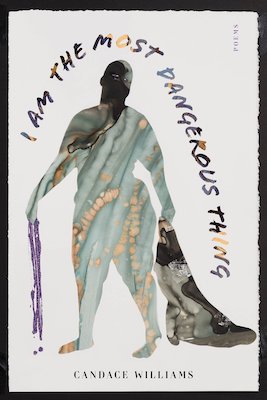

In their debut poetry collection I Am the Most Dangerous Thing, Candace Williams collages identity, political and economics matters to investigate the risks and joys of being Black, female and queer in a society where individuals and institutions are too often focused on their destruction. The seriousness of such topics belies the array of poetic forms and subjects, and especially, the many moments of beauty, and humor juxtaposed and layered to great effect. Consider this excerpt from “Memo”:

“Due to unforeseen circumstances

I am forced to lay off 20% of my friends

effective immediately.”

This levity belies a deeper reflection on the transactional culture in which we live, directed by organizations, as well as those “voluntary” overlords we choose to engage with, such as social media. Or how in “Desk Lunch Poem” Williams recontextualizes poetry past into a modern and personal setting:

“I eat leftovers

at my desk

because being a Black

woman who can always be found

working is the only reason

they let me eat”

The call back to Frank O’Hara Lunch Poems, without the era-specific whitewashing, takes off from the “I do this, I do that” form and then layers it with intention and a turn that is striking and resonant. Instead of a centralized “white gaze” it pedestals the person of color for whom there is no luxury of strolling about town at lunchtime without care. Yet despite corporate expectations, the speaker takes the agency to still create poetry on their lunch hour, if within the constraints forced upon them.

Mandana Chaffa: In this collection, there are ghazals, sonnets, bops, references to other poems and poets, and though you name some of them, I felt that there’s much under the surface that even the reader wouldn’t be aware of or needs to be, for that matter. Excuse my mangling of metaphor, but such a diversity of form reminds me of the musician who plays several instruments, and in so doing, has a far wider palette which will to improvise.

Candace Williams: The poems in this collection are my earliest poems (besides the bangers I turned in for my 7th-grade poetry project in English class). I started writing in late 2015 after my then-girlfriend (now wife), Laimah Osman, suggested I write poetry. I was lucky enough to find poetry workshops at Brooklyn Poets and the Cave Canem Foundation. Many of these workshops were focused on the concept of form and how certain forms could unlock new ideas and experiences.

The form of the memo helped me explore the life and death power dynamics that exist in the workplace and how these dynamics are reinforced (and betrayed) by language.

The first poem I ever turned in was “Memo” in Wendy Xu’s Against the State workshop at Brooklyn Poets. She suggested we think about the act of writing a memo and where memos tend to be written, and then find a subject to explore in that form. The form of the memo helped me explore the life and death power dynamics that exist in the workplace and how these dynamics are reinforced (and betrayed) by language. I had worked in school, nonprofit, and startup environments where I was called a friend, family member, or community member even though those spaces were designed to coerce and exploit my labor. I’m so thankful that this was my first experience writing a poem because from that poem on, I decided I needed to answer the questions “Why write a poem at all?” and “What experiences and ideas can each poetic form unlock for me?”.

I love thinking about repetition. Repetition can happen on the basis of sound, stanza structure, word, and/or constraint. For example, ghazals and sestinas both employ repetition. The repetition and heritage of the ghazal lends itself to an entirely different kind of rumination than what I achieve with a sestina. Even though some of the themes might repeat themselves, the experience of writing and reading “When I was 12”, a sestina, is much different than the ghazals “After the Rain” and “Fruit”. When I write in blank verse, the sound patterns are almost like a gentle breeze pushing me through something. That something can be a walk through Crown Heights and its history, through a typical Sunday in Kingdom Hall, or through the dying words of John Henry. There are exciting things that happen when I take a form that has been given to me and tinker with it. I get to hold the history of that form and comment on it with my perspective.

