Sometimes the only way to approach history, particularly a history that has excluded you or one which you felt trapped inside, is to deface it. Defacing—like a form of graffiti—can take the form of literally writing or collaging on top of the record so that your words are visible, but so is the history you are reinscribing. The two interact to create a third space. Similarly, sometimes when going in search of a specific history, you can’t help but research your own. Your history creates another layer to the original, adding to it and permanently altering the way it will be understood or interpreted by others.

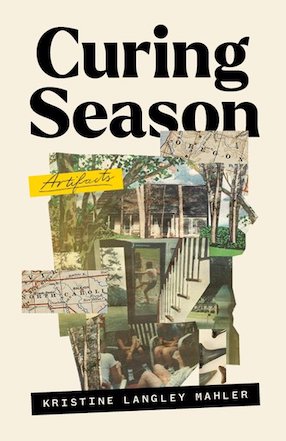

In my debut essay collection, Curing Season, I contend with the history of a county in eastern North Carolina where I moved when I was ten years old and to which I desperately wanted to belong—hello, adolescence!—but I could not find a space for myself. As an adult, obsessed with the county’s book of self-submitted family histories, I approached it as an opportunity to write my own history—on top of theirs.

Nonfiction books leaning against the borders of the genre—which is to say, in that expansive and exciting category called “experimental nonfiction”—continue to illustrate the ways we can work with history while including our own narratives. No one flinches when fiction alters, reshapes, or dismantles historically-agreed-upon narratives. But there are also some incredible experimental nonfiction books doing the work of defacing history, sometimes in a very visceral and visual way, by scratching off the paint, keeping the ghostly outline of what came before, and then making history anew.

The Bear Woman by Karolina Ramqvist, translated by Saskia Vogel

The Bear Woman traces the legend of Marguerite de La Rocque, a 14th-century French noblewoman who was taken to North America and, as punishment for a love affair on the voyage over, abandoned on an island in the St. Lawrence River—a fascinating tale on its own. But Ramqvist’s own motherhood and womanhood are interwoven atop and between Ramqvist’s discoveries (and dead ends) as she combs the brittle archives to learn more about Marguerite, reflecting on how much control a woman has historically not had about the legends of her own life. Ramqvist notes that each person who recorded the details of Marguerite’s story had “their own motives for why they had chosen to tell her story at all, and for how they told it,” acknowledging that she herself must imagine into Marguerite’s narrative as Ramqvist navigates the stormy channel between what is her projection and what is her unveiling of Marguerite’s truth.

A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Gríofa

A Ghost in the Throat also imagines into a legend grounded in history: “The Keen for Art Ó Laoghaire,” a poem written by the 18th century Irish poet Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill about the death of her husband Art. Dubh—who was pregnant at the time of Art’s death and was raising a young family—parallels Doireann Ní Gríofa, who reencounters Dubh’s poem when she is a young mother herself. Ní Gríofa becomes obsessed with discovering more about Eibhlín Dubh’s life, excavating birth records, hospital records, cemeteries and newspapers, trying to find out what became of Dubh. A poet like Dubh, Ní Gríofa seeks history to reconstruct Eibhlín Dubh’s life and finds herself constructing her own.

The Guild of the Infant Saviour by Megan Culhane Galbraith

Megan Culhane Galbraith is an adoptee whose early history was obscured from her for most of her life. The subtitle of The Guild of the Infant Saviour is “An Adopted Child’s Memory Book,” and like memory itself, the book is truth presented with gaps and alterations. Photographs from the author’s childhood are displayed at the ends of chapters alongside images of those photographs which were recreated by the author, using dolls as stand-ins for herself, as well as the inclusion of images stating “permission not granted.” The process of comparing the created and original images mimics the creation of memory, the re-creation of memory, and the reclamation of both fact and memory. Galbraith’s book starts a fascinating conversation about permission, excision, and the shaping of narrative based on what a nonfiction writer must fabricate in her own book to placate others.

Letter to a Future Lover by Ander Monson

Letter to a Future Lover is centered around other peoples’ history. Ander Monson takes the marginalia and tucked-paper-notes left inside found books and writes around what—and who—he finds. A historical trail has been left behind, but Monson makes new meanings from the artifacts through what he himself brings to the marginalia. Is his interpretation accurate? Does it matter? How much respect is one required to give to graffiti, anyway? Letter to a Future Lover is the ultimate history defacer as it both narrates the defacing others have done, but also leaves a layer of its own.

The Witch of Eye by Kathryn Nuernberger

The Witch of Eye turns its gaze on the witches of history and the multiplicity of narratives about their experiences which nearly always drained into one gutter: the official witch trial court transcriptions. Kathryn Nuernberger reminds us that the women’s forced confessions and shouted-down explanations have become the only “historical” records, but in refusing to accept the voice of a predominantly white male justice system as the singular truth, Nuernberger uses her own experiences—along with contemporary court cases—to offer a voice to those women who also longed to deface the historical record but were not permitted to speak.

Evidence of V by Sheila O’Connor

Evidence of V culls together erased-and-partial documentation from the 1930s on the little-known practice of incarcerating teenage girls for the crime of “immorality” so that Sheila O’Connor can imagine into the slim case file kept on record for her grandmother, who was one of those incarcerated girls. I’m obsessed with how flexible O’Connor makes facts, how insistently she reminds the reader that documentation is never complete, how many voices are erased even as they are “recorded” by others. Evidence of V is a wildly exciting addition for the nonfiction/hybrid genre as it blurs facts into recorded fictions and reverses fiction into the closest we can get, sometimes, to facts.

Litany for the Long Moment by Mary-Kim Arnold

Litany for the Long Moment blurs the edges around Mary-Kim Arnold’s adoption from Korea at age two with the twin thumbs of grief and trauma. The memoir is reminiscent of Galbraith’s book as both authors use photographs as a form of evidence to claim facts around their adoptions. Arnold accrues additional sources, like Korean language worksheets and original letters from her social worker, before layering them beside meditations on the work of photographer Francesca Woodman and Korean American artists like Theresa Hak Kyung Cha to question history’s other layer of truth: the one people in diaspora must build for themselves.