Islands live comfortably in the literary imagination. Cut off from the mainland and often small or negligible in population, they place characters in inescapable situations, amplify drama, and often suspend the normal rules of mainland society. And islands, as Rachel Carson points out in The Sea Around Us, are geologically transient, altering shapes and even disappearing completely; islands as symbols set the stage for other kinds of instability and ephemerality.

Being from the U.K., I’m also fascinated with the idea of islandness, and what it might mean to be an islander. When an island is not named in a novel, and therefore not tied to a specific geography, what does the notion of an island lend to the narrative, to the people that live there? What does the imagined island invoke?

My novel, Whale Fall, is itself set on an unnamed and fictional island, based on an amalgamation of islands orbiting the British Isles such as Bardsey Island (Wales), St. Kilda (Scotland), and the Blasket islands (Ireland) which, like the island in the novel, were facing challenges around depopulation, increasingly hostile weather conditions, and modernisation on the mainland in the first half of the twentieth century. The novel’s protagonist Manod, an eighteen-year-old girl who grew up on the island, dreams of a different life on the mainland and struggles to connect with the people around her; her physical isolation on an island manifesting in her interior life. On a small island surrounded by shoreline, Manod lives in-between land and sea, but also in-between her past and her present, her present and her possible futures, and between her community, her family and her ambitions.

The eight novels on this list are set on unnamed or fictional islands; making them not grounded in a specific geography of place, but in the idea of an island. These unnamed islands have a global reach across Europe, Asia, East Africa, and North America, but the islands’ conditions—of isolation, of insularity, of instability—point to similar underlying ideas of disruption, allegory, colonial legacy and environmental care, forming an archipelago of novels mapping their connections to each other.

How I Won a Nobel Prize by Julius Taranto

Taranto’s fictional island off the coast of Connecticut hosts the Rubin Institute, a millionaire-funded university staffed by the “cancellees and deplorables” of traditional academia.

It’s one of a few books on this list that uses an island setting for a fabular, allegorical narrative, the island setting allowing for a contained mini-society that reads heavy with symbolism. The novel is sharp and funny, skewering the notion of modern cancel culture with exile to a phallic building. Its explorations of academic and free speech are suitably messy and ungratifying; as on the mutable ground of the shore, you never know quite where you stand.

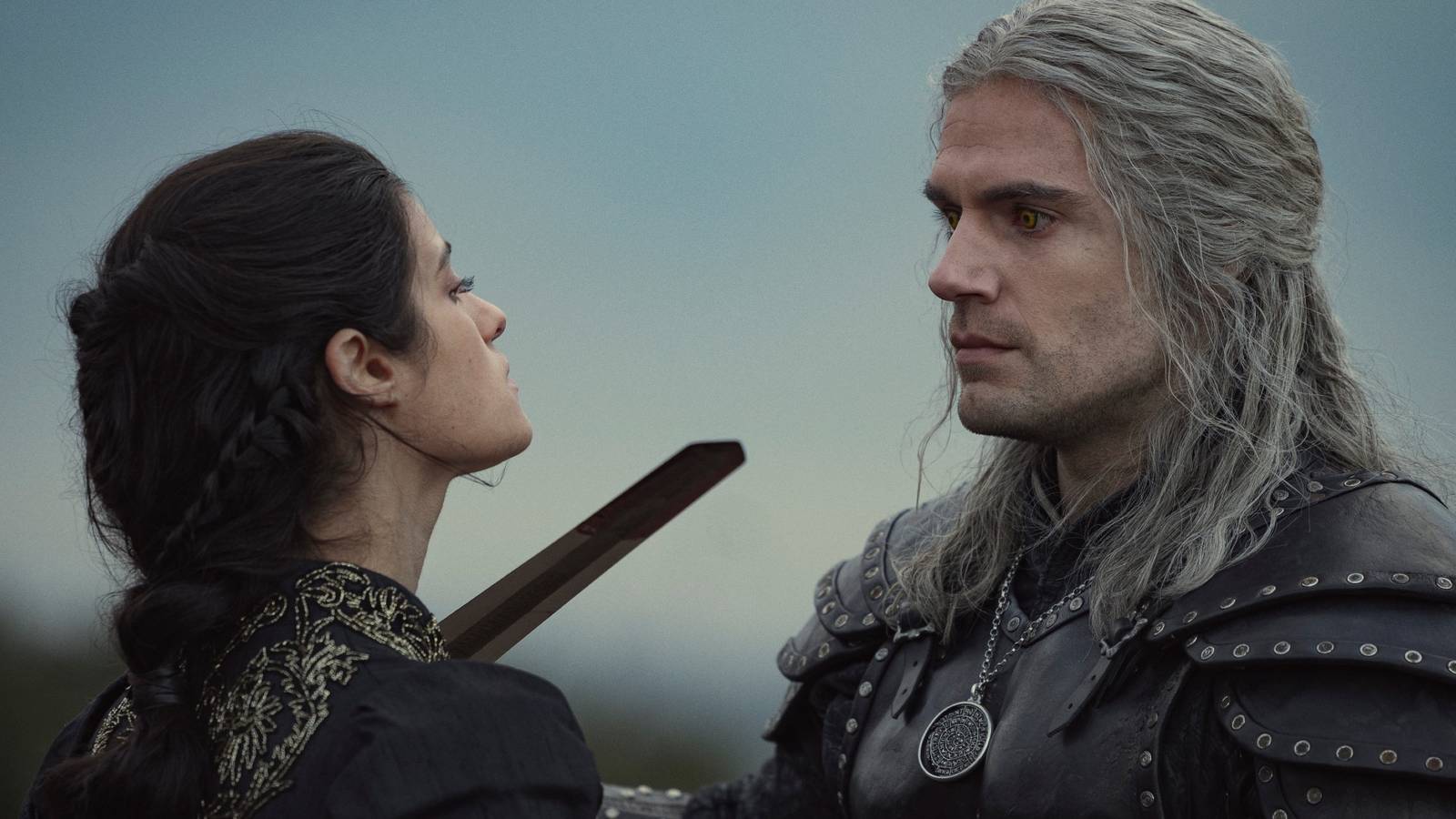

The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh

On a small, unnamed island, a single house holds a strange and otherworldly family. The three sisters at the heart of The Water Cure have been deliberately isolated from the mainland; their parents, Mother and King, tell them that it holds a toxic male population, and build their own society with elaborate, often cruel, rituals, and intense bonds to one another.

