I was born a year after the collapse of the Soviet Union in Moscow. My mother and I emigrated to the states in 1996. We were undocumented for 11 years, desperate for our green cards. I often wondered if Mom made the right decision in leaving. America was hard on us. We were alone. We had a whole family in Russia; a community that didn’t exist here.

Every time I asked my mother why we left she would close up. Most times she commented on how I should appreciate America instead of asking stupid questions. I was a freshman in high school when a kid in my English class asked me if Russia was “really that bad,” after our unit on Orwell’s Animal Farm. I didn’t know, so I started reading. I learned about the scarcity everyone living under the Soviet Union seemingly experienced. The paranoia. The isolation. The unknown. I filled in the gaps my mother refused to elaborate on with novels and memoirs. Even still, I couldn’t decide if becoming undocumented immigrants in the U.S. rather than citizens of Russia was worth it.

On February 24, 2022, as headlines of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shocked the world—I recognized, without a doubt, my mother made the right choice for us.

From the revolution in 1917 to 2022, this reading list contains stories of the decision and journey to leave Russia and the sacrifices that were made along the way.

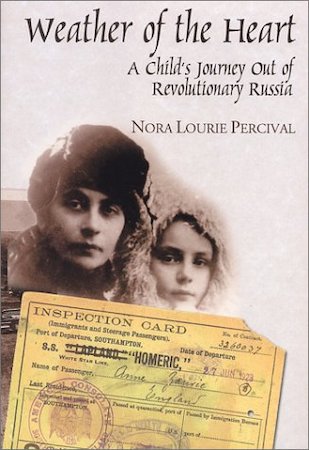

Weather of the Heart by Nora Lourie Percival

In March 2022 there was an exodus of 300,000 young adults from Russia. In September 2022, that number climbed to 800,000. Commentary on the “brain drain” effect as skilled and educated Russians flee abroad have been splashed across news articles since the beginning of the war. This “brain drain” has been happening since 1915. People have been slowly trickling out of Russia for the last century.

Nora Lourie Percival left Russia in 1922 with her mother. Nora’s memoir starts with her experience in her return k to the place of her birth, Samara, a city on the Volga River, after almost 80 years away. The memories then jump back to the early days of the Russian Revolution. She writes of her arduous journey out of Russia and why she had to leave as a child. The similarities of Russia in 1915 and Russia in 2022 are shocking.

Passages such as: “I am really thinking mostly of our poor Russia. She is losing so many of her best people in these wanton days. If I can save one or two for her, I must do it,” said by Pytor Ivanovich, Nora’s father’s friend, who is trying to convince her father to leave the country, are astonishingly similar to the headlines I read about Russia every day. The first half of the book describes life in Russia before and after the civil war. The memoir follows the trials faced by the author as she survives the civil war and then immigrates to America, taking care to describe both her own experiences and the collective experience of others like her.

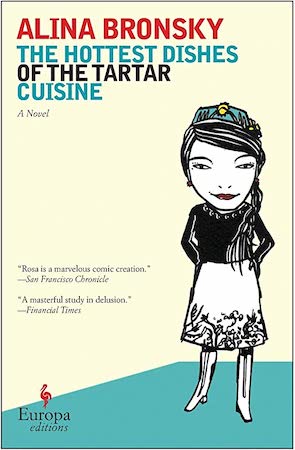

The Hottest Dishes of the Tartar Cuisine by Alina Bronsky

The Hottest Dishes of the Tartar Cuisine highlights the desperation that so often accompanies stories of immigration. Told from the perspective of Rosalinda, a critical and narcissistic Tartar woman, the story follows her tumultuous relationships with her daughter, husband, and granddaughter from the late 1970s through the 1990s. While moments of humor—from the sheer absurdity of the protagonist’s lofty opinion of herself and thinly veiled loathing of her family—punctuate most scenes, the core centers around the trauma endured by Aminat, her granddaughter, as her family’s dysfunction spins out of control. As food dwindles and hardships pile on, Rosalinda decides she must do whatever she can to get Aminat out of Russia, no matter the cost.

“’Sulfia,’ I said tenderly, ‘It’s for Aminat’ sake, don’t you see?’ She has no future in this country. It will eat her up and won’t even spit out the bones. You need to find a foreigner, Sulfia.’”

A Mountain of Crumbs by Elena Gorokhova

Elena’s Gorokhova’s memoir paints a picture of what growing up in the Soviet Union was like in the 1950s through the 1960s. Her lyrical language is loving and tender when recounting her memories of St. Petersburg, almost as though Russia was a family member. Her book describes her childhood, both lovely and awful. She ruminates on the beauty of her city and her appreciation for the arts and culture of Russia while also acknowleding the problematic parts of her heritage with a child-like lens, curious, but ultimately knowing something is intrinsically unfair about the life she was born into. For example: she asked her English language teacher what the word “private” meant. There is no word for private in the Russian language because the people of the U.S.S.R. had no privacy.

