crime, and it is not a story that centers itself around the pursuit of a perpetrator. Instead, Ervin seeks answers to a different set of urgent and moving questions: What power does language have to harm and to heal, and where do we turn when there is a pain that cannot be quantified or described in words alone? How can we name violence, reckon with violence, and tell a story about violence without sensationalizing or repeating harms? And what does it mean to seek resolution within a judicial system when the grief for a lost mother is searing and unending?

With an unwavering gaze and in sharp, poetic prose, Ervin asks readers to bear witness to the violences her mother experienced and examines how patriarchal systems incite further violence through language, through silence, through the story of our bodies, through absence, and through generations. Rabbit Heart is a story about the ache of an everlasting grief, about growing up under the shadow of an impossible loss, and about how language can become a form of light in the dark, but only if we are ready to face the truth of a life in all of its complexity.

I had the opportunity to speak with Kristine S. Ervin, who I know as a colleague and friend, over coffee about the sinister ripple effect of violence, accepting that certain kinds of wholeness will never be possible, and the power of reclamation.

Jacqueline Alnes: So often when we talk about grief, there seems to be a pressure on the person delivering the story to offer an ending or a resolution. It’s clear in the book that you don’t reach closure, as this is a grief that is unending, but I do think you reach a tenderness with yourself and your own experience. To you, is closure the same thing as healing? Are there different kinds of resolution?

Kristine Ervin: The fact that Eckardt is in prison for the rest of his life and cannot be released and harm another family or woman, there is resolution and peace in that. Knowing there will be no other revisions to my mother’s death, there is healing in that. One of the most difficult things in this experience was that revision. Every couple of years learning another detail that made it more real or more horrific and knowing I don’t have to go through that, and knowing that I can make the decision not to learn more, that’s healing. Having this book, which is this physical, permanent thing, and knowing that I don’t have to add to that further, there is peace in that.

The grief, in regard to longing for my mother and missing my mother, that’s where I see that there’s no such thing as closure. At times, still grappling with violence, there is still no closure. There are times that Eckardt still shows up in my dreams. That’s not ever going to be full closure. I’m needlepointing magnets and bookmarks for the first time in about 25 years and when I started, my first thought was, I wish my mother were here because she would teach me to do the borders a certain way. I’m looking at the needlepoints she made and trying to replicate them, but my stitches aren’t the same. That’s where I think that in grief itself, there is no closure, but it’s not as brutal as it once was, because of the resolution to the case.

JA: Your memoir highlights how stories can be a form of salvation or reclamation of power, but also how language can enact further violence. The police commented that your mother’s “main mistake was walking back to her car alone.” Your younger self was reluctant to describe sexual violence you experienced as “rape,” even while you would describe the same experiences as such for another person. Was writing this memoir helpful in taking back those experiences in your own language?

KE: About a year ago, I sat with my father at IHOP because he wanted to try their new crepes. I had just come back from AWP. I was telling him about the experience of being in a community of writers and feeling like I’m among people who understand what I’m trying to do. He said to me, “Well, if you didn’t write the book for money, why did you write it?” Though I knew he would not really be able to understand what I was saying, I answered honestly, and in my own voice. I said: It is my way of claiming my experience.

I grew up with two men, with gendered violence, and this is my way of not being silenced about it any more. When it comes to my own experiences with rape, with sexual abuse, grappling with how I would absolutely call it “rape” for someone else but not for me, not only do I have the culture at play, but then I also have this juxtaposed to what my mother experienced. It’s very hard for me to place our experiences in the same category. Ultimately, when the voices are going back and forth in the book about what my experience is, I ultimately reach the conclusion that yes, this is rape, and I don’t want it in the same category as my mother’s. There is power in that. The telling of the story, the putting of the story on the page, the sharing of the story, and to break the silence against the men in my family, the men in law enforcement, the men in culture, the women who have internalized what the patriarchal thinking is, there is enormous power in that. I hope it’s something I can hold onto.

JA: You have to, I think.

KE: It’s also terrifying. My mother’s story has been out for quite some time and mine hasn’t. To have it public, that will be a new experience to me.

JA: I wonder if it will feel different having your mother’s experience out as you have written it. There is such a distinct difference between the way you bring humanity, love, and depth to her story versus the newspaper stories and police reports.

KE: But I also hope I brought to the page an awareness that it is not her story.

JA: Right.

