Sure, graphic novels and memoirs are the latest literary rage, but have you heard about graphic poetry? Many contemporary women poets are reimagining the relationship between text and image, offering new ways of representing women’s bodies, and cutting and erasing found texts like they’re slicing up the patriarchy itself. And in many ways, they are. Their graphic poems often reconstitute source texts by men, which they delight in erasing and rewriting. Each visual and textual utterance is a powerful reclamation of self, voice, body, and history.

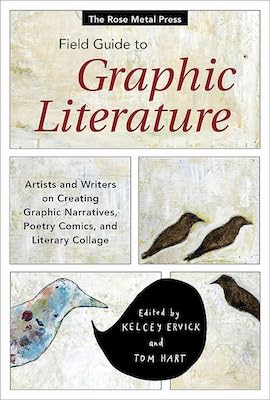

In my introduction to the Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Graphic Literature, which I co-edited with Tom Hart, I chart a longer-than-might-be-expected history of graphic literature that is, alas, just as male-dominated as one might expect. Beginning in ancient Egypt, I suggest a literary lineage that includes medieval Japanese Emaki, Mayan codices, William Blake’s late 18th-century “illuminated printing,” and the early 20th-century concrete poems of Guillaume Apollinaire. In other words, mostly men.

Perhaps that’s why the work of these 8 graphic poets speaks to me so powerfully. They are speaking for generations of silenced women—and they are angry.

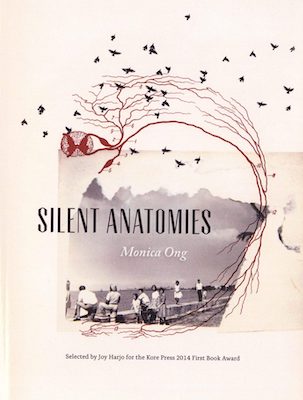

Silent Anatomies by Monica Ong

This powerful collection includes digital collages of anatomical drawings, X-rays, photos, and ultrasounds, but I especially love the vintage medicine bottles on which Ong created labels with various riffs on “instructions for use,” each cheekily labeled “Ancient Chinese Secret.”

The first poem, “The Glass Larynx,” conjures the power of voice with its opening lines, “lips part/disrupt” adjacent to an anatomical illustration of a larynx. The next poem, “Bo Kusho,” which translates to “without luck,” refers to the speaker’s grandfather’s shame at “the fact of five daughters.” On the facing page is a photo of Ong’s mother with her siblings: her mother is disguised as one of the brothers: “The terror of asymmetry. This shortage of sons.”

Her Read by Jennifer Sperry Steinorth

In 1931, English art critic Herbert Read published the first edition of The Meaning of Art, described on its jacket as “a compact survey of the world’s art.” What was notable to contemporary poet Jennifer Sperry Steinorth was that Read didn’t include a single woman artist in his survey. “P l e a s e,” says the speaker who transforms Herbert Read’s text into Her Read: “let/us!/re/fashion/the story.” Steinorth does just that by taking ink, paint, knife, and sewing needle to Read’s original text, creating a triumphant response, not only for the current generation but for all women. Over a reproduction of Salvador Dali’s Persistence of Memory, the speaker invites us to “dig deep and sing our great great/great great great great great great/great great/Grand Mothers’ blues.”

Hotel Almighty by S. Jane Sloat

More in the spirit of play than protest, S. Jane Sloat creates poetry from prose, reconstituting the words and world of Stephen King’s Misery. Sloat finds dreamy delight in King’s suspenseful tale: “In an act of imagination/late at night./He threw back his head and/a variety of strange and poisonous flowers grew.” These lines feel like they speak to the creative process in general and to this book in particular. Each page is a poem revealed through erasure, strange word-flowers growing up from crayons, collage fragments, and loose threads that suggest a feminine hand.

In Between by Mita Mahato

Mita Mahato’s delicate cut-paper collages captivate the eye while communicating anger and grief: at the loss of her mother, at the loss of animal species, at the election of Donald Trump. Mahato’s main medium is newsprint, ephemeral and disposable by design, from which she creates elegiac poetry in surprising silhouettes. In “The Extinction Limericks” Mahato transforms the bouncy and bawdy refrain of limericks into a lament of loss: “There once was a tiger from Java.” The rest of the “limerick” is missing; only the silhouette of an extinct tiger remains. The book ends in anger and fear as a new President takes office. The red stripes of the American flag twist and turn over news photos amid hand-lettered lines of the “Star Spangled Banner”: “Oh say can you see?/Oh say can you see.”

