The most compelling horror novels are those that resent the very rules of their own genre. These books throw their elbows around and demand more space, pushing against the parameters, which quickly become elastic, until the novels defy easy categorization. To call them horror, then, is a disservice, but so would calling them “cross-genre.” They stand as good books that do whatever they please—and in the course of their doings, they make you feel very strange.

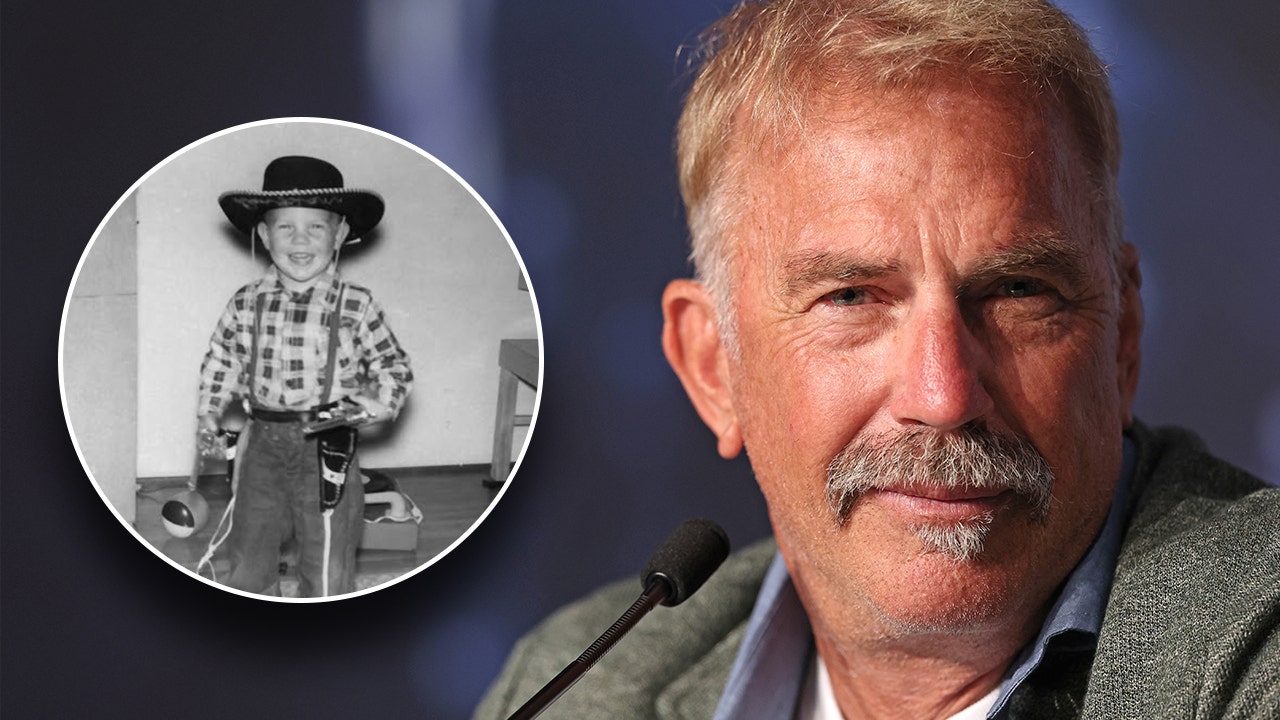

I’m an emotional writer. When I try to be calculating, I write stiff and spiritless fiction. Instead, I try to write toward a feeling. If that sounds like a messy enterprise it’s because it is—but feeling, more than intellect, is what I’m looking for in art. In the case of my novel A Brutal Design, I set out to write a book that might fill others with the same matrix of feelings that, to me, embody the best of horror literature. These are the ugly interstices between home and displacement, transparency and conspiracy, the real and the unreal, the question and the answer. To me, any book that splashes around in those mucky areas is worth reading, and may even make me feel something.

The books on this list are horror novels that might scoff at being called horror. In some cases, they brush against the genre incidentally; in others, they wage outright war on it and emerge barely scathed. But in all cases, they make me feel deeply strange in new ways, and that’s the whole point.

The Cremator by Ladislav Fuks, translated from the Czech by Eva M. Kandler

As a genre, horror is predicated on tropes, and the best of it finds ways of subverting those tropes in unexpected ways. For horror that targets the human psyche, this often means pushing people to and beyond their limits and reveling in the deranged aftermath. In The Cremator, Ladislav Fuks’ brilliantly sinister novel set during the 1930s, the soul in extremis belongs to Karel Kopfrkingl, a crematorium operator in Prague. Obsessed with class, freakishly fascinated by Tibetan Buddhism, and obsequious to an embarrassing degree, Kopfrnkingl is easy prey for the ubiquitous Nazi propaganda swirling around Europe. Whether a result of his gruesome chosen profession or the oppressive atmosphere of hatred building in the streets, Kopfrnkingl gradually transforms from a peculiar yet professional family man into an agent of death. When Reinke, a visiting former compatriot and proud Nazi, persuades him that the “drop of German blood” in Kopfrnkingl’s racial makeup makes him special, it’s all the cremator needs to find his purpose as a heroic liberator of souls from their bodies—including those of his family.

