I was fifteen when my mom announced that we’d be moving to the US because she had a new job there. My younger brother was not thrilled by the prospect of the move and tried to negotiate a way to stay in Nigeria, perhaps with relatives or friends. I, for my part, was ecstatic, my head filled with scenes from the American shows I’d seen on TV, like A Different World and The Cosby Show. I remember asking my mother what winter was like, since she’d lived in New York while she was in graduate school. The freezer, she said. On a humid, 85-degree day in Ibadan, I stuck my head into the freezer compartment of our standing fridge and smiled as the icy blast soothed my overheated face.

Months later, when our flight landed at Boston’s Logan Airport and a chill that I had never imagined could exist drilled into my bones, it was my turn to ask whether I could go stay with one of my uncles in Ibadan until my mom came to her senses. How on earth could anyone live in this kind of cold? It wasn’t just the icy weather I found myself navigating, it was the people who couldn’t understand my accent, the strange food, the high school gym teacher and track coach who took one look at me and said excitedly, you’re built like a gazelle. I did my best, but the gym teacher gave me a D, because no matter how hard I tried, I galumphed like a giant tortoise.

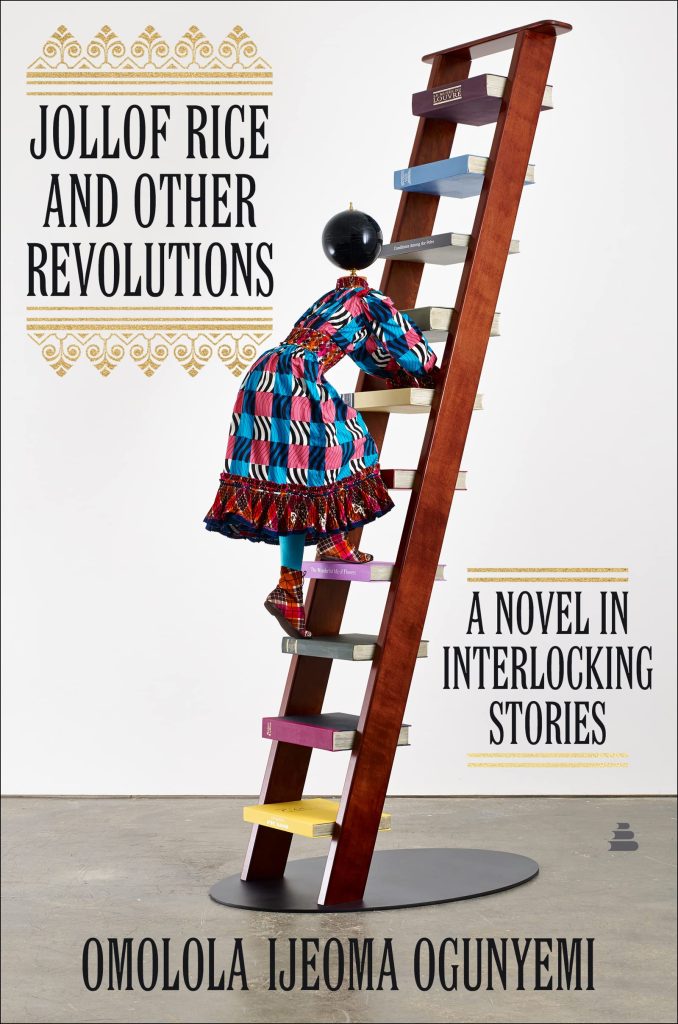

All of these experiences came rushing back when I started writing my linked story collection, Jollof Rice and Other Revolutions—the longing for the sights, sounds, tastes, and smells of home. The disappointment when, at last, I visited, and things weren’t quite as I remembered. The feeling of never quite fitting in, in either place. The four friends at the core of my book meet in an all-girls boarding school in Nigeria, much like the one I attended. Their lives take them to the US, where they finish college, work, marry, divorce, remarry, relocate to Nigeria, and return to the US, all the while holding on to that special connection forged when they were nine and ten years old.

I find that I gravitate toward books about migration, feel my insides clench when the writing fully captures that sense of dislocation, the nostalgia, need to adapt, to belong. I’m drawn to stories that embody the hope that people will see you as you truly are, as you wish to be seen, and not invent some caricature of you. Below are seven collections that do just that.

A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times by Meron Hadero

Meron Hadero’s A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times is a brilliant and sometimes heartbreaking collection that goes back and forth between Ethiopia and different parts of the US. In fifteen stories, she examines the lives of refugees and immigrants: what it’s like to move from one country to another until you finally land in the US, to adjust as a child who must quickly learn about race/caste in America. The collection also examines how the next generation negotiates the duality of their Americanness and ancestral ties to the country that birthed their parents. In “The Wall,” a pre-teen Ethiopian refugee who relocates to the Midwest from Germany makes a connection with a retired professor who fled Berlin following Kristallnacht through their shared fluency in German. “Sinkholes” recounts a disastrous lesson in a 1970s Florida classroom in which a teacher rounds off teaching Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man by asking a classroom with only one Black (immigrant) child what her students understand about race by writing slurs on the chalkboard. The final story, “Swearing In, January 20, 2009,” describes the narrator’s feelings of hope and possibility following the 2008 US presidential election, and then the despair stemming from the backlash that continues to the present day. Hadero also won the 2021 Caine Prize for African Writing for “The Street Sweep,” a story in this collection.