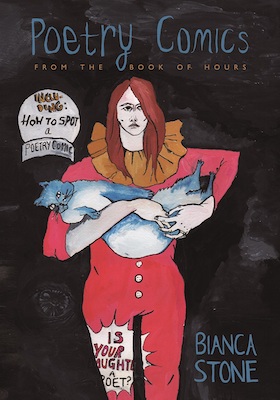

Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours by Bianca Stone

Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours is filled with inky drawings of women’s bodies—in houses, as houses, with houses as heads, and without heads. “For my ladies,” Stone writes in an unsteady cursive, “whose beauty and sorrow are great.” In Stone’s poetry comics, lines of her own poetry now appear in speech bubbles attached to various characters, animals, and inanimate objects, disrupting the notion of a poem’s “speaker” and the fluidity of identity.

Hollywood Forever by Harmony Holiday

Reading Harmony Holiday’s Hollywood Forever is like watching a heady documentary of Black history while a poet stands in front of the television reciting her poems. The background and foreground texts compete with and complement one another in a transformational sensory experience. The speaker asks herself, as if she is asking someone else: “In what ways did watching your/black father beat your white mother empower you as a brown baby?” But the lines of the poem are almost indistinguishable from the text of the front page of the The Atlanta Constitution, digitally collaged in the background, with its headline article: “Dr. King Shot, Dies in Memphis; Curfew On, 4,000 Guards Called.” On the lower half of the page, where the speaker says of her birth, “I arrived as a kind of vengeance,” the words are written over the face of a smiling woman in an ad for Nadinola, a skin lightening cream. Throughout the book, violence against women is intertwined with violence against Black people in a white supremacist America where—in a notice from the Citizens’ Council of New Orleans that appears repeatedly—“Negro Music” is blamed for “undermining the morals of our white youth in America.”

Glyph by Naoko Fujimoto

In a powerful affirmation of herself as an artist and a reclamation of her roots, Naoko Fujimoto uses her own poetry as source material and takes inspiration from the Japanese tradition of Emaki (picture scrolls) to create an entirely new form of graphic poetry. Fujimoto grew up in Nagoya, Japan where she often visited the Tokugawa Art Museum to see the 11th-century picture scrolls of the Tale of Genji. As a poet living in the U.S., and she composes poetry in a combination of English and Japanese, writing toward an English version for publication. In Glyph, she translates and transforms her poems once again, choosing key lines and combining them with collage and illustrations. The larger format of the book reflects the original oversized 16” x 20” graphic poems. Fujimoto writes that her work is trans-sensory, and indeed it feels like multiple senses are experiencing her kinetic poems, like the tactile collage of a towel fragment turned into an upside-down American flag, representing a towel her grandfather was given to wipe his face after the atomic bomb was dropped in Hiroshima.

Likeness by Katrina Roberts

Katrina Roberts’ Likeness is an ekphrastic search for self—“Mother, daughter, beyond gen-der”—beyond language. “No/words,” begins the prologue of Likeness, which is written in the shape of a house made of words. The book’s poems are composed, not of words, but of images; the poetic “lines” are drawn not written. Many images are “after” famous works of art by men, figures whose heads are replaced with kitchen utensils, weapons, and rainbows. Speech bubbles are filled with signs, signifiers, and scribbles, suggesting the limits of language.

Book of No Ledge by Nance Van Winkel

Nance Van Winkel’s Book of No Ledge is an erasure of the knowledge imparted by the set of encyclopedias her family purchased when she was thirteen. As she explains in her introduction, each page featured “Mr. Explainer,” providing information about such things as “The World” and “Dinosaurs.” Decades later, Van Winkel is “a much older woman” with “X-acto blades,” and Mr. Explainer begs her not to “chop away that whole paragraph about the wonderful westward expansion and put some poem in its place.” But she does it anyway, hilariously, poignantly.