Even if I am writing in free verse, I am creating a nonce form for the purpose of that poem. To return to Wendy Xu’s brilliance, one of the earliest lessons she taught me was that the most important line of a poem isn’t the first line or the last line. It’s probably the second line because that is where the reader asks the question “How do these lines relate to each other?”. Wendy taught me that every time I write a poem, I am creating an ecosystem for myself and the reader.

MC: Given the variations of background, font size and document style you employ, readers’ eyes are subtly adjusting to each poem, which is especially cortex-activating. Was this something you were always planning with this collection? How important is the visual experience to your process and output?

CW: One of the core obsessions of my work is exploring how language calcifies physical and social realities. I had a few horrible years in elementary school where I was bullied for being fat, Black, and nerdy. I didn’t realize it then, but the slurs and cruel language children used to address me created a physical, emotional, and intellectual reality. I was too young to think about it then. I started thinking about this concept formally in 10th grade when my teacher introduced me to Plato’s Theory of Forms. He drew a circle on the board and erased it. Then, he reminded me that even though the physical circle is gone, the idea of a circle persists. There’s the concept of incarceration, and there’s the Crow Hill Penitentiary and Rikers Island. There’s the Whren et al v. United States decision that enables the practice of pretextual stops in policing, and there’s the fact that I avoided driving for over a decade because of what can happen to me if I’m pulled over. So, it makes sense that I am using visual forms like erasure. Language and its absence create a visual experience on the page. This helps me explore the physical, social, and intellectual impact that language has on our lives. This is why I erased texts like Heart of Darkness, the New York Times, and Whren et al v. United States. It’s also why I wrote my own death certificate by taking a real death certificate form and writing over it.

MC: There’s so much complexity in style, subject and juxtaposition in this collection. What are some of your influences, across art forms, and how do they influence this collection and what you’re currently working on?

CW: To say I experienced difficulty finding safe housing in Brooklyn and New York City is an understatement. For most of the time I lived in NYC, my apartments were fraught at best and unsafe at worst. This reality, coupled with the fact that I was not given much access to art (outside of music instruction) in school, led me to seek out artistic experiences on a weekly basis. My first job was teaching K-5 science at a school for children in foster care in the South Bronx. Sometimes, after school, I bought single Family Circle seats at The Met Opera (the opera equivalent of nosebleed seats), or saw films at the Film Society at Lincoln Center by myself. When I realized the City of New York offered a Cool Culture arts pass to teachers, and that I could get into MoMA, I started spending a few hours per week there. I would always beeline for the tiny room that holds Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series. I got to take in the work of artists like Sanja Iveković, Fluxus, and Juliana Huxtable over the course of many visits. I spent quite a bit of time at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. I probably saw at least two concerts, films, operas, or theater productions there per week. The work of Rhiannon Giddens, Tanztheater Wuppertal Pina Bausch, The Creole Choir of Cuba, Phillip Glass, Anne Carson, and William Forsythe influenced me. I took in most of these shows alone, and I’m thankful for that.

Weekly access to visual art and performance is something I really miss about New York City and Brooklyn. Sometimes, moments in a performance that are seemingly disconnected from my life make me think about something in a totally new way. I remember watching Tosca at the Met. I smelled the smoking thuribles that the altar boys carried across the stage during the “Te Deum” and rushed home to write “Nostrand Avenue Dirge.” That scene influenced many of the poems in this collection—You have a solemn, grand Catholic mass filling the stage while a powerful man is using that space and music to engage in his fantasies of dominating Tosca. In that particular Met production, Scarpia kisses a statue of Mary at the end of the aria and onlookers turn their backs to him in horror. That scene highlights the fact that so many people can share space and engage in the same ritual, but have vastly different experiences. You can trace that seed idea through “Crown Heights”, “The Dark Diary”, my New York Times erasures, and many other poems in the collection.

