Though they’ve been icons of cinema for a while—see: Sadako, Shutter—it’s taken English literature a little longer to catch up to Asian women front and centre in stories of ghosts and horror.

The prevalence of female ghosts across Asia has always interested me: how often their origin is rooted in concepts of failed femininity and spoiled maternity; how they simultaneously embody marginalisation, fearsome empowerment, and freedom from restrictive gender norms. Multiple female artists in Singapore and Malaysia, for example, have resonated with complex and sympathetic takes on the vampiric pontianak.

On the flipside, the marginality of living women in both Asia and diaspora has produced social works and ingrained trauma in which darkness begins from systemic roots. More often than not, female Asian horror is explicitly intersectional, especially from the dimension of queer writers.

In my novel The Dark We Know, Chinese American art student Isadora Chang returns to her secluded hometown in the mountains for the funeral of her abusive father. But her return forces her to reckon with everything she’s been holding at bay: her tense relationship with her silent, cooped-up mother and their haunted house; the sudden suicides of two of her friends and the reunion with the third friend that she left behind; the religious community she removed herself from; the nightmarish drawings she doesn’t remember making, and a supernatural entity that takes the town’s children. Still, it’s a novel about healing as much as haunting, and demanding the right to survive.

These are some books about haunted Asian girls and women. There are ghosts and terrible visions in the literal sense, but hauntings underlie spectres of other kinds: violent patriarchy, colonialism, racism, fraught families, grief, and unresolved injustices. After all, these things create ghosts in themselves.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

In Han Kang’s Booker-winning novel, a Korean woman is so possessed by nightmares of butchery that she disavows eating meat and aspires to become more ‘plant-like’—a decision that puts her at increasingly violent odds with the patriarchal, tightly conformist social mores around her. A dark, surreal book about carnivorism, patriarchy, abuse, and female autonomy, The Vegetarian is a book my mind goes back to time and time again.

She is A Haunting by Trang Thanh Tran

Closeted bisexual Jade Nguyen reluctantly heads to Vietnam for the first time to spend the summer with her estranged father and the old French manor he’s renovating into a bed-and-breakfast. But though the manor is verdant and seemingly idyllic, Jade’s relationship with her father and Vietnam are fraught. There’s a beautiful, wickedly sharp girl she’s starting to fall for. A ghost bride is telling her not to eat, and the Flower House is haunted by colonial histories and bloodshed that stain it far beyond the Nguyens’ family troubles. The desires of the house, the ghosts, and Jade herself are lush and hungry.

The Manor of Dreams by Christina Li

In another sapphic gothic, the daughters of a trailblazing Chinese Hollywood starlet gather ather sprawling mansion for the reading of her will, only for another estranged family to be gifted the inheritance. However, both families soon find that the manor is also inhabited by something else entirely. Told in dual timelines and spanning three generations, Li’s tense and dreamy adult debut follows roots through toxic ambition, grief, and the curse of the American Dream.

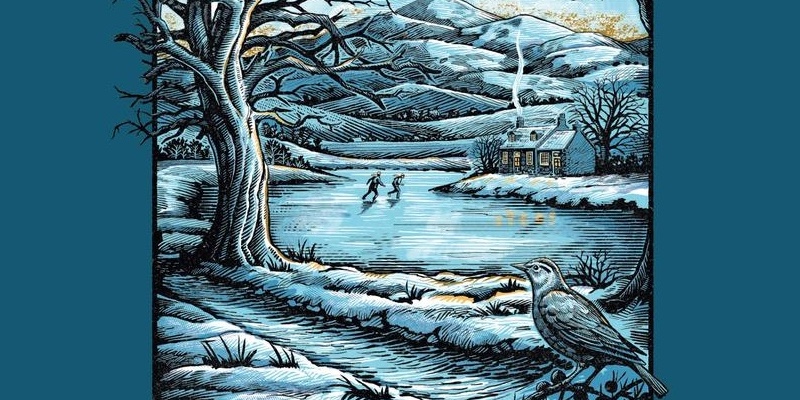

How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C. Pam Zhang

When their abusive father dies in the age of the Wild West, leaving them penniless orphans, two young Chinese sisters set out with his body on a horse and journey through the frontier searching for a place to bury him. The book itself reads like traveling a strange, inhospitable expanse studded with skeletons and stories of tigers and dragons. An immigrant family tragedy in the dust of the Gold Rush; How Much of These Hills Is Gold is a less traditional haunting, but haunted nonetheless.

