I have nothing against grandfathers. In fact I love my own, and it was my recent experience of cutting his toenails that prompted this list. My grandfather’s toenails had grown grotesquely long and become a fall risk. As I made attempts to cut them, he kept thanking me. Alternately he mistook me for a doctor, a nurse, and a stranger. What books had I read about this– about caring for grandparents as their bodies and memories become disobedient? Or the flipside: grandparents caring for or raising grandchildren?

As I searched for books spotlighting grandparent-grandchild relationships, nearly all I found were grandmothers. There is something about grandmothers– or perhaps, the figure of the grandmother in our imaginations. Witty and wise, loving and hating, good and evil. Keeper of secrets, stories, and histories. In these books, grandmothers are often portals to places that are gone. To a past time in Turkey, Guadeloupe, or Palestine. Whether they intend to or not, these grandmothers keep those places and times alive.

These books bring together grandmothers and grandchildren. In uniting old and young, one clarified theme is care– the necessity of it in both directions. Who is to care for whom? There can be blurred, shifting boundaries between grandmothers and grandchildren. Across these books, we see the sharp edges of the caregiving work that accompanies dementia, forgotten names, harsh demands, falls, bedsores, death and its aftermath. And we see grandmothers as caregivers who dole out advice, cook elaborate meals, provide stories and other forms of nourishment.

The Summer Book by Tove Jannson, translated by Thomas Teal

In twenty-two vignettes as dreamy as summer, we see the tender and often funny adventures of six-year-old Sophia and her grandmother on a rustic island off of Finland. Sophia’s mother has died, and this grief laces the book as the pair talks (and shouts) about God, death, and angleworms. Grandmother sneaks cigarettes and teaches Sophia how to trespass, “increasing her knowledge of life considerably.” Sophia reminds Grandmother about her medications and retrieves her walking stick when it sinks in water. In one of my favorite vignettes, “The Crooks”, the pair is not invited to a boat party, and find a gift and note reading “Love and kisses to those too old and too young to come to the party.” There is something so poignant about Jannson’s narration, which is equally comfortable with the too old and too young: Grandmother with her stories and weariness, and Sophia with her creativity and searching questions about life.

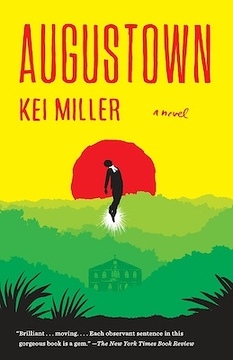

Augustown by Kei Miller

In this novel set in 1982 Jamaica, Ma Taffy is technically six-year-old Kaia’s great-aunt. But as the narration notes: “in this household and to everyone in Augustown, it seems an unnecessary distinction to make.” Ma Taffy is blind, and smells something wrong when Kaia comes home after a teacher has horrifyingly chopped off Kai’s dreadlocks. Sensing disaster, a coming autoclaps, Ma Taffy starts telling her grandson the story of the flying preacherman Bedford. She recounts how he “really did begin to fly. I telling you this because I did see it for myself.” Ma Taffy is a holder of old-time stories, of the history of Augustown. This novel is a capacious portrait of Augustown, with detailed sketches of its people, history, and landscape.

The Bridge of Beyond by Simone Schwarz-Bart, translated by Barbara Bray

This is an epic, beautiful novel! Told from the perspective of an older woman Telumee who is recollecting her life, this novel details five generations of women in the Lougandor family in Guadeloupe. I loved the fluid portrait of Telumee growing up from a child into a woman nearing the end of her life. It is moving how her stories thread her through her family history and back to her great-grandmother Minerva, who lived through slavery and into abolition. I was also moved by the steadfast, central relationship between Telumee and her grandmother Toussine, who raises her. This is a novel steeped in Creole oral tradition, and you can hear Toussine’s voice as clearly as you hear Telumee tell their stories. Toussine–called Queen Without A Name by the community– is full of care, wisdom, and proverbs for her granddaughter, such as: “Behind one pain there is another. Sorrow is a wave without end. But the horse mustn’t ride you, you must ride it.” We see these proverbs become meaningful for Telumee. When working in a white woman’s house, Telumee pictures Queen Without a Name’s smile and hears her proverb, “and that smile would put heart into me, and I would sing as I worked, and when I sang I diluted my pain, chopped it in pieces, and it flowed into the song, and I rode my horse.”