MC: There are a lot of gasps in your work, Candace, following a narrative that swerves the perspective with just a word or two, that shocks a kind of deep clarity demanding one re-read the poem again. Not to mention poems that intensify with each line, each connection, covering topics as diverse as climate change, corporate subjugations, the power of Blackness, and systemic societal oppressions, without ever becoming a lecture, without every losing the poetic line, such as here in “blackbody”:

“Said another way, the whiteness effect is

warming our planet beyond safety. 91% of Fortune 500 CEOs are white men. Outdoor air

pollution has risen 8% in the past five years. The arctic is melting—the white ice is falling

into the dark sea turning reflective surfaces into heat absorbers. It’s getting warmer. By

“it’s getting warmer,” I mean that in 2010, 10,000 scorched to death in Moscow. By “it’s

getting warmer,” I mean that it was 116º in Portland last summer. By “it’s getting

warmer,” I mean that by 2080, 3,300 will scorch to death each year on New York City

streets, and half of those buried will be Black. It’s getting warmer and I wonder about

white men in boardrooms. I wonder about the PowerPoint presentations and profit

diagrams. On the diagram, the blue line is profit. The Black bodies pile under the blue line over the axis of time and the blue line rises. In the boardroom, the Black body is the ideal—we absorb perfectly.”

How important are these illuminations in your work?

No matter what, my poetry has to reflect the totality of my experience.

CW: I write for my real-time experience of the volta—The moment when my mind makes an unexpected jump or turn because the writing took me there. The poem “blackbody” is very important to me. Textbooks are particularly dangerous, and I wanted to mimic their form to explore the tension inherent in the discipline of science. On one hand, I wanted to acknowledge that the study and practice of science has roots in white supremacy (you could argue that white supremacy could not exist without science, but that’s a conversation for another time). On the other hand, I read scientific papers to learn about the impact of global warming, COVID19, and other issues. The moment where the speaker drops the textbook voice and invokes the “I” to comment on current events was an important moment for me as a thinker and someone who has to navigate the fraught history of science in my own life.

MC: Erasure is a meaningful way of interrogating oppression and control structures, and equally, to my mind, it’s a playful way of destabilizing the sentence, or at least the idea that there is one particular order that results in meaning, or in art. “Panther Gets Loose” is a powerful example and ideally closes out the collection, ending on the lines:

“shouts of laughter, joking mer-

riment and carelessness suddenly changed

into fear and dread

The pantherliberated himself”

MC: After this close, returning back to the beginning of the book, with the prologue “THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF:” (and the duality of the word “property” no less). One is reminded anew of the stakes of identity, of individual power, and of the right to declare one’s own narrative, wherein lies liberation. In that sense, I felt not only another of the gasps that your poems engender, but a deep sense of how you’re claiming that liberation, and that agency, through language.

CW: The most liberating thing I did for myself in this collection is to disrupt the idea that I’m a hero or that my speakers or subjects have to be heroes. I’m deeply flawed, just like everyone else. It’s dangerous for me to acknowledge or speak openly about my flaws because the consequences are especially high. I owe quite a large debt to Morgan Parker for teaching me this idea explicitly and through her work. My poems “On Neoliberalism or: Why My Black Ass Is Tired” and “The Dark Diary” helped me advance my thinking on this issue. In “The Dark Diary”, I write “to tell you the truth / I had been striving / without substance / I couldn’t have been / more disgusted / I had travelled all this way / for the sole purpose / of imagined discourse”. I’m proud of myself for letting myself wonder if the act of writing poetry is as noble as people tend to think it is. “Should I write?”, “When should I write?”, and “Are there times when writing wasn’t the appropriate action?” are all important questions.

There is also a lot of love, joy, and humor in this book. Even my bleakest poems have a bit of humor. One of the reasons why I practice reading my poems quite a bit (and even memorize some of them), is that it’s one of the opportunities I have to acknowledge and express humor. This “reading over” of my joy and humor happens because many of my readers have only thought about the Black, queer, and/or fat experience as a single-dimensional site of trauma. I don’t really feel the need to correct these readers, or shy away from or include more trauma in my writing because of them, but I do think about this often. No matter what, my poetry has to reflect the totality of my experience. Then, I can choose which poems readers have access to and which ones are kept close to my chest.

![[VIDEO] ‘The Winchesters’ Cast Previews ‘Supernatural’ Prequel Spinoff [VIDEO] ‘The Winchesters’ Cast Previews ‘Supernatural’ Prequel Spinoff](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/the-winchesters-video.jpg?w=620)