“Love is a fire,” Joan Crawford warns us, “but whether it is going to warm your hearth or burn down your house, you can never tell.”

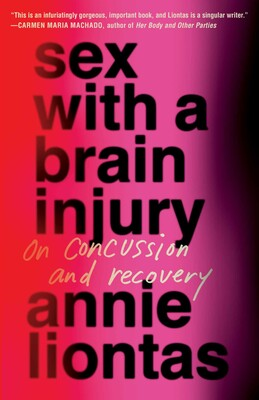

The most dangerous thing we can do—both on the page and in our daily lives—is to take a hard look at how we love, who we give ourselves to, who we are afraid to let in, and why. Any inquiry into the function of love is inherently destabilizing, not only because these relationships are often home, but because they are just as likely essential to our conceptualized self. Writers, take deep dives into the past, but most stay quiet about the present. No one wants to write about their spouse, partner, beloved/s: no one wants to jeopardize what they’ve got. In my memoir Sex with a Brain Injury, I examine my marriage after my wife and I have become strangers to one another, our future together unknown. I interviewed S about the bleakest time in our decades’ long relationship, and we gazed together at what remains. Then I handed S the interview transcript and a black Sharpie and told her she could cross out anything she didn’t want to appear in print. She crossed almost nothing out.

“Love is the whole thing,” says Rumi. “We are only pieces.”

So is love worth it? How do you know? Why do you stay? Is it about need? Sex? Is it February and the edges between you and winter have blurred, and what you want most is to come home to someone who can warm you? Are you simply repeating the patterns you were taught, unable to imagine a freer way of being?

Or maybe she really is your soulmate.

The seven writers below write honestly and openly about intimacy, desire, queerness, loneliness, annihilating marriages, enduring and contradictory love, and, of course, soulmates. Whatever your status, these books might make you feel a little less lonely.

Relationship Status: It’s Over But Only One of Us Knows It

Parakeet by Marie Helene Bertino

The Bride is about to get married to a man who has “familiar, stale bones.” Then her dead grandmother shows up in the form of a parakeet (remarking on how asses like theirs never leave, not even in the afterlife) and starts making demands. “No one can imagine an ambivalent bride,” writes Bertino, at which point, much like the grandmother, she quickly begins to dismantle sacred ideas like marriage, tradition, patriarchy. The Bride says, “Have you ever missed someone so much that the missing gains form, becomes an extra thing welded to you, like a cumbersome limb you must carry?” When she asks this, she is not at all thinking about the groom. Bertino pushes us to consider, If we give ourselves fully to others, what does that leave us with? And how can we more fully give of ourselves? This is an unapologetic surrealist novel, darkly comic, wickedly sharp and full of heart. Wisdom in love, Bertino reminds us, is hard earned, unearthed, precious—like a diamond.

Relationship Status: Soulmates

Above the Salt by Katherine Vaz

This epic love story, which spans from Portugal to the United States (and includes a cameo by Abraham Lincoln) is the antidote to gray skies and winter, and might make falling in love possible again. The novel follows John Alves, the son of a Presbyterian martyr, and Mary Freitas, who is thought to be the illegitimate daughter of royalty. Distance, family, religious differences, gambling, gossip, deceit, mean girls, magic berries. The world tries to keep the lovers apart, but John and Mary find one another time and time again—and then John is summoned to the war between the North and South. Vaz’s writing is as exquisite as warm pastel de nata, those Portuguese egg custards her characters are fed from infancy. The novel is reminiscent of Love in the Time of Cholera in its warmth and mystery, and its belief in epic love—which Vaz, herself, knows a thing or two about. In Above the Salt, Vaz makes the poet’s argument that love is inevitable, sublime and enduring.

Relationship Status: The One That Got Away

The Days of Afrekete by Asali Solomon

The Days of Afrekete opens with a dinner party—mushroom tarts, characters no one would actually want to have to sit next to, a smiling hostess who isn’t feeling especially generous. In the narrative present, Liselle is married to a white lawyer and politician who is being indicted for corruption; at any moment, the FBI might arrive and break up the party. At its heart, Solomon’s novel—inspired by Mrs. Dalloway, Sula, and Audre Lorde’s Zami—follows the searing, tempestuous affair between Liselle and Selena, two young Black women who grew up in Philadelphia. Theirs is a complicated love, a buried love, but one that refuses to be forgotten. And yet Liselle tries very hard to forget (so hard, in fact, that we wonder if Liselle is the one who got away—from herself). The Days of Afrekete is a novel that celebrates queer blackness while interrogating the necessity/cost of choosing security and comfort over selfhood. Solomon is mischievous, sly at dialogue, the friend you go to for tea. A novel as sexy as it is heartbreaking.