KE: I’m conflicted about that. I’m conflicted about putting my version of the story out there, because it’s not hers. I don’t know what she would think about this, I will never know what she thinks about this. Even when people say to me, “Your mother would be so proud,” we don’t know that. Though this isn’t the version told by detectives or journalists, most of those versions being deeply problematic, this is also not my mother’s story. This is my processing of my mother’s story. My imagining what happened to her was yes, wanting to push back against the stories told about her death but it was also my desire to feel a connection to her. I did that through my own imaginations, I did that through my own experiences. That’s where the longing for a mother really comes in.

I’m also conflicted. I put a lot of violence on the page. We have a lot of writers who relish violence, who perpetuate violence through the stories they tell, and I am terrified that I’ve done that. How do you write about violence, about gendered violence, without perpetuating that violence, without relishing it, without producing something that’s titilitating or entertaining for the reader in a way that’s problematic? I don’t know that I accomplished it, but I grappled with that a lot.

JA: For me, what you asked me to do was see. You asked me not to look away. I’m thinking of the scene where you zoom out and imagine the oil field workers looking at her body, and you ask us to look at who is doing the looking and who has the power. I never had a moment where I felt like the violence was for the purpose of re-creating the violence; it was because no one had looked at her with love in those moments and had to keep looking.

My imagining what happened to her was [about pushing back] against the stories told about her death, but it was also my desire to feel a connection to her.

KE: We have that moment with the eyewitness Roy Hinther, whose name is really Ron Hinther, but as I say in the memoir, he’s Roy to me because of a journalist’s mistake. I read that scene in Greece last year with students. When Roy Hinther was on the stand talking about seeing my mother be abducted, I know that scene will always impact me, regardless of how many times I read it or perform it. I choked up during my reading multiple times. I spoke later with a friend about how that scene will always impact me because here’s somebody who was seeing her and caring about her. It was really the last person who cared about her. Roy Hinther wanting to do something, but unable to. Wanting to see my mother’s head lift up and see it in that back glass, but never seeing her head. Roy Hinther trying to work out his memory on the stand. Roy Hinther crying on the stand. Here was a moment where someone did bear witness and took the weight of that. One of the few people involved in the case who did that. That’s in contrast to detectives, that’s in contrast to oilfield workers.

JA: You lost your mother at eight. You write about this metaphorical memory card game in which you try to put together the pieces, but who your mother was becomes something of a compilation of fragments. Even as you know you can’t complete the whole, you keep trying. I kept thinking: that’s love, isn’t it?

KE: One of the aspects of grief in a loss like this is that I’ll never know. I’ve asked my father plenty of questions about her, but especially the answers I get from my father, it’s not my mother. It’s been filtered through something. It’s the husband’s reflections of Kathy Sue Engle. Especially after someone passes away, people don’t want to share the flaws, they don’t want to speak ill of the dead. Part of the lack of closure, part of the grief is knowing I will never know my mother as a full human being. I will never know what she felt like as a computer coder in the 1970s and ’80s. I will never know what it was like for her to make a decision to go into a business of her own because she wasn’t getting paid by her male employer. I will never know how she felt about having an affair. I will never know how she felt about her first husband. Those are the conversations I wish I could have as an adult woman now. What were her thoughts? What were her experiences? Especially with relationships and power.

I have the mother who dressed up as an Easter Bunny and brought a piñata to class, and that’s all I can hold onto. I’ve tried to come to accept that the memory that I have of my mother is what I have and it’s okay, and it’s beautiful, in its own limited way. The stories I get from other people are their stories; they are not her.

JA: I appreciate how you bring up gendered expectations in the way that you recollect things. For example, you imagine that if your mother had been alive, you might have been able to know your body better or have someone to validate your experiences or remind you of your inherent worth. But even in that longing, you recognize that the mother you’re picturing is idealized, one without flaws. Or later, when reading her letters, you write, “I find myself wanting to…reduce the whine.”

It made me think about how there are narratives around motherhood and the policing of what a woman should be that limit the way that women can move through the world or be in relation with other people or see themselves. The way that you admit to internalizing some of these beliefs through your work on the page is a testament to how pervasive these narratives are.

KE: That’s part of the hard part of the memoir. That’s the part of myself I would like to edit out. I would like to not have the “I” on the page that is critical and judgemental of women—my mother, myself, or other women. It’s not in the book, there’s a line that references it indirectly, but I went back to poems I wrote as an undergrad and when I realized she had an affair within her first marriage, I wrote a poem that basically called her a slut. That’s the 20-year-old who has very specific ideas about marriage that are far more simple than the 46-year-old now knows. That’s the daughter reckoning with the fact that the mother she has built in her own mind isn’t the perfect woman. I look at that poem and I’m ashamed of it. I understand it, but I’m ashamed of it. I don’t know what I would have thought had it been reversed and I found out my father had an affair. I don’t think I would hold the same judgement.

