Women get lonely. Men do, too, but there’s something ineffably unique about female loneliness, which is more vulnerable and open to danger than the male version. Female bodies walk through the world as moving targets, rather than as weapons. Perhaps this is why writing on the loneliness of women has a particular haunted quality to it, and on the flip side, more urgency. The search for connection (romantic, platonic, or otherwise) has, for female bodies, higher stakes.

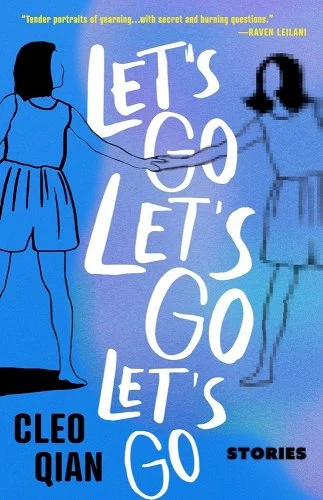

Loneliness and the search for connection are major drivers for the characters of Let’s Go Let’s Go Let’s Go, my short story collection. The young women who weave in and out through my stories lurk watchfully: looking for allies, connection, a meeting of minds that will make them, finally, safe and seen. They are millennials, Internet surfers, queer and questioning, immigrants, the children of immigrants. They wander alone through perilous, defamiliarized urban landscapes.

As I wandered my own landscapes of alienation, loneliness, and fear, the books I turned to showed me the paths of other girls who had walked similar paths. And briefly, while reading them, I did feel less alone.

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang

Jenny Zhang’s groundbreaking short story collection, primarily following Chinese American daughters in Queens, New York, is full of vulgarity, vomit, and wit. The girls and teenagers in the stories grapple with poverty and second languages, and inheritances from parents with failed dreams. They are often shipped off to Shanghai and come home to New York again. From the first piece we are handed painful self-awareness of feeling separate from others (“While I could still improve in either language, my parents could not, they were on a road to nowhere…it was up to me to shine and that scared me because I wanted to stay behind with them, I didn’t want to go any further than they could go.”) as well as brash disdain for others who might feel the same (“She was just a desperately lonely person who needed to be part of someone else’s world.”) Not far underneath the bravado is desperation—raw and unapologetic desperation to be seen, and to not be forgotten.

b, Book, and Me by Kim Sagwa, translated by Sunhee Jeong

This slim and poignant novel follows b and Rang, both outcasts, frequently neglected by their parents, and bullied at school. Though they find support in one another, one accidental slip-up and the fragile connection between them is broken. I loved the hallucinatory, fragmentary prose and painfully-rendered interiority, which captures the scramble, mess, and incoherence of internal pain and a fierce longing to escape. It’s a harrowing and occasionally triggering book, but the slivers of hope feel genuine. The descriptions of the sea and of water throughout this short book are beguiling and convincing. Who among us hasn’t wanted to dissolve into something greater than ourselves?

Cities I’ve Never Lived In by Sara Majka

In 14 glimmering, interconnected short stories—many of which feature the same divorced female narrator—the characters are often going on trips or moving to new places. In one story, the narrator travels from soup kitchen to soup kitchen in different cities, only to find they were “simply the same thing, one after another.”

Majka is excellent at conjuring miniatures, whether describing an exhibit with a display of life-size dolls made by a mentally ill artist, or eating clams and bread from tiny stoneware bowls; and also at rendering complicated, sad feelings that gently punch you in the gut. In my favorite story of the collection, “Saint Andrews Hotel,” a slightly magical realist tale about a boy who leaves an island for the mainland only for his home island to disappear, Majka writes, “I’m happy was the next thought…The unfamiliar recognition of joy, the discomfort in it, the panic. Will it leave me? How to make it not leave me? Thinking that if he pretended it wasn’t there, it wouldn’t leave.”