The Passion According to G.H. by Clarice Lispector, translated from the Portuguese by Idra Novey

If Gregor Samsa is who you think of first when you think of fictional cockroaches, then the cockroach at the heart of this existential nightmare should be the second. The titular G.H. is a bourgeois Brazilian sculptor who cannot recall the name or face of the maid whose quarters she enters to clean—but no matter: her thoughts dissolve when, upon opening the wardrobe, she encounters a cockroach. In fright, G.H. crushes the wretched thing halfway through the door in such a way that its carapace is stuck, oozes viscera, slowly dying. Yet, instead of moving on with her chore, the site of the dying insect grabs G.H. by the soul in a vice grip, preventing her from leaving the room and forcing her to confront the horrors — and joyous revelations — buried deep within her. The breathless plunge into the self that follows, represented by Lispector’s both philosophically lucid and addled prose, culminates with one of the most nauseating, yet enlightening, actions in fiction.

The Black Spider by Jeremias Gotthelf, translated from the German by Susan Bernofsky

Don’t be afraid of its publication date. This bitter novella about the dangers of indulging in sinful excess is horrifying, uncanny, and just waiting for Robert Eggers to adapt it for the silver screen. Though very much a Christian morality tale, complete with lessons-to-be-learned, The Black Spider pulls no punches in depicting the dark side of a souring agreement. Jeremias Gotthelf, the Swiss pastor who penned this tale, imagines in gleeful detail the punishment exacted on a mountain village of peasants who make a deal with the Devil in exchange for his help in assuaging the merciless lord of their hamlet. All the Devil asks in return is the life of an unbaptized newborn. Unwilling to hold up their end of the bargain, the villagers incur the Devil’s hellish revenge in the form of a murderous black spider — a stand-in for the plague — that grows out of a dark spot embedded in the putrid flesh of a woman’s cheek and preys sadistically on the villagers.

The Notebook by Ágota Kristóf, translated from the French by Alan Sheridan

The first book in a trilogy, The Notebook is the story of a pair of nameless twins who live with their grandmother in a European village during World War II. The hypothesis of this relentlessly bleak, ferociously disturbing experiment of a novel suggests that a person must descend deep into nihilism to survive war. In short, one must do whatever it takes. You won’t find The Notebook in a bookstore’s horror section; it does not conform to any of horror’s typical tropes. Instead, its horror lies in the depths of its perversity and depravity, a kind of Eastern European Cormac McCarthy novel, but without the bravado or decoration. This is a crude, mean novel about a crude mean thing. The twins treat their odds of survival with a disquieting rationalism, recording the results of their successful strategies in the notebook you are reading, and Kristóf’s writing is as harsh and blunt as their behavior. By far the most harrowing novel on this list, The Notebook’s true horror lies in its proximity to real life.

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell

Argentinian writer Samanta Schweblin’s short first novel achieves its triumphant sense of unease through the economical use of information. The book is comprised largely of unmoored dialogue, and the story that unfolds does so with great ambiguity. We are lost, but buoyed along by the sense of a near mystical presence lurking in the shadows. That presence may very well be, in fact, the existence of worms. We come to learn that Amanda is dying in a rural clinic, and that David, a child, is interrogating her. We learn that David became sick from drinking water from the river. We learn that David isn’t the only sick kid; other children in their small and neglected town were born deformed, missing vital parts or boasting an excess of them. And finally, we learn the truth, and it’s hardly supernatural: these are the effects of toxic agricultural runoff. The effects, in fact, of a world being brutally poisoned by progress. This deeply creepy novel is eco-horror at its most gruesome and most tragic.

The Vanishing by Tim Krabbé, translated from the Dutch by Sam Garrett

The Vanishing belongs to the same camp of compact and freaky literary realist novels as Ian McEwan’s The Comfort of Strangers—both addictive explorations of people who act in cruel ways simply to see what it feels like. Subsequently adapted into the phenomenal 1988 George Sluizer film of the same name, Tim Krabbé’s second novel is about protagonist Rex’s obsessive, decade-spanning quest to find out what happened to his girlfriend, Saskia, who disappeared during a routine gas-stop during a road trip. Krabbé splits narrative duties between Rex and Raymond who eventually reveals himself to Rex as Saskia’s abductor. In the end, Raymond offers to reveal what happened to Saskia, but on one harrowing condition: that Rex meet the very same fate.

Out by Natsuo Kirino, translated from the Japanese by Stephen Snyder

Natsuo Kirino is one of Japan’s finest contemporary crime and mystery writers, and Out perfectly justifies that epithet. This is a crime novel, make no mistake, but one that presents the bloody actions and reactions of its characters with a cynicism and banality that is bone-chilling. This is a novel about what happens when violence against women becomes a feature of a society and not a bug. With functional prose stripped of any adornment, Kirino crafts not so much a page-turner but a kind of hypnotic drone: impossible to turn off and impossible to ignore.