But when their perfect island seclusion is disrupted by three men washed up on a beach, the girls’ world begins to disintegrate. Mackintosh takes clear inspiration from other literary islands, The Tempest being an obvious homage, to set up this story of worlds colliding, and the island’s natural scenery provides a dramatic and ominous backdrop with gathering flocks of birds, grotesque washed-up carcasses of sea creatures, stormclouds moving in. I also love its island-y form: short, fragmentary pieces of story, narrated by different sisters, their interiorities constantly orbiting one another.

The Memory Police by Yoko Ogawa

The transience and instability of islands underpins Ogawa’s dystopian masterpiece, where objects and words disappear physically, and from memory, on an unnamed island off an unnamed coast. As the unnamed narrator finds ways to hide their editor, R, hunted by the authoritarian Memory Police, the island setting forms a topography of loss: animals migrate and never return, domestic and natural objects vanish, inhabitants reach for and fail to reach a forgotten language. It also stages the lives of displaced people – former hat-makers, ferrymen, boat mechanics, writers left adrift after the objects of their craft too disappear.

As a dystopia, the novel doesn’t lend itself to easy political analysis (and is all the better for it); Ogawa’s elusive, dream-like prose and meandering structure are punctuated solely and suddenly by ordinary people taking risks. The instability of the island, the sudden ease with which its shores can alter and dissolve, illuminates this allegory of loss and memory with fitting unease.

Tar Baby by Toni Morrison

Set on the Caribbean island estate of a millionaire white family, Tar Baby follows the romance of two Black Americans from very different worlds: Jadine, an art historian and fashion model who has been sponsored into wealth and privilege, and Son, an impoverished criminal-on-the-run.

When Son is washed-up on the edge of the Streets’ estate, he ruptures the class, education and racial divides that keep him in place, entering a new world of wealth, privilege, and freedom. The island setting stands for an erosion of boundaries, both physically between land and water, and socially. Subversion and rupture is a major concern across Morrison’s work, and the island asks for and offers new ways of living on shifting, tidal ground.

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson

A young girl and her grandmother spend a summer playing, talking and arguing on a tiny, unnamed Finnish island in this novel by the creator of the Moomins. Jansson’s eye looks to the minutiae of the island’s landscape to illuminate the intergenerational lens of the novel, concerning her narrator with the care and preservation of island moss, flowers, rocks. As later on Moonmin island, everything is transient, the island landscape prone to fogs, rainstorms, and tides that sweep things away and disrupt the plans of the creatures inhabiting it.

By the Sea by Abdulrazak Gurnah

By The Sea follows two narrators, both immigrating to the United Kingdom and both in flux; Saleh Omar, a political exile attempting to enter the United Kingdom from an unnamed East African island on a fake passport with the fake name Rajab Shaaban Mahmud, pretending not to speak English, and Latif Mahmud, arriving on a student visa and the son of the real Rajab Shaaban Mahmud, grappling with the recent revelation of their father’s secrets and second life. Gurnah examines the bureaucratic and emotional difficulties of movement and migration with an exacting and neutral eye. The novel’s movement between dichotomies, one named island and one unnamed, one ‘legal’ immigrant and one illegal, examines the inner landscape of alienation and exile, and the hollowness of national borders.

The Island of Doctor Moreau by H.G. Wells

A shipwrecked man is rescued by a passing boat and deposited on the eponymous island of Wells’s Sci-Fi classic. As in Taranto’s novel, Moreau’s island is the home of an exiled scientist, beleaguered for his vivisectional experiments on humans and animals. And as in many novels on this list, an island’s boundary-blurring of water and land creates a space where other boundary-blurring can take place. Moreau’s island is inhabited by the results of his experiments, a series of animal-human hybrids including Hyena-Swine, Leopard-Man, Fox-Bear Woman, Sloth-Creature, and Half-finished Puma Woman, who live according to their own set of surreal laws. Wells’s book has clear interest in the separation, connection, and interference of humans and nature, exploring instinct, morality, and Darwinian evolution in the surreal allegory offered by an island’s secluded world.

The Colony by Audrey Magee

I found The Colony greatly inspiring while finishing the edits for Whale Fall. Magee’s unnamed island has some geographical models in the peninsulas around the coastline of West Ireland, such as the Aran islands and Blasket islands, and clear literary heritage in J.M. Synge, W.B. Yeats, and Colm Tóibín. Yet as its title suggests, Magee’s island is deliberately unnamed to place its themes ahead of geography; it is a novel about colonialism, culture, and language.

Its drama, as with other titles on this list, concerns the arrival of outsiders: Lloyd is a London artist looking to revitalise his flagging career, and Jean-Pierre, a French linguist, charting and recording the island’s native Irish language. They clash over their mythologising of the islanders, whose numbers dwindle in the double-figures, and overlook their impact on this struggling community. While the story roots itself in an Irish perspective, with radio bulletins about the Troubles in Northern Ireland interspersing the narrative, it dramatises the legacy between colonised and coloniser with a global outlook.