My first semester in graduate school for my MFA in poetry, I locked myself in my room in the apartment I shared with five roommates in the Lower Haight in San Francisco to write a paper about Robert Lowell’s Life Studies, the book widely considered to kick off the confessional movement in American poetry. I still have the Robert Lowell paper saved deep in a folder within a folder on my hard drive, and I pull it up to see what 23-year-old me had to say about the confessional. Here’s part of my thesis: “While it is certainly true that Lowell’s autobiographical writing in Life Studies has greatly influenced some escapist, arbitrary, and amateur confessional writing, Life Studies itself is filled with much more than arbitrary detail, and extends far beyond escapist writing.” Escapist, arbitrary, amateur. This list of words used to deride and dismiss the confessional—to which my present-day self would add, self-indulgent, overly emotional, hysterical—strike me now as very gendered. It’s interesting to me that I—a self-proclaimed feminist then and now—was using the poetry of a white cis man to argue that a poetic mode primarily associated with young women’s writing—and one that I used in my own grad school poems about female friendship, music, lip gloss, walking around in the mall in the 1990s—can indeed be valid, powerful, and even political. By arguing that Lowell’s personal poems were in fact astute social commentary, was I also arguing this same case for my own?

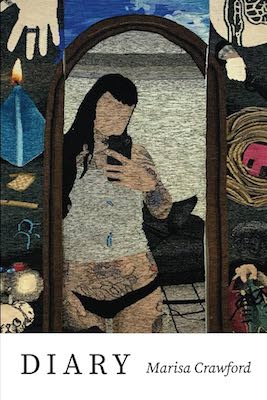

Life Studies may have been one of the first books to introduce confessionalism into American poetry, but the term confessional is most often linked with Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and other women poets whose writing is too commonly misread and dismissed as autobiographical gushings of emotion rather than crafted, intentional social commentary. My new book of poems, DIARY, interrogates these ideas about the confessional and gender. Rather than engaging in the acrobatics of trying to come across as not too emotional, not too messy, not too personal; always measured and buttoned up and chill and universal, the poems in my book indulge in the mundane, the feminine, the bratty and sad and bodily and TMI. I’m so excited and inspired by other contemporary writing by women and gender-fluid poets who push back on antiquated and sexist ideas around the confessional by doing the same. Here’s a list of 8 books in this vein:

Gravitas by Amy Berkowitz

Speaking of graduate school, this necessary book digs into “the tendency of MFA programs to teach women that their lives aren’t worth writing about.” These crafted, conversational poems insist on the power and merit of everyday speech in women’s writing, referencing the free-wheeling poetics of both Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems and Paule Marshall’s “From the Poets in the Kitchen.” Gravitas interrogates an academic space that closes its eyes to a serial abuser professor on staff while chronically dismissing poems about the everyday by women: “Believing that poetry about the life of a young woman lacks gravitas / believing that the life of a young woman lacks gravitas / enables a certain cognitive dissonance.”

The Gone Thing by Monica Mcclure

The followup to McClure’s 2015 book Tender Data, The Gone Thing explores family history, class mobility, labor, and loss in elegant, unflinching poems. One of my favorite things about Monica’s work is how her speaker fucks with us, calls the reader to task, and plays with our assumptions: “Yes I am talking about being poor in America / Suck my dick I am no longer poor I’m high-salaried”. Pastoral beauty and designer perfume mixes with despair, disgust, filth, and astute commentary on systemic oppression, work and labor.

mahogany by erica lewis

Written during the years when the author cared for her mother at the end of her life and after her mother’s death, mahogany subverts conventional narratives around grief and the confessional with haunting poems about family, loss, and the struggle to make it through each day. Lewis weaves pop culture, politics, contemporary and historical literature into poems that draw their titles and inspiration from songs by Diana Ross and The Supremes or Ross’s solo career: “my mother used to clean houses / as a child / some days I can barely / get out of bed /in my mind / she’s like diana ross / scrubbing the white lady’s stairs / in lady sings the blues / except prettier / and with green eyes”

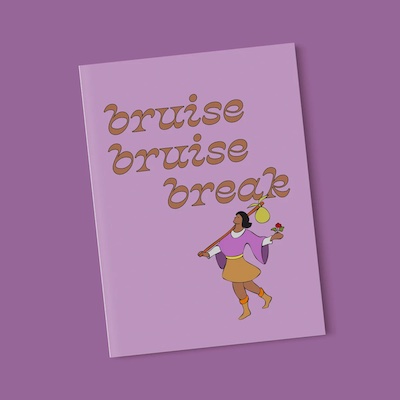

Bruise/bruise/break by Jennif(f)er Tamayo

Printed in vibrant full color and blending poetry, prose, photography, and other visual elements, Tamayo’s radical book connects the dots between cycles and systems of violence in U.S. history—from the genocide of native people that the country was built on to the American poetry world’s colonialist roots. Interspersed with images of U.S. immigration forms doctored to tell the poet’s own family story, bruise/bruise/break digs into familial and global histories while blasting open conventions around genre, grammar, gender and respectability.

Bedroom Vowel by Zoe Tuck

Zoe Tuck’s poems break the fourth wall, inviting in talk about everything from work and money to friends and even commentary on the poems themselves: “I’m sick of the I / I wish I could just write about mythological and historical themes”. Accounts of everyday life—cooking dinner on a phone call with a friend, planning how to make “like $1,000 this month,” staying up late watching Encino Man—are balanced with reflections on the French Renaissance, tarot, Ancient Greece, Hannah Arendt, The Odyssey, The X-Files, “The Thong Song.” The result is a constellation of references that builds on itself into the size of a whole life.

Killing Kanoko by Hiromi Itō, translated by Jeffrey Angles

Groundbreaking Japanese poet Hiromi Itō has been writing about feminist issues surrounding sexuality, reproduction and the body since the early 1980s. Turning away from the formal poetic conventions of the era, her poetry uses colloquial, sometimes childlike and vulgar language which brought to her being considered a “shamanness” pulling her language “from some mysterious source deep within.” In Killing Kanoko, originally published in 1980 and translated in 2009, Itō writes about childbirth, menopause, abortion, and ambivalence around motherhood in ways that still feel very much taboo even today.

Dark Beds by Diana Whitney

Diana Whitney’s quietly explosive collection of poems explores womanhood, motherhood, grief, the spaces where being the parent of a girl child and being a woman overlap with scars left over from childhood. There’s “danger everywhere” in these moody, atmospheric poems that bring a modern, feminist spin to the pastoral as they conjure the natural world, dark skies, early morning gardens and frozen rivers. Time passes and everything grows so fast and also in slow motion—chickens, lilacs, girls, relationships strained by the years. As Whitney’s poem “The Long Goodbye” asks, “How can you savor what you have / when it demands so much attention?”

What You Refuse to Remember by MT Vallarta

This book’s speaker tells us, “I once wrote on a fellowship application that I write poetry because it is the only way I can scream. I didn’t get the fellowship.” This is just one example of how these powerful poems exploring queer Filipinx identity, trauma, immigration, colonization, and art call into question the rules of academia and the so-called rational world. In a white supremacist patriarchal culture where science and logic are so often privileged over the spiritual, emotional, and intangible, these poems insist the full spectrum of humanity has a right to exist, thrive, and be taken seriously.