Black Water Sister by Zen Cho

Malaysian American Jess goes back to her grandmother’s home in Penang, accompanied by the ghost of her grandmother both questioning her about being a lesbian and sending her on a quest to settle a score. Unfortunately, Ah Ma had her own baggage: she was the medium of a vengeful deity called the Black Water Sister, who now has her eyes on Jess. The book enters the uniquely Malaysian Chinese world of gods, ghosts, gangs, and family. Cho’s work is always fantastical, witty, and heartfelt, even with the edge of darkness; as a Singaporean, this was a haunting of the home kind.

The Hysterical Girls of St. Bernadette’s by Hanna Alkaf

Another Malaysian novel, in which an elite all-girls’ boarding school is struck with a sudden wave of screaming hysteria. Two girls find themselves digging into the school’s history searching for the truth, unaware that something still lurks in the darkness. Alkaf explores mental health, trauma, healing, and the image of a school of perfect girls that isn’t so perfect anymore.

The Forest of Stolen Girls by June Hur

A richly atmospheric historical mystery in Jeju Island, Korea: Hwani returns to her home village to investigate the disappearance of her father in the forest that has also taken thirteen pretty girls, and where Hwani and her sister were once found near a dead body. There are whispers of a man in a white mask in the trees, and Hwani and her estranged shaman sister will need to uncover buried memories in order to find the truth.

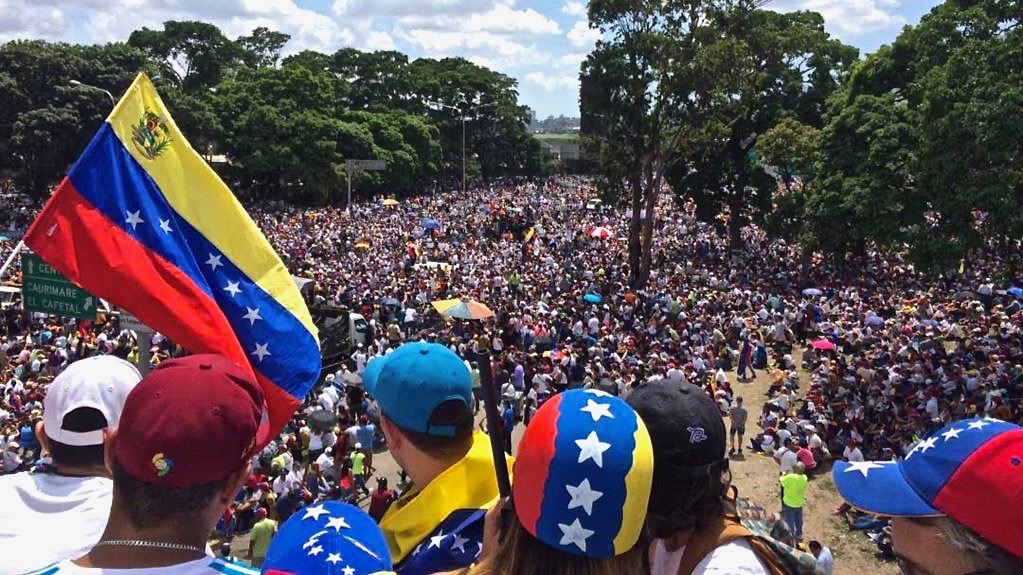

Bat Eater and Other Names for Cora Zeng by Kylie Lee Baker

It’s Hungry Ghost Month, and the gates to hell are open in New York’s Chinatown. Crime scene cleaner Cora Zeng is already traumatised by the murder of her sister, who was pushed in front of a train by a man shouting bat eater. She’s also haunted by inexplicable bite marks, germs, strangers’ hands, and the bat carcasses she keeps finding at crime scenes–murder scenes of East Asian women. With her debut horror, Lee Baker takes a subversive and reckoning knife to anti-Asian violence in America.

The Eyes Are The Best Part by Monika Kim

In Monika Kim’s debut, a Korean American college student becomes obsessed with eyes. Specifically, blue eyes. She sees them in her dreams. She sees them around campus. She sees them in the head of her mother’s horrible new Asian-fever white boyfriend, and imagines how they would crunch between her teeth. Cannibalism and coming-of-age cross sharply and deliciously with themes of sexism and fetishisation. In this one, she’s the killer.