The late Chuck Kinder once told me, “Fiction should be a fist.” Meaning fiction is a medium suited to emotional honesty, the place to have adult conversations. To engage with the world in all its complexities, and, often, its ugliness.

For me, this has meant writing characters who either confront oppression, assist in oppression, or make the choice to ignore and thus abet oppression. To separate their emotional lives from the political is to ignore the reality of human existence. Our world isn’t burning someone is setting the world on fire, and, whatever their flaws, the protagonists in my new collection, Weird Black Girls, are politically engaged people.

Poetry is where I’ve often turned to for confrontational writing from marginalized voices. Thanks to its brevity, poetry is, in many ways, the genre best suited for critiquing the status quo. However metaphorical the poet, they only have so much space to get their point across. The poets on this list use art as both archive and argument: an archive for those who cannot broadcast their viewpoint through textbooks and news outlets; an argument for those who cannot force their will with guns.

Don’t Call Us Dead by Danez Smith

Seven years after publication, Danez Smith’s breakout collection remains an essential ode to queer existence, as well as polemic against white supremacy. Largely writing in response to the racist lynchings that have become a defining part of 21st century America, the poet not only confronts police murder, but commits the ultimate rebellion of celebrating their own life. Filled with poems expressing fear regarding their HIV diagnosis, Smith remains proudly queer, neither forgetting nor forgiving the system that allowed the plague to flourish. What stands out to me after all this time is the humanity in this collection. “I tried to love you,” Smith tells white people in “dear white america,” even as the inclusion of “you’re dead, america” reminds the reader that hate rules in this country. And yet, for all Smith’s rage and weariness, there remains, at the core of the book, that most forbidden love in the American conscience—the deep, joyful, unflinching love for black people.

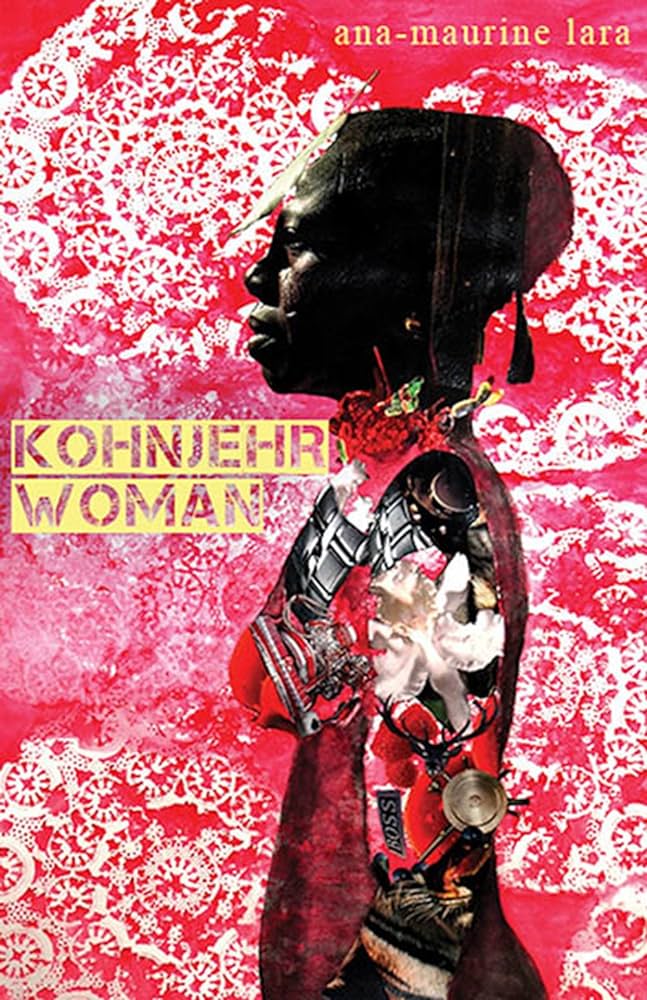

Kohnjehr Woman by Ana-Maurine Lara

In this narrative-driven collection, a woman from the Caribbean is sold to an antebellum plantation. For the crime of poisoning her master, her tongue has been cut out. That doesn’t stop the conjure woman from wreaking havoc on the tyrants who run the place, nor from expressing her thoughts in beautiful poetry written in patois. As the other slaves come to know the woman called Shee, her thoughts meld more and more with their perspectives, painting a picture of black folks joining in community. An underrated gem about the black holocaust.

While Standing in Line for Death by CAConrad

“We are time machines of water and flesh patterned for destruction, if we do not release the trauma.” Veteran poet CAConrad’s 2017 collection is a response to unspeakable pain: the murder of their boyfriend in a horrific hate crime. Grief and survival drive these poems, but never so much that Conrad forgets anger. In nonfiction sections interspersed throughout the book, Conrad documents their personal rebellions against animal imprisonment, the military-industrial complex, homophobia, and Christian extremism. Conrad is equally antagonistic towards form, shaping their poems like knives to cut anyone who’d dare harm an innocent person, or, from another lens, like bodies standing proudly upright. A ferocious work of queer rage.

Things You May Find Hidden in My Ear: Poems from Gaza by Mosab Abu Toha

“Through it all, the strawberries have never stopped growing.” A frank account of the violence visited upon Palestinian people, these poems are filled with shrapnel, F16 roar, twisted bodies, and funerals. Hand-in-hand with these visions of state terror are deftly crafted lines celebrating the land of Palestine down to the tiniest plants that dwell there. There’s even a strain of deadpan humor running through the book. A defiant statement from a talented poet.

Whereas by Layli Long Soldier

Much of this collection is in response to President Obama’s 2009 apology to Native Americans for the genocide and oppression they experienced: an apology that Obama, rather than publicly declare, had read in private to a handful of tribal leaders. An Oglala Sioux poet, Long Soldier uses language to interrogate the role that language plays in genocide. She bluntly translates government doublespeak. (“One should read, the Dakota people starved.”) She turns the word whereas with its implication of resolution into an anaphoric indictment. She carves up official documents into erasure poems and Mad Libs and fragments; angles those documents into hills the reader must climb to stand above bureaucratic white noise, or, in other cases, descend right back into the violence. Long Soldier’s writing, filled with disdain for those who whitewash genocide, is as captivating as it is relentless.

Birthright by George Abraham

In the forward by M.H. Halal, they pose the hard question about speaking to oppression: “How do I write this without mentioning the obvious oppressor? An oppressor who deserves no more space in our minds, in our imaginations.” To honor the experience of being Palestinian, George Abraham speaks and speaks. Of all books on this list, this one is the densest. Words cover the page like black rivers, poetry and prose, odes to everything Palestinians have lost written in a multitude of poetic forms. Abraham gives genocide no respite, speaking directly to murder and rape committed against his people. This is also a queer work. The homophobia Abraham experiences is countered with sensitivity towards the reasons toxic masculinity has spread among his family and peers. To discuss the lyricism in these ambidextrous poems would be nowhere near as effective as encouraging you to read them. This is poetry against annihilation.

If They Come For Us by Fatimah Asghar

The word intersectionality gets used in reference to the commonalities between different groups. Asghar writes of the intersectionality within her own identity. Much of the book addresses atrocities committed during the Partition of India. From there Asghar addresses the immigrant experience, post-9/11 islamophobia, and the anxieties of being a brown person during this surge in white nationalism. While her subject matter is heavy, her approach is playful. There is joy in the way she crafts poems as crossword puzzles, film treatments, bingo cards, and floor plans; breaking form to express the disjointedness in being othered. Speaking back to oppression is just one motif in this slim yet sprawling collection, loaded with imagery and deep empathy.