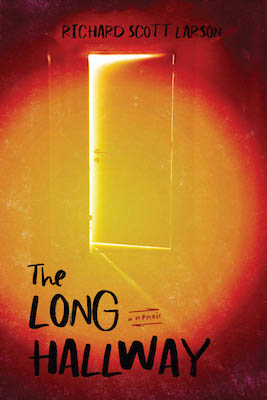

Horror has always been deeply personal to me. Our obsessions can often come to structure and shape our inner lives while at the same time rendering the most intimate parts of ourselves illegible to those who don’t share them, and my love of horror as a child was a kind of closet where I could hide before I understood that I was already living in one as a queer boy who wanted nothing more than to the conceal desires I believed marked me as a monster. My memoir, The Long Hallway, uses the language of horror to construct a critical frame around my coming-of-age and family story. The familiarity of the genre becomes a narrative scaffolding that brings with it a universal vocabulary to describe experiences of isolation, fear, hopelessness, and shame, which to a closeted kid are the ingredients of a daily life in which survival is the only imperative.

I watched John Carpenter’s Halloween relentlessly as a child during the years in which my family broke apart while father succumbed to alcoholism and I faced my own demons in front of the television screen, and I realized later that I inadvertently allowed the film’s characters and events to become a guide for how to understand the world, as well as what my own place in it would ultimately be. The memoir that emerges from my misguided queer education—through my identification with a masked, knife-wielding villain chasing down hyper-sexualized teenagers—grafts scenes of personal experience onto the structure of Halloween, and thus allows the genre conventions of horror to say out loud and more clearly what I couldn’t when I was learning and reckoning with these unwanted truths about myself.

I’ve encountered various other personal stories told through the lens of horror, either before or during the construction of my own, and I now understand more deeply how the genre can both inflect and infect our experiences of the world, especially as queer and marginalized writers attempting to universalize an experience that we once believed only we could ever understand. Horror gives us a lineage of tropes and terminology with which to describe the things that haunt and frighten us—the things we dread the most—which so often reflect elements of our personal histories back to us, metaphorically or otherwise. And these are some of the books that helped me understand how writing about horror can be a way of writing about ourselves.

Night Mother: A Personal and Cultural History of The Exorcist by Marlena Williams

Night Mother offers exactly what its subtitle suggests, as this memoir-in-essays serves up a blend of memoir, criticism, and reported history regarding the original production and reception of The Exorcist in popular culture as Marlena Williams explores complex ideas regarding faith, family, sexuality, womanhood, and grief. “The Exorcist, when you really get down to it,” Williams writes, “is just a story about a mother and a daughter.” The personal obsession at the book’s core is her relationship with her own mother before and after the latter’s death from cancer, as well as how the two women’s powerful responses to William Friedkin’s iconic film connected and bonded them forever. Horror works here as a shared experience and collective memory giving voice to distinct fears and preoccupations, and the film functions now for Williams as a family heirloom of sorts, a site of reckoning with the past as she forges a future without her mother to guide her.

This Young Monster by Charlie Fox

As a young writer raised on the iconography of genre films and having formed a worldview based on imaginary worlds that reflect our own in sometimes frightening or shocking ways, Charlie Fox’s essays diagnose a history of queerness and monstrosity: “Being bad in art, stimulating outrage or horror, is just another way of behaving monstrously (cathartic? Oh yes!) and a role to live up to when society proclaims your desires to be ‘sinful.’” Fox’s voice is mostly critical and intellectual until it suddenly isn’t, and the way he portrays his younger self learning about the world through popular culture is striking evidence for his broader claims. “Self-Portrait of a Werewolf” takes the form of a letter written to the titular monstrous shape-shifter and interrogates Fox’s early obsession with the archetype, directly asking probing questions about its expansive influence on the world beyond the screen: “I’m through with thinking of the monster as a wholly negative role, which is your curse, since you live in wait for a love that will probably never arrive.” There’s a restless and brilliant mind at work in these pages that brings the world of the popular imagination alive in completely new ways.

Night Rooms: Essays by Gina Nutt

Gina Nutt’s Night Rooms is an exquisite essay collection that centers the idea of escape as a presiding principle, not just in form—as these essays break from conventional expectations in provocative ways—but also in content. In these pages, the grounding conventions of horror films serve as handholds as the narratives circle around themes of the body and grief and survival. All the while, something sinister lurks in the white space between the paragraphs, an unnamed threat that’s felt rather than seen. Nutt orbits traumatic personal experiences, including family deaths by suicide, with a poetic reliance on imagery and suggestion to convey the reality of her life’s shocks and their reverberations. Horror becomes a telling touchstone to link these essays together, because what is horror if not the deliberate recasting of our greatest fears and traumas into entertainment, making something meaningful from what is otherwise just darkness?

