Venezuela, my home country, was once one of the richest countries in Latin America due to the discovery of oil at the start of the last century. Today, Venezuela is in political and economic turmoil with a mass exodus of more than 7 million.

As I wrote my new memoir, Motherland about the fragile concept of home and my complicated relationship to my family and to Venezuela, there were several books that took me back on a quest to understand where we came from as a country. The horrific conditions in Venezuela over the last several years sometimes made us forget what happened before Hugo Chávez.

The list that follows includes some of the essential books about Venezuela. These are not only for people who may know little about the country, but also for Venezuelans who are interested in our past and how, after decades of abundance, we got to where we are today, where families are dismantled and millions of people leave the country in search of a better life.

The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela by Fernando Coronil

Taking some inspiration from Venezuelan playwright José Ignacio Cabrujas and his analysis of the providential quality of the State and the social impact of the sudden wealth that oil brought to the country, Coronil, an anthropologist, addresses the transformation of the Venezuelan State in the last century as the country became an oil nation. From the dictatorship of Juan Vicente Gómez to democracy, marked by the spectacular first presidency of Carlos Andrés Pérez (1974-1979), Coronil explains the relationship of Venezuelans to the State and its presidents. I first read this book when Chávez, thanks to a new oil boom, magnified and personified the notion of a generous and almighty State. It was no longer the State, now it was Chávez. That is why this book, first published in 1997, was also prophetic. Overall, it is key to understanding the Venezuela that preceded Hugo Chávez’s “revolution.”

Things Are Never So Bad That They Can’t Get Worse: Inside the Collapse of Venezuela by William Neuman

William Neuman understands Venezuela as few outsiders do and opens a window into the country with this exceptional compilation of stories. Neuman, who arrived in Caracas to work as a correspondent for The New York Times in 2012, shortly before Chávez died, gathers testimonies and anecdotes that allow readers to understand the social complexities of a divided nation. One of this book’s great contributions is that its characters are those who live and suffer in the country, and the wealth of perspectives Neuman presents is only possible thanks to the years he spent traveling throughout Venezuela.

Comandante: Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela by Rory Carroll

While working as The Guardian’s correspondent in Caracas, Rory Carroll was once the target of one of Hugo Chávez’s typical verbal attacks during his weekly Sunday television program. In this book, Carroll shows the seams of the political project of the man who ruled Venezuela for more than a decade under an eternal promise of utopia that never materialized. In a series of vignettes, Carroll incorporates interviews with people in the presidential entourage and figures who influenced the definition of the so-called “Socialism of the 21st century.”

Bolivar: American Liberator by Marie Arana

Simon Bolivar is similar to a founding father for us. We hear about him almost from the time we learn to read, and there is no shortage of literature about him. However, Marie Arana’s biography excels in capturing the intensity of the Liberator’s dramatic life and does it in an almost cinematic portrayal that matches the grandeur of the man who waged countless wars against Spanish rule to liberate what is today the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and Bolivia. Arana also brings in the forces and influences that shaped Bolivar and expands on his ideas about politics, race and government in a narrative that transpires passion, but without caricaturing or mythologizing him, a frequent practice in Venezuelan politics. Bolivar has been quoted by countless regional leaders, but Hugo Chavez, who claimed to be his spiritual heir, took the fanfare to another extreme. Chavez, who drew parallels between himself and the Liberator and nurtured conspiracy theories of assassination attempts, went so far as to order a national broadcast of the exhumation of Bolivar’s remains by a team of professional investigators to determine whether the father of the nation had been assassinated. The conclusion is that he was not, nor would Chávez be.

Barrio Rising: Urban Popular Politics and the Making of Modern Venezuela by Alejandro Velasco

This book offers a different perspective because it approaches political transformations in Venezuela from an urban and popular point of view. “Over the years, Venezuelans – more and more concentrated in urban spaces – developed an expansive understanding of democracy that combined institutional and noninstitutional, formal and informal, legal and illegal practices in their dealings with the state,” writes Velasco. Barrio Rising reviews the decades leading up to Chávez’s arrival, describes how the concept of democracy was shaped in the working class and how years of exclusion impacted the notion of democracy. It focuses specifically on the changes experienced in the neighborhood 23 de enero, or January 23. Designed as part of the dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez’s ideal of modernity, this barrio became a symbol of democracy when the military was overthrown in 1958. Decades later, when democracy was teetering, the neighborhood became a bastion of resistance. Close to the government palace, its symbolism is such that it was in this neighborhood where Hugo Chávez voted in every election. The ballot became a popular televised show, with hundreds of people cheering for the president, who never lived there but was received with devotion as one of their own.

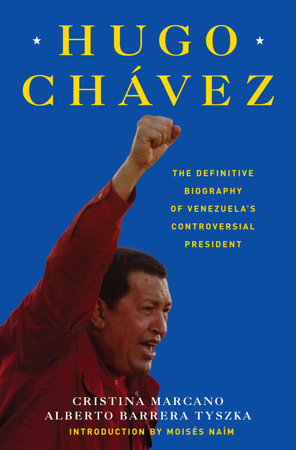

Hugo Chávez by Cristina Marcano and Alberto Barrera Tyszka

Much has been written about Hugo Chavez, the charismatic leader who first appeared on the scene in 1992 when he assumed the leadership of a failed coup d’état in Caracas. But one of the first efforts to portray the man behind the myth was this biography written by Cristina Marcano and Alberto Barrera Tyszka during Chavez’s first term, just when his popularity continued to rise, and he became a divisive and polarizing figure. Marcano and Barrera Tyszka assembled a personal and intimate portrait of the President by interviewing people who were very close to him during his childhood and early years in the Army and by using Chavez’s valuable personal diary. The biography discusses his influences, his family relationships, and how his political ideals were shaped.

Iphigenia by Teresa de la Parra

Not many Venezuelan novels have been translated into English, but one of them is Iphigenia, which caused a stir when it was published in 1924 for giving a dissonant voice to a young woman who tries to rebel against the local machista elite into which she was born. It is the most famous work of Teresa de la Parra, a Venezuelan writer who, despite spending most of her life outside the country, focuses part of her work on portraying the Caracas society of the early 20th century. Iphigenia is notable for addressing the non-conformity of a woman and the veiled criticism of the elite.

Doña Bárbara by Rómulo Gallegos

Considered the quintessential Venezuelan novel and commonly summarized as the struggle between civilization and barbarism, Doña Bárbara narrates the dispute between the feisty protagonist and a landowner who after a time in the city returns to the countryside. Published in 1929 by Gallegos, who years later would become the first president of the Venezuelan democracy, the novel is an ode to the Venezuelan llanos, the region where Hugo Chavez was born. Besides bringing the exuberance of the plains in which fierce llaneros only fear the implacable ‘Doña Barbara’ and the spirits, the novel shows the richness of a region that is rarely discussed in our literature and which Chavez claimed had culturally molded him.