La Bastarda by Trifonia Melibea Obono translated by Lawrence Schimel

Trifonia Melibea Obono’s slim novel is the first by an Equatorial Guinean woman translated into English. In it, we follow Okomo, a young girl living with her strict grandmother and grandfather (who has newly taken a second wife, leading to complex grandparent dynamics all around). Okomo is a “bastarda”– a daughter of an unmarried Fang woman– who wants to find her father (who her grandparents denounce as a “scoundrel”). The novel traces Okomo as she moves from obedience to rebellion, joining the “Indecency Club”, a spiky, self-possessed group of girls who wander deep into the forest to have sex with each other. One girl draws Okomo in, saying: “You don’t need to obey your grandmother, she isn’t here watching your every move. Come on, try it. You’ll like it. You’re in the forest– the Fang forest is a free space. Now you’re free.” I loved following Okomo come of age into her self-identity as a lesbian as she searches for family, identity, and freedom.

Boat Number Five by Monika Kompaníková translated by Janet Livingstone

Here is another cranky, demanding grandma, who refuses that title. “Do I look like a Grandma to you?” she asks, insisting on being called Irena. This novel follows her granddaughter, Jarka, a twelve-year-old left to her own devices in Bratislava. Jarka describes her absent mother (who insists on being called Lucia) and grandmother as such: “They could easily have been two older babysitters. I could just as easily have been living with the neighbors.” Through Jarka’s young eyes, Kompaníková observes the unpleasant realities of Irena’s ageing: liver-spots, wheezing, and uncompromising commands given to Jarka. When Irena dies, Jarka and her mom inherit a garden, where Jarka begins to “live [her] other life.” She abducts twin babies outside a railway station, pushing their carriage to the garden and beginning a precarious life caring for them.

Everywhere You Don’t Belong by Gabriel Bump

This novel is hilarious and so, so tender. It is narrated by a Claude, a young Black boy growing up in South Shore. When his parents leave Chicago, Claude is raised by his grandmother and her perpetually-heartbroken friend Paul. He falls in love with Janice, his classmate at school. After they live through riots in South Shore, Claude decides to leave Chicago for college. I love the tone of this book: irreverently funny and surprising and brimming with love. One of my favorite moments is when– after his parents leave and Claude can’t stop crying– his grandma starts destroying objects. She steps on his dad’s favorite Temptations records, takes a weed whacker to his mom’s remaining clothes, and nearly burns a cardboard cutout of Dennis Rodman until Claude finally intervenes. Later Claude sees Grandma dancing with the cutout, “smiling, eyes closed, far away. That smile I hadn’t seen before. It was pure and light. For me, she was willing to burn her happiness. For her, I stopped crying.”

Rifqa by Mohammed El-Kurd

This poetry collection is named for the poet’s grandmother, Rifqa El-Kurd. The book is dedicated to her and to occupied Sheikh Jarrah in Jerusalem. Rifqa appears and reappears in the collection, bringing in her wit, humor, resilience, memories, and dreams of a free Palestine. I especially loved the poems that portrait Rifqa like “1948/1998” or “The Biggest Punch Line of All Time”, which describes how “Over the years her fingers thinned, veins like vines. Verandas required less wandering and Teta gave up the remote.” In the afterword, Mohammed El-Kurd details this further. He writes how even though Rifqa suffered from dementia and sometimes forgot his name, “her political conviction stuck. The atrocities she witnessed blanketed her subconscious, so much so that, amid her memory’s decay, her stories of the Nakba were still highly detailed, her comments hurled at the TV news coherent and complex.”

The Pachinko Parlor by Elisa Shua Dusapin, translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins

Claire, a Swiss-Korean, is visiting Tokyo and her grandparents, who are Zainichis, members of the Korean community in Japan. While cohabitating with her grandmother – who is forgetting things, getting lost on the train– and her grandfather, who runs a pachinko parlor, Claire meanders through the summer. She tutors a young Japanese girl in French, she plays Monopoly with her grandmother, she probes about the pachinko parlor. And she plans for them to travel to Korea, where her grandparents haven’t returned in over fifty years. As the summer progresses and the trip to Korea looms, Elisa Shua Dupasin explores the complexities of identity, language, home, and family.

The Four Humors by Mina Seçkin

After her father’s death, Sebil travels to Istanbul for a summer to care for her grandmother, who has Parkinson’s. Sebil is to study for the MCAT and make sure her grandmother takes her daily dopamine pills. But as Sebil finds herself plagued by headaches and obsessed with the four humors of ancient medicine, her grandmother becomes the one looking after Sebil. In this patient exploration of care and grief, Mina Seçkin maps Sebil’s webbed relationships to her white American boyfriend who’s accompanied her to Turkey, her grandmother, her dead father, her sister who comes to visit, and a sprawling world of cousins and great-aunts. I loved how family stories crack open inside this book, and how Sebil’s mother and grandmothers become mirrors for each other and the past.