Ghostland: In Search of a Haunted Country by Edward Parnell

Film and literature of the ghostly and supernatural can evoke other reckonings beyond those based on identity and belonging, as Edward Parnell demonstrates in Ghostland, a deeply moving meditation on grief and loss. In the context of revisiting the horror stories that had once perhaps incongruously provided him with a kind of comfort in his youth, he now asks them to do the same for his haunted adulthood. Deceptively a survey of canonical horror stories that have been meaningful to him over time, the book’s autobiographical elements ultimately provide a deeper and incredibly heartbreaking relationship with what the ghost story really is: a visitation from the past that can never again be made flesh, and in this case also a reminder of devastating personal losses that can come to define us for as long as we remain among the living.

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

“The memoir is, at its core, an act of resurrection,” writes Machado in the opening pages of In the Dream House, an innovative account of her experience of domestic abuse that embeds her personal story within an extensive cultural history. The book is structured as a series of brief sections titled after various tropes—many of them from horror film iconography, such as “Dream House as Creature Feature,” “Dream House as Haunted Mansion,” “Dream House as Demonic Possession,” “Dream House as Apocalypse,” and “Dream House as Nightmare on Elm Street”—expressing elements of her time in a house in Indiana where her girlfriend lived during most of the duration of their relationship while Machado was a graduate student in Iowa. Her story is punctuated by harrowing moments of conflict that feel, because of their specificity, almost uncannily familiar. Readers come to inhabit her mind so wholly that the claustrophobia of her relationship with this other woman is made present first in the mind and then in the body, a cancer spreading quietly beneath the skin.

With Bloom Upon Them and Also With Blood by Justin Phillip Reed

Much is made of the “poet’s novel,” a genre in which prominent poets bring their careful lyricism to book-length fictional prose and inevitably reach a broader audience while also attending faithfully and fervently to the rigor of their craft. But there should perhaps be more attention given to the poet’s essay(s) as well. Justin Phillip Reed has been widely celebrated for his experimental body of poetry that centers its speaker’s urgency and frequent rage about white supremacy, the suppression of queer sexuality, the trap of masculinity, and the politics of Blackness in America, and the essays collected here orbit similar concerns in the context of popular horror films. “What is it I want from horror?” Reed asks. “What does it want with me? What is it?” And he proceeds to both answer and deepen these questions by interrogating images from popular horror films against their cultural origins—Drew Barrymore’s lynched body dangling from a tree is one striking example—and ultimately concludes with another question: “What if horror is not yet for Black people?”

Lunar Park by Bret Easton Ellis

Hear me out: I know this is a novel, but the fact that Ellis superimposes a horror narrative onto a mock memoir—in which the author channels his own real-life career and hedonistic excess into a (non-auto)fictional exploration of his earlier body of work literally coming back to haunt him as he enters middle age—speaks volumes about the genre’s capacity to reframe lived experience into a terrifying odyssey toward self-recognition, and perhaps a kind of peace. In the novel, the character of Bret Easton Ellis attempts to reconnect with a former lover and the son they share together, and in doing so launches himself into a bizarre and frightening world that is perhaps, in the end, one of his own making, as his fictional creations seem to come to life. Ellis is an expert in the language of violence, especially when it crosses the line between the real and the unreal, the remembered or the dreamed—even as it’s always somehow personal.

It Came From the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror, edited by Joe Vallese

My essay on John Carpenter’s Halloween that first explored ideas later developed in my memoir (and which originally appeared here in Electric Literature) is anthologized in this wide-ranging collection of essays that feature queer writers reflecting on canonical horror films and how they informed or expanded their understandings of variously defined identities. The formula of juxtaposing personal narrative with non-scholarly film analysis offers readers new perspectives on popular subgenres that we might have thought we already understood, the queer experience being one that necessarily refracts and reshapes our conceptions of the world. As editor Joe Vallese writes in his introduction, “These essays don’t draw easy lines between horror and queerness but rather convey a rich reciprocity, complicating and questioning as much as they clarify.” Carmen Maria Machado on Jennifer’s Body is essential reading, but the collection as a whole gathers strength as it moves through the canon and shows us all the possibilities of identification and longing that we may have missed on those first viewings in the dark basements of our childhoods, always looking for something of ourselves in what we saw on screen.

![Watch ‘911’ Season 6 Episode 9: Bobby’s Sponsor Wendell Scene [VIDEO] Watch ‘911’ Season 6 Episode 9: Bobby’s Sponsor Wendell Scene [VIDEO]](https://tvline.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/911-season-6-episode-9-bobby-video.jpg?w=620)