To be authentic, I needed to bring that to the page. I have leveled judgments against the perfect mother and that is a violence that I have done. I am not giving her full humanity when I’m judging her for whining or longing for her lover, or for having an affair when she had a domineering husband. All those are part of patriarchal violence.

JA: At one point in the book, you write, “I feel like I’m sinking in violence all around me and I can’t fight for a breath, much less the voice to say, I need you to be gentle and slow.” You do incredible work highlighting the sinister ripple effect of violences—the way that language can shape story, can shape belief, can become embodied, can take on too many forms to name, both large and small, but all of them polluting the way we see ourselves, others, and the way we move through the world. For you, what was it like to name these violences, to bear witness to them, and to ask a reader to do the same?

KE: The naming of the violence was my way of having to reckon with it. As I write about, I went to really brutal places in my own mind of what I wanted to do, specifically to Eckardt. I am still astounded and deeply troubled by how violent I wanted to be toward another human being. You could say it’s not as bad because I’m troubled by it, but the ways in which the violence that my mother experienced did ripple, continues to ripple, reinforces and perpetuates violence, I still struggle with my own history with that.

Part of the lack of closure, part of the grief is knowing I will never know my mother as a full human being.

When we were in the judicial process especially, it just felt like violence all around me. Not only the violence that I was learning because of case details and encountering this human being face to face, but the ways that it brought back violence against my own body. There are scenes where there are very different reactions from the men in my family and I’m questioning, how can my brother be so matter of fact about all of this? Is it because he doesn’t have a woman’s body? Is it because he doesn’t place himself in the position of imagining a knife between his breasts like I can? That violence, learning more about what my mother went through, the way it can create violence in my own body of what I want to do to somebody else, the way that it retriggers the violence that I experienced, the way that I’m imagining that violence happening again.

Part of the story and the building of the story is to try to create something out of that violence—a resistance to that violence, something that is a beautiful, made thing that will push back against everything that hurts.

JA: I found the way you wrote about your father and brother’s influence in your life to be so fascinating, as you managed to hold the love you have for them while also noting that some of the systems they uphold are ones that have harmed you and harmed your mother. How do we separate the person we love from beliefs they have that might cause harm? Is that even possible? How do you reckon with that?

KE: I don’t think I do it well. That is something I reckon with in the book and in my life, and with my father especially. He is someone I love deeply, who loves me deeply. He is someone who did his best under impossible circumstances, if I think about his experience to have cops wake him up and be at his doorstep asking if he is the owner of a Dodge Colt and learning what happened to his wife and then having two children to raise—a daughter—entirely on his own with no support, really.

I hope that in the memoir I accomplished showing my father and my brother as complex human beings that are a part of a system that harms, that harm without intending to because that is part of the problematic nature of it. I hope I have shown them as participating in a system that hurt me, that is part of the violence against my mother, but showing what is in some ways almost more disturbing, because there is a violence that they do not see, a violence that they do not recognize.

My father and my brother can easily recognize the violence against my mother’s body at the hands of someone like Eckardt or Steven Boerner, but they do not recognize the violence that comes from diminishing a woman’s experience, silencing a woman’s experience, not even caring to have that voice represented. The violence that comes from upholding other men and not being able to see how men can harm in quieter ways. That’s a thing that I don’t think they will ever be able to see, even if they read Rabbit Heart, which I told them not to. There is no reckoning, honestly. Maybe I’m too cynical, but I don’t think there is a way through. Like so much with Rabbit Heart, I’m trying to come to an acceptance there.

JA: You’ve broken so many silences in this memoir. By doing so, you’ve lit the path for others to do the same, and given them language where otherwise speaking might feel impossible. What would you say to someone who is on the precipice of sharing their story?

KE: If anybody’s on the precipice of telling their story I’d say to make sure they are ready to encounter themselves, re-encounter their experiences in a way that can be violent. Stories can harm—I’ve seen that, I’ve experienced that—but as I think about the moments in Rabbit Heart that mean the most to me, it’s when the stories connect us. It’s Roy Hinther telling his story of my mother’s abduction and knowing that he was somebody who cared for her. It’s Lesley at the OSBI, thinking about how my telling her my story impacted her to go into forensics and then she ended up helping so many people. If you’re on the precipice of telling a story and you’re ready to tell your story and you have the support system in place, I say break the silence for the chance of connection.