Relationship Status: Separated

Rainbow Rainbow by Lydia Conklin

This award-winning story collection is about queer desire and what gets in the way. Rainbow Rainbow is written from the perspective of outliers, lusty teens, hot breath, engendered embodiment, surviving the homophobic ’90s. It is fleshy, quaking, at times as startling as a sudden wave of attraction. In “Pink Knives,” a nonbinary narrator about to get top surgery begins an open-relationship affair during Covid and allows a stranger to remove their binder, something they denied their girlfriend. In “Ooh, the Suburbs,” Heidi pushes her friend to meet up with an older woman to play out her own complicated impulses. A group of friends flash cars from an overpass, someone secretly masturbates in class. In step with these nonbinary and trans characters, the reader senses there is always potential threat and implied trauma. Conklin, incisive and watchful, resists the convenient cultural narratives that flatten or homogenize the queer experience, and still celebrates queer joy.

I once asked Conklin, if Rainbow Rainbow were a bar, what would the vibe be?

They replied, “Funny and a little unhinged and fun. People dressed in strange bright outfits, kind of joking and laughing. But then in the corner someone would be silently crying.”

Relationship Status: It’s Complicated—Really, Really Complicated

Rien Ne Va Plus by Margarita Karapanou

Halfway through Rien na va Plus, Karapanou writes, “Every time I want to write, I want to write love stories. But as soon as I pick up the pen I’m overcome by horror.” This is a genre-bending love story about marriage and narrative unreliability, told from two points of view: the self in darkness and the self in light. A man and woman marry, but it ends badly, in cruelty and infidelity. There are strange allegations, sharp words, troubling silences. The wife, Louisa—if that is even her name—tells her version of events in the first half of the book, relaying how controlling and devious her husband Alkiviadis is. Then she tells the story again, giving us an entirely different Alkiviadis, an entirely different her. The falsehoods mean Louisa gets to protect a small part of her freedom, even as she is bound to another. Karapanou, born in Athens in 1946 to the daughter of Greek novelist Margarita Liberak, saw herself as writing outside of national boundaries. Her first novel Kassandra and the Wolf was published during the Greek dictatorship between 1967 and 1974. Even—especially—when Karapanou is writing about intimacy, she is writing about escape, evasion, willingness, culpability. She has been compared to Marguerite Duras, Ingeborg Bachmann, Mary Gaitskill. The Greek novelist Amanda Michalopoulou says of Karapanou, If she had been American, everyone would know her.

Relationship Status: Open Source

Sula by Toni Morrison

Whenever I return to this perfect novel, I read it as a love letter.

Nell and Sula, two Black girls growing up in Bottom, Ohio, are best friends; as adults, they become estranged when Sula sleeps with Nell’s husband. But this story is not about men, it is about Black women’s desire and the intimacy possible when women refuse to be restrained by heteropatriarchy. Toni Morrison, in talking about her second novel, insists that “Female freedom always means sexual freedom…the only possible triumph is that of the imagination.” Nell, who comes from a quiet, confining home, ultimately rejects prescribed roles of matrimony and family; Sula, who is raised by a one-legged woman who it’s rumored let a train sever her leg to collect on insurance, won’t prescribe to Bottom’s rules about sex—but when she goes looking for love she realizes that she’s not going to find it in men. Sula, told to get married and have a baby, replies, “I don’t want to make somebody else. I want to make myself.”

Morrison’s language is sensual, smoldering—erotic for all of the possibility that exists between two Black women who refuse to play by unfair rules. The friendship between the two women is marked by “unspeakable restlessness and agitation,” with scenes of intimacy as provocative as an Alice Munro story. This is a novel that understands that Black queerness is about living authentically at the margins, on one’s own terms.

Relationship Status: “I am yours. I am still I.”

Human Dark with Sugar by Brenda Shaughnessy

Sexy, dark, funny—everything you could want. No other poetry collection is as hot to the touch as Human Dark with Sugar. Shaughnessy’s celebrated second collection is addressed to the beloved. Restless, demanding attention, toying, longing, (“Oh, to be ready for it, unfucked, ever-fucked”), refusing to ask if you’ll stay but hoping you’ll still be here in the morning.

“To play without shame. To be a woman

who feels only the pleasure of being used

and who reanimates the user’s

anguished release in a land

for the future to relish, to buy

new tights for, to parade in fishboats.”

Titles like “I’ll go anywhere to Leave You But Come with Me,” “Replaceable Until You’re Not,” and “I’m Perfect at Feelings” tell us everything we need to know. And then, there’s “One Love Story, Eight Takes.”

“To see you again,” asks Shaughnessy—“isn’t love revision?”