Better Never Than Late by Chika Unigwe

Unigwe’s collection is a compact, gut-wrenching set of linked stories that follows the lives of a small group of Nigerian immigrants in Turnhout, Belgium. We meet Prosperous, uncomfortable hostess of weekend Nigerian gatherings, who finally asks her husband, Agu, “How can you just sit there and watch your friend use a woman like that?” after more than one of his associates marries an unsuspecting European woman for papers. In “Cunny Man Die, Cunny Man Bury Am,” we see the tables turned. In other stories, we feel the grief of a young mother who suffers an unspeakable loss and the disbelief, terror, and unexpected shame that follow a woman’s violation on her train ride home. All of the stories capture the frustration and sense of defeat that sets in when immigrants who had college degrees and decent paying jobs (that afforded them cars, big houses, and maids in Nigeria) end up working dead-end menial jobs in Belgium because of the language barrier, their pride preventing them from returning home to Nigeria and admitting that leaving may have been a mistake.

Afterparties by Anthony Veasna So

The late Anthony Veasna So’s loosely connected stories feature Cambodian immigrants from Northern California’s San Joaquin Valley. The characters are complex, haunted by loss, reincarnation, genocide, and unacknowledged PTSD. The next generation grapples with different identities: Khmer, American, queer. In “The Monks,” Rithy spends a week at a temple to honor his dead (and deadbeat) father, all the while missing his girlfriend Maly and enduring the contempt of a monk who can’t understand why anyone whose family was devastated by genocide would sign up to join the US Army. In “Human Development,” the narrator, in his twenties, hooks up with Ben, a forty-something, previously closeted Cambodian man. He worries that much of Ben’s attraction comes from a sense of obligation or duty, saying “I can’t be with a Cambodian guy just to be with a Cambodian guy.” In “Generational Differences,” based on true events, a boy discovers that his mom survived a white supremacist school shooter who took the lives of five children and injured thirty more, “to defend his home, … against the threat of us, a horde of refugees, who had come here because we had no other dreams left.”

What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky by Lesley Nneka Arimah

Arimah won the 2019 Caine Prize for African Writing. What It Means When a Man Falls from the Sky explores the contours and limits of power for young women of Nigerian descent. In “The Future Looks Good,” one sister is mistaken for another by a young man, a domestic abuser “… unused to hearing no ….” “Wild” is the story of a Nigerian American girl two months away from college, sent to Lagos to live with her aunt and cousin as punishment for “acting wild”—kissing boys; taking ecstasy; and getting high with her best friend, the only other person of color in her grade, among other offenses. In the final story, “Redemption,” the thirteen-year-old narrator is obsessed with thirteen-year-old Mayowa, her neighbor’s fiery new house help, who “the day after [they] met, … sent a missile of shit wrapped in newspaper like a gift.” Two of Arimah’s stories from this collection, “What it Means When a Man Falls from the Sky” and “Who Will Greet You at Home,” were shortlisted for the 2016 and 2017 Caine Prize for African Writing.

Ayiti by Roxane Gay

The fifteen short stories in Roxane Gay’s Ayiti swing between Haiti and the US, giving an unflinching portrait of Haitian immigrant life and the sometimes laugh-out-loud funny ways in which immigrants cope with othering. Several of the stories are flash fiction, a page or less. There’s Gerard, the defiant young man in “Motherfuckers,” who tells his non-French-speaking teacher “Je te deteste,” (I hate you) when she chirpily notes his accent and asks him to say something in French. In “Voodoo Child,” the Catholic narrator takes full advantage of the ignorance of a college roommate who, upon hearing that she’s from Haiti, assumes that she practices voodoo. “There is No ‘E’ in Zombi, Which Means There Can Be No You or We,” gives the story, set in Haiti, of Micheline, who wishes to hold on to Lionel, a man resistant to commitment. “Sweet on the Tongue” is a harrowing story that follows a young Haitian American woman whose honeymoon in Haiti with her new American husband ends in a kidnapping.

Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri

Winner of the 2000 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies is a powerful, yet subtle collection of nine stories that examines the lives of Indian Americans and Indians, as well as relationships with people from Pakistan following partition. “A Temporary Matter” chronicles the lives of a couple as they spiral apart in the aftermath of a stillbirth. In “Interpreter of Maladies,” an Indian American woman on vacation in India with her husband and three children unburdens herself to the chauffeur and part-time translator shuttling her family around. Bibi, a young woman prone to seizures, is the focus of the story “The Treatment of Bibi Haldar,” set in India. After her mother dies in childbirth, Bibi is raised by her father, and then taken in but mistreated by her cousin Haldar and his wife after her father’s death.

The Dew Breaker by Edwidge Danticat

The Dew Breaker, from Edwidge Danticat, features nine stories that revolve around a member of the Tonton Macoute (torturer for Haiti’s Duvalier regimes) and the people whose lives have been impacted by his misdeeds. We come to understand the Dew Breaker’s life in New York as a US immigrant, as well as his past in Haiti through the effect he has on different members of the Haitian American community. We meet his daughter, learn the terrible secret that complicates his relationship with his wife, and learn about the lives of his victims and their descendants, some of whom recognize him, or think they recognize him, in New York.

.jpg)