Winter Love by Han Suyin

It’s definitely not healthy, but the two main characters in this tight novella are certainly looking for connection. The narrator, Red (for her hair), a university student in London in 1944 during the last year of WW2, studying something that requires laboratories and dissections, falls in love with Mara, a fellow classmate and a married woman. Originally published in 1962 and reissued in 2022, it’s a rare depiction of a queer relationship, and not a great model: Their affair is volatile, torrid and damaging – Red’s jealousy and anger, coupled with the flashes of her deep-rooted insecurities and self-awareness made me wince often – and vividly brought to life with the taut, stylish writing. I’m reminded of Louise Glück’s short poem, “Elms,” which begins “All day I tried to distinguish/need from desire” and ends, “[I] have understood it will make no forms but twisted forms.”

Last Words from Montmartre by Qiu Miaojin, translated by Ari Larissa Heinrich

Speaking of queer longing, Last Words from Montmartre—a classic by Taiwanese lesbian iconoclast Qiu Miaojin, and discovered after her death from suicide—almost requires no introduction. These letters, written from Paris, Taipei, and Tokyo and addressed to various characters, describe in intense emotional interiority the love, longing, and betrayals between the unnamed narrator and relationships with two other women in her life. When I first read the book, its earnest intellectualism and the intensity and seriousness with which the narrator dissects her feelings felt young to me, and yet with hindsight I recognize it is a valuable record, and has an honesty that leaves a deep and lasting impression on the reader. When we are young our feelings are that intense, and not all of us survive them.

Intimacies by Katie Kitamura

Katie Kitamura is an expert at subtle affect and building tension under a minimalist surface: sparse sentences, spare plot. Intimacies, following a woman who moves to The Hague to work as a court interpreter during a trial for a prominent war criminal, is laden with the knowledge of separation between self and others that so often creates alienation. This includes her relationship with Aidan, a married man with whom she begins an affair that she suspects can go nowhere. This narrator, however, is more accepting of this alienation than other protagonists on this list—and it is with this clinical detachment and self-awareness of the boundaries between which we can connect to others that the murky, sometimes sinister intimacies of this novel plays out.

If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha

In a slightly more uplifting vein, this enjoyable novel by Frances Cha follows four women connected only by the coincidence of their living in the same apartment building in Seoul. There’s Kyuri, a “room salon girl” who plays escort to wealthy guests and is riddled with debt to plastic surgery; her roommate, Miho, an art student who went to college in the States and is floundering with a hyperwealthy boyfriend far out of her socioeconomic strata; a pregnant housewife, Wonna; and Ara, a mute hairdresser with hidden trauma in her past. The women (or girls) are all desperate and grappling with shame in the patriarchal, capitalist systems keeping them bound. Still, by the end of the novel, Cha pulls off a hopeful ending, with the four girls banding together in a moving moment of support and self-determination.

Nana by Ai Yazawa

Hands up, Ai Yazawa hive! Nana, a Japanese manga series from the early 2000s which influenced the wardrobes of an entire generation of Asian girlies, follows two 20-year old girls both named Nana who move to Tokyo. There’s the chain-smoking, dark-haired, heavily-mascaraed, husky-voiced Nana Osaki, a vocalist for a rock band who leaves behind a tragic past to pursue her music career in Tokyo. Then there’s Nana Komatsu, femme, kitten heels-wearing, naïve and loving and wildly romantic, who moved to the city to pursue a boyfriend. After a chance encounter, the two Nanas move in together, and what results—over 21 volumes of manga, and remakes in anime and live action films—is a bittersweet story of attachment wounds and self-destruction and bad choices with men, but also the deepest love and loyalty between these two women. Every day I pray the hiatus will end and Ai Yazawa will finish it. Also, if Nana and Nana aren’t in love then I don’t know what queer longing is.

The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner

In 1975, an ingénue art student (nicknamed Reno, because guess where she’s from?) with an interest in Land Art moves to New York, where she falls in with a group of rich visual artists and embarks on art projects of her own, including racing (and ultimately crashing) a motorcycle across the Bonneville Salt Flats to trace a line. Reno is kind of an Ur-type of a Cool Art Girl, with her encyclopedic knowledge, physical bravery, and seemingly unconscious ability to attract older, successful artist men who mentor her. Her life in New York is both grubby and glamorous beyond dreams, at least for people her age today. But that doesn’t stop the desires that bring Reno to New York or the loneliness and alienation which she describes after getting there—as well as her desire for incident, for encounter—from being compelling and hyper stylishly-written to boot.