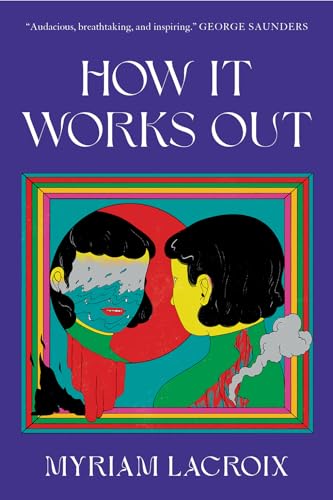

When I started writing my first book around ten years ago, I had very few role models for the type of queer, genre-bending writing I wanted to be doing. While I now know those books existed, at the time they weren’t talked about in my literary circles, where the minimalist realism of writers like Raymond Carver was seen as the highest possible literary achievement. As a result, I wrote How It Works Out with what feels like very few roadmaps, which, as a queer person, isn’t new to me. In some ways, How It Works Out’s unique concept—a queer relationship multiverse of the Everything Everywhere All at Once variety, in which a queer couple is reinvented across timelines and in wildly different realities—came out of that very lack of roadmap. As a young person with no queer elders in her life, I entered my first relationship with a woman without any idea what to expect. How It Works Out imagines strange and surreal outcomes to a queer relationship because I had no idea how to be in love, or what happened once you were. The main character bears my name and is reinvented, over and over, because I was trying to make sense of how I fit into the world.

One of the best parts of being queer is getting to throw out old narratives to come up with ones that feel better suited to us. And though navigating the world with a vague sense of our history and little intergenerational guidance can be bewildering, it also opens us up to invention—makes it necessary, even. In the years since I started writing How It Works Out, the literary landscape has changed drastically, and queer writers are finally getting credit for the bold and innovative ways in which we are shaping—and have always shaped—literature at large. Though there is still much room for improvement—with people of color, women, and especially trans people frequently excluded from mainstream queer representation—the number of queer writers skillfully breaking every rule of genre and form, and being given a platform to do so, feels unprecedented in my lifetime. The following seven books are a thrilling gateway into the world of queer genre-bending and formally innovative literature.

Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) by Hazel Jane Plante

I love experimental books most when their reinvention of genre and form arises naturally from emotional truth. Hazel Jane Plante’s stunningly written novel Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) takes the shape of an encyclopedia about a fictional television show called Little Blue. By alternating between the rollercoaster narrative of Little Blue and memories of Vivian, with whom the main character watched the show before she died, Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) tells the story of an unforgettable friendship between two trans women, the main character’s unrequited romantic love for Vivian, and a grief as devastating and beautiful as Vivian herself.

Blackouts by Justin Torres

In Blackouts, Justin Torres turns a true artifact—a medical textbook called Sex Variants: A Study of Homosexual Patterns—into a series of erasure poems through which readers can hear the voices, largely redacted from history itself, of the queer subjects of dehumanizing studies conducted in the early 20th century. Torres uses Sex Variants to tell the story of Juan, an elderly gay man dying in the desert, and the younger friend he calls nene, whom Juan met when nene was barely eighteen and the two were institutionalized for their homosexuality. As Juan slowly dies with nobody but nene at his side, the two revisit their lives, interweaving their stories with those of Sex Variants’ subjects and creators.

In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

One of the most genre-defying memoirs in recent history, Machado’s In the Dream House uses the trope of the haunted house to make sense of the psychological and physical abuse she endured in her first relationship with a woman. Playing with the genres of folk tales, cultural criticism, historical nonfiction, choose-your-own-adventure books, among others, In the Dream House is an important deviation from the coming-out-as-salvation narrative, a humanizing reminder that queer relationships are just complex as straight ones, and are no less susceptible to domestic abuse. Revolutionary in form and content, In the Dream House is a must-read.

Open Throat by Henry Hoke

Written from the perspective of a queer, gender-fluid mountain lion, Open Throat reads like a prose poem bursting with the sort of narrative tension that can make readers rip through 160 pages in a single sitting. Slowly starving in the drought-devasted land under the Hollywood sign, Hoke’s mountain lion listens in on passersby, a collage of decontextualized dialogue that paints a telling portrait of “ellay”’s human inhabitants. When a climate catastrophe forces them into the city, Open Throat’s narrator experiences for themself the tenderness and brutalities inherent to the human world.

LOTE by Shola von Reinhold

While volunteering in an archive, history-obsessed Mathilda discovers the photograph of the forgotten Black modernist poet Hermia Druitt, a lesser-known member of the queer and extravagant Bright Young Things. Her ensuing research spiral leads her to an eccentric arts residency in the European town of Dun, where Druitt once lived, and sets her on the trail of a secret society of West African, proto-communist, lotus-eating luxury worshippers. Blending documented and imagined histories, and writing their own historical book-within-a-book, von Reinhold writes a compelling historical mystery, a poignant investigation of race and gender identity, and a stunning work of aesthetic theory.

The Show that Smells by Derek McCormack

Anyone who reads Derek McCormack’s The Show that Smells won’t be surprised that it has gained a passionate cult following since it was published in 2008. Narrated by Derek McCormack, a reporter for Vampire Vogue, and set largely inside a mirror maze, The Show that Smells features Elsa Schiaparelli (a vampire designer vying for the soul of country legend Jimmie Rodgers), Coco Chanel (Schiaparelli’s rival, whose poisonous Chanel N°5 is her deadliest weapon), the Carter family (down-home singers by day, vampire killers by night), and a whole cast of country stars, monsters, and queers. An unhinged phantasmagoria of camp, The Show that Smells creates a form of its own, littering its own pages with typographical sequins, mystical mantras that cause characters to appear, and blood.

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

A beloved staple, Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts tells the story of her relationship with Harry Dodge, a gender-fluid artist undergoing hormone therapy, as well as her own pregnancy and desire to build a family with Dodge. Blending memoir with theory, The Argonauts uses the works of Butler, Sedgwick, Barthes, Winnicott, among many others, to make sense of everything from gender, family structures, motherhood, identity politics, and anal eroticism. In addition to the central metaphor of The Argonauts—“Barthes describes how the subject who utters the phrase ‘I love you’ is like ‘the Argonaut renewing his ship during its voyage without changing its name.’”—the poetic precision with which Nelson writes this intellectually rigorous investigation of love puts The Argonauts in a league of its own.