Queer characters deserve happy endings. And after everything we’ve been through—hiding our identities, hating ourselves, loving in secret, and living through stigma and fear—queer people deserve everything. We deserve the meet-cute, the toe-curling sex, and the over-the-top destination wedding. If I had my way, we would all have our student loans forgiven and become instant lottery winners when we turned thirty.

Yet, we all know that life doesn’t work that way. Happy queer couples fall out of love and break up or divorce. Queer people are human, and all humans eventually die. Not to be a complete buzzkill, but I prefer such messy realism over fantasy. For one, I learn from messy queer characters and stories. I learn from these characters’ contradictions, blind spots, and how they navigate their shadow selves as they grow and develop. Only through personal transformation can queer people survive and eventually thrive toward liberation, and this path is often long and circuitous. While pat endings serve a dual purpose, providing both hope and escapism, they frequently do not do justice to queer stories, which are often complicated by childhood trauma, stigma, marginalization, and other complexities.

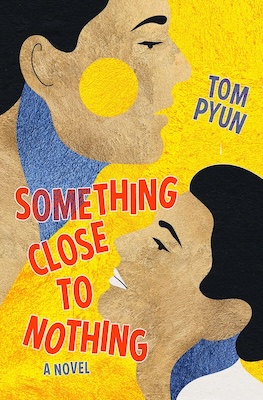

In my debut novel, Something Close to Nothing, the dual protagonists, a mid-thirties professional gay couple in San Francisco, appear to have it all: a loving relationship, high-paying careers, a baby on the way via a surrogate, and a single-family house in San Francisco. Yet, Wynn and Jared’s shadow selves, their arrogance, anger, selfishness, and inability to communicate with each other lead to the downfall of their relationship. While they develop and grow throughout the story, I didn’t necessarily feel either was “ready” for a happy ending. They had too much growing up to do. I played with the book’s ending over the years and considered a few storybook and even “neutral” scenarios for them, but eventually landed on a messy one (no spoilers!). I knew the ‘truest’ ending would leave the reader with the precise lesson I sought to convey. Moreover, I considered the many queer stories that had come before me and found that almost all of them featured messy protagonists with equally or even messier endings. Here are my favorites:

Brokeback Mountain by E Annie Proux

I came for the gay cowboys and stayed for the crystalline prose in this classic novella. Two young, closeted Wyoming cowboys fall in love but can’t be together for obvious reasons. Proulx publicly stated that she wished she had never written the novel due to rabid fans chastising her for the tragic ending. But given the time and setting, could it have ended any other way? Harsh landscapes yield harsh outcomes. Proulx aptly demonstrates how homophobia and violence not only destroy love but also lives. What I found most heartbreaking was how Ennis’s fear of coming out may have saved his life but also made the reader question whether life was worth living without love.

A Little Life by Hanya Yanigahara

The novel opens like modern-day fan fiction with four young men, recent college graduates with promising futures, living in a run-down apartment in New York City’s Soho neighborhood. Yet, the story turns very dark, zeroing in on Wilhelm’s harrowing story of childhood sexual abuse. In an interview, Yanigahara said she hoped to write a “protagonist who never gets better.” In this gripping novel, many well-intentioned, kind, and loving characters attempt to save Wilhelm from his pain. The story made me consider the friends and acquaintances who have been lost to suicide and whether there are some people we can’t help due to living with unceasing and unknowable amounts of psychic and physical pain. These ruminations and the consecutive nights I stayed up reading resulted in me coming down with pneumonia soon after finishing the 832-page novel.

Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison

The recent death of Allison has put a spotlight on her rich literary legacy. The novel, based on Allison’s fraught childhood, sheds light on child abuse and rape yet is ultimately about multi-generational poverty, addiction, and abuse. At the end of the story, the protagonist, Bone Boatwright, is physically safe yet fully aware of how her childhood and her mother’s abandonment have scarred her, jeopardizing her tenuous future. “What would I be like at fifteen, twenty, thirty? Would I be as strong as she had been, as hungry for love, as desperate, determined, and ashamed?”

Memorial by Bryan Washington

In his lyrical novel, Washington’s dual protagonists, Benson and Mike, are a young gay male couple in Houston whose relationship is in a fragile state. When Mike’s father in Japan falls ill, he abruptly leaves their home in Houston to be by his side. Told in alternate voices, Washington aptly demonstrates how couples sometimes need to grow apart and evolve individually to come back together better and stronger, or not. Washington leaves the ending artfully ambiguous, yet we are left with the belief that whether Benson and Mike decide to reunite or go their separate ways, the kids will be all right.

Edinburgh by Alexander Chee

Chee’s gut-churning debut explores childhood sexual abuse. A charismatic choir director grooms and molests a shy Korean-American boy named Fee and his choirboy friends. The years after, are mired in guilt and shame for never reporting what he observed and experienced. The novel turns dark when Fee switches roles—from the perpetrated to a perpetrator—exploring his shadow side and showing the reader that we cannot escape our pasts unless we face them head-on.

All This Could Be Different by Sarah Thankham Matthews

In Matthews’ coming-of-age novel, Sneha, a recent college graduate, has moved to Milwaukee to begin her first grown-up job. In her own words, she is ready “to be a slut.” Complicating this sexual awakening is her keeping her sexuality a secret from her parents, who have recently returned to their native India. Instead of swapping and sharing sapphic beds, she falls hard for Marina. While the two do not end up together, Sarah’s friends are there to hold her, showing her love can come in many forms.

My Government Means to Kill Me by Rasheed Newson

In this ingeniously plotted fictional memoir, Trey is a queer Black teen from Indiana who has forsaken his trust fund to make his way in 1980s New York City. Newson takes us along Trey’s lively and naughty adventures, from bad jobs to frequent escapades to a Harlem gay bathhouse. Trey’s political awakening leads to activism at the start of the ACT UP movement. Newsom carefully threads a heartstopper of a finale, where Trey saves the life of one friend and ally at the expense of another, shedding new light on the adage of “the end justifying the means.”