As a young adult, Elena starts considering what her life would look like outside of the iron curtain. In the last part of the book, Elena compares Russia to her mother and ultimately uses this reasoning to leave the U.S.S.R.: “

I want to leave this country, which, it dawns on me, is so much like my mother…They are both in love with order, both overbearing and protective. They’re prosaic; neither my mother nor my motherland knows anything about the important things in life: the magic of theater, the power of the English language, love….You can’t breathe, you can’t move, and you can’t squeeze your way to the door to get out.”

When the River Ice Flows, I Will Come Home by Elisa Brodinsky Miller

In her memoir, Elisa Brodinsky Miller asks what happens to Russia now? Set between the years 1914-1922, she finds cache of letters from her grandfather Eli written to his wife and children during the Russian revolution. For eight years, the family was broken up and without the resources to reunite with Eli in the United States. The correspondence between her family members helps her piece together what happened with her father’s family during the years they could not be together.

“The situation in Russia right now is such that in general one cannot say anything with certainty… Now Russia is undergoing changing times: what will result? There is no way to know. So in view of that to say anything in the present time about leaving or staying in Russia is very difficult,” written by Eli to Isor (his son) in December 1917. This book unintentionally parallels, through firsthand documents, the same questions Russians ask their country today. Elisa Brodinsky explains the history of Russia and gives context into what was happening historically at the time the letters were written, as well as how her own life mirrors her grandfather’s life in her search for opportunity.

Only One Year by Svetlana Alliluyev

Only One Year, written by Josef Stalin’s daughter, is a memoir which elucidates her decision to leave in 1967. The book starts with her going to India to mourn her Indian partner and spread his ashes in the Ganges. After some time in India, Alliluyev realizes she doesn’t want to go back to her home in the U.S.S.R. and she makes the painful decision to abandon her family and culture and defect to the United States.

“I began to feel any physical pain or injury inflected on others as if it were my own pain. Tears shed by others brought tears to my eyes. I learned to weep and laugh with my whole being. My heart was thrown open now, which previously had been compressed and jammed.”

Like a Drop of Ink in a Downpour: Memories of Soviet Russia by Yelena Lembersky

This memoir is excellent if you want to understand how difficult leaving Russia was right before Glasnost and Perestroika. Told from two perspectives: the mother, Galina, and the daughter, Yelina, the memoir describes the trials and tribulations faced by Galina of getting her family out of the country and the painful sacrifice of doing so. The story starts with Yelina’s mother being sent to a gulag, leaving Yelina with a stranger who later tells her she can no longer care for her. Yelina is alone in Russia and on the cusp of puberty, relying on different people to offer her food and shelter until her mother comes home.

Part two switches to Galina’s perspective as she explains her sentencing and life in a gulag in the first place. The third part of the book, told again from Yelina’s perspective, answers the question of whether the mother and daughter were finally able to leave their motherland.

The Orchard by Kristina Gorcheva-Newberry

Best friends Anya and Milka seem to have a typical Russian childhood. As they change and grow together, their motherland also goes through changes, as though Russia was also trying to grow up. At the precipice of the novel, an incident alters the trajectory of the friends’ fate, ultimately leading Anya to emigrate to America, not returning to her country for 20 years.

“I believed in the future of my country and that I was contributing to it by doing my job and raising my family… When the nineties hit, we all understood that it wasn’t enough, that the boat wars rotten through. We were all sinking, no matter how fast or hard we paddled.”

A Terrible Country: A Novel by Keith Gessen

A Terrible Country tells the story of a postgrad Russian American returning to Russia to take care of his ailing grandmother. He struggles to understand the post-Soviet Russian landscape where cute cafes with high priced cappuccinos sit across the street from the KGB building where thousands were killed in the Soviet era. Andrei spends his days in the apartment playing anagrams with his senile grandmother and roaming Moscow to try and find Wi-Fi to work remotely at the university. At night, he looks for hockey games to blow off steam. When the economic crisis of 2007 hits, his brother pushes him to sell the apartment, promising to find another place for their babushka to live. After finding himself in a group that call themselves the “Octoberists,” he finally feels like he’s acclimating and decides to move back to Russia permanently. When the Octoberists are targeted by the police for their political mishaps, Andrei has to decide whether his new life in Russia is worth it, or if he